In 2015 when I was still in high school, I began doing this community engagement work, bridging resources for creative education for Black and Brown folks. I interrogated disconnection and loss, starting with myself, recognizing my own feelings of loneliness. I asked, why is my head spinning so much? Why do I feel this urge to be on my phone when there’s nothing there? As I unpacked what I was experiencing, I had conversations amongst my peers, and recognized that my experience was common.

— Philli Irvin

Creator of ITS: A Creative Ecosystem for Young North Minneapolis Artists

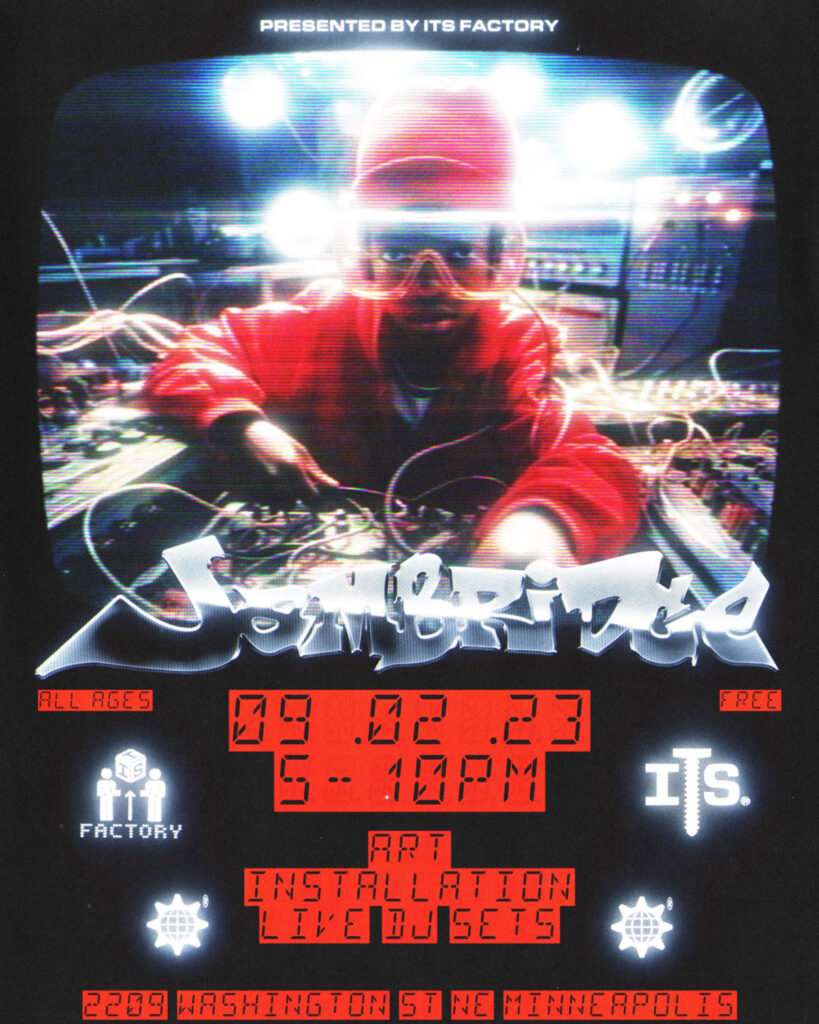

ITS is a two-part creative ecosystem designed to provide resources, funding, and space for early-career Black and Brown artists to thrive. We have done annual productions since 2016, with the exception of 2020. In 2023 our project was called JAMBRIDGE. We remembered Miami Black and Brown creative youth movements of the 1980s: the era of drum and bass and booty shaking music. JAMBRIDGE took place underneath a bridge on Washington Avenue NE Minneapolis, between 23rd and 24th Streets.

Inheriting a Creative Spirit

My grandparents hold this creative spirit. They come from Tulsa, Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, and Oakland, California. My dad was born in Chicago in 1970. His mom moved to Minneapolis when he was in high school. My mom’s mom was born here. I was born in 1997 and grew up on 18th and Lyndale in North Minneapolis, on a cute lil cul-de-sac — the same house that my mom grew up in. My parents still live there, and I live there sometimes too, even now.

Relationships—expressed in different ways—were really important in my family. We did a lot of intentional gathering and bonding. We would go to the apple orchard, Mississippi Regional Park, the State Fair. My great grandma would make quilts. Growing up, I saw a lot of arts and crafts. My grandma would have these different craft projects. We would make African pancakes. She would have us put beads in this flat plastic thing with thin spikes that look like tips of a pen, put wax paper over parchment paper and then iron it, to make pixelated stickers.

Harvest Best Academy: Afrocentric Education

I went to Harvest Best Academy from pre-kindergarten to 8th grade, with the same group of kids all those years. We had to wear suits and ties. The days were long—we were there until 5 or 6pm—and we had school year-round. As a kid I hated those long school days, but I have a different perspective on it now, realizing how much they taught me. It was a really beautiful experience that I’m grateful for.

The academics were rigorous, which made high school easier for me. Our reading, writing and math levels exceeded standards. We were tested every Friday. I finished algebra 1 and 2 in middle school, so high school was pretty smooth.

It was an all-Black school that was really intentional about making sure we understood our heritage and had a relationship to family and lineage. The curriculum was Afro-centric. Every morning we gathered in the gym for a ceremony that now I recognize as acknowledging and honoring ourselves, our peers, our elders, and our ancestors. We would sing the Black national anthem. We would start the day off with a creed: “Who’s the best? We’re the best!” A lot of affirmations.

In my middle school we did this cultural programming. Every classroom would become a different place in Africa, and we would learn the culture, the food, the languages. We would all take turns presenting and then visit each class. It was really fun. I didn’t realize it then, but a good amount of the staff was from West Africa and a good number were Muslim. I remember them going somewhere during lunch to pray.

Spirituality

I grew up Christian. My mom’s dad was a pastor at a church in Saint Paul. When I was young the practice of Christianity scared me. I’m still unpacking and dealing with that fear of being wrong or doing the wrong thing. It did create this consciousness about my actions, being aware of the harm I’m causing. But when I was little, I wouldn’t be able to sleep thinking about it. It was just confusing and scary. I was watching this Octavia Butler interview and she spoke on that theme. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve started to build my own relationship with God. My mom comes from the sort of philosophy of “God is love.” My dad is Christian as well, but neither parent forced it onto us. We went to church, but when we got older, they encouraged us to have some sort of personal relationship with god. Right now, I’m trying to separate what I actually believe is God or love and what is fear, what is capitalism, or other outside noise. I think the piece that I started to learn is that love is energy. And that’s how I recognize it.

Youthful Endeavors

I was really into drawing as a child, but I was also very outdoorsy. My grandparents lived in Springfield, Illinois, for a bit of time, so I got to be around hay fields and tall grass. We went fishing. I attribute my interest in drawing to my cousins Ej and Hakeem. One of them showed me how to draw a vampire in like third grade.

I loved this show called The Kids Next Door, about kids who have the best communication system. They’re globally connected and battle adulthood in different ways. I was also into Dexter’s Laboratory and Toonami, cool futuristic cartoons and video games that I grew up watching and playing.

Hopkins High School

My parents wanted me to go to North High school, where they went. Somehow, I knew that Hopkins had Adobe software (Photoshop in particular) and I knew North didn’t have those things, so I insisted on going to Hopkins. It was my first time around white people. In my senior year there was this ceremony where students were given different awards, like, “most likely to be a millionaire.” Only one Black person got an award. In response I produced my own senior video on the experience of Black and Brown students at Hopkins. I did interviews and pieced together this four-part documentary.

At Hopkins I didn’t like the basis for how students treated each other. It didn’t seem like they cared for each other beyond the surface. I am not sure how to put it. I don’t have great connections or memories of teachers either. There were exceptions. Mr.Terrell, one of the Black staff, always looked out for me and showed love. And my math teacher, Champ. I don’t think I had a class with her, but Ms. Heimlich was pretty tight.

I don’t think the uncaring atmosphere was necessarily about the individual teachers or students. It was just the culture. When you’re in a space and the culture—the standard of what is acceptable—is uncaring, then, whether you’re aligned with it or not, whether you’re perpetuating these things intentionally or not, it still creates an unfriendly environment. That environment was especially strange to me.

Still, I’m grateful I went. I did end up learning Photoshop. There was this event a few of my peers at Hopkins threw called Buckfest (2014). Asher, Alex, Drew, Francisco, and Dakota. I don’t know if I ever told them but that inspired me to do ITS FEST. So in all, I was able to play around and learn things that are integral to my artistic work and community engagement now. Super grateful for that.

I had a few good friends at Hopkins I’m still connected with: Namir Fearce, Sydney Baird-Holmes, Siona Fitzhugh, Arandas Johnson, and Bianca Williams. We grew up in performing arts. To us, activism was integral to the arts. We did protests and stuff throughout the years. I used to wear this bear mask that I got in Chicago on a college tour. I would kind of be like a hype man for performances and host events too.

Extracurriculars

I grew up going to a lot of camps and extracurricular activities. My parents, especially my dad, were not going to let me sit around in the summertime. I went to entrepreneur camp my junior year of high school. I was in Journey Productions which is a Black-lead production company that centers around heritage. The Sankofa bird’s journey is the inspiration. It was created by Tonya Williams. She and her spouse Jeremy Williams, Cyreta Howard Oduniyi, and Calvin Turner were big influences in my life during high school. Mr. Ed at Oak Parks FAN program introduced me to video production. Those experiences were important to me, bridging the relationship between community and creativity.

Becoming A Community Artist

High school is when I began doing this community engagement work, bridging resources for creative education for Black and Brown folks. I interrogated disconnection and loss, starting with myself, recognizing my own feelings of loneliness. I asked, why is my head spinning so much? Why do I feel this urge to be on my phone when there’s nothing there? As I unpacked what I was experiencing, I had conversations amongst my peers, and recognized that my experience was common. There was this desperation, this desire to connect. I also realized a lot of people hadn’t had the fortune of consistent healthy relationships, in terms of being a mutual exchange; I care for you; you care for me. I was interested in the things we do to connect and deepen our relationships, not just occupy space.

As I was asking these questions, I was also being introduced to Youthprise. My friend Namir Fearce was like, “Hey you should apply to this fellowship.” In my Youthprise interview video, I described this vision of Minneapolis as a cultural center for arts and how I wanted to be part of bringing that vision to reality. My vision was not just of physical space but also of programming, recognizing that we don’t necessarily need to go through certain institutions to realize ideas and bring resources and people together. Sometimes—oftentimes—those institutions have their own agenda whether they know it or not. I think it’s valuable to understand that people come with their own ideas. Why not help foster them?

I came to the project with both artistic, activist, and entrepreneurial experience. Harvest Prep/Best Academy had us reading books like Outliers in Middle School. Junior Entrepreneurs of Minnesota and U of M account camp for teens taught me about building a business plan and crunching the numbers. Youthprise introduced me to the basics of aligning purpose vision and language, and they also did a beautiful job of integrating humanities and alternative strategies; tangible tools for developing your vision and actionable steps.

I was processing my experience through writing, through questions and through larger conversations, noticing intersections and asking, how can we support each other? When it comes to emotional experiences, I think sometimes problem- solving is not about eradicating the problem (the feeling), but managing it. How do we manage this isolation, this fear, this disconnection? Young folks have visions and voices. How do we provide resources to grow them? There are steps in between, is what I am trying to say.

First Collaborative Event

In 2015, while me and Namir Fearce were transitioning out of high school, we did our first collaborative event called Kids Next Door inspired by the KND cartoon. The concept was: link and get lit; connect and celebrate. At the time there weren’t many spaces for young teens to gather in a creative and performance way, especially Black kids. They had these teen clubs, but it was more like teen adult partying versus like teen creative exchange. We put together a performance, did the promotional stuff. That was our MVP— minimum viable product, or prototype.

Youthprise Fellowship Lessons

Youthprise Change Fellowship taught me how to talk about my vision and how to center my values in that vision. Sometimes I’ve had ideas and people say, “what are you actually talking about” and I’m not able to answer. It’s recognizing the difference between having an idea versus having a relationship with an idea that you can articulate. Youthprise gave me the funds to do more digging, to realize the idea. It was a yearlong program. We had regular meetings with mentors: Libby Rau, Neese Parker, Wokie Weah, Bianca Dawkins, Jake Heinz. And they had really good food. I didn’t even know they made food like this in Minneapolis. I was still a teenager, getting paid a stipend to learn. I think over the course of our program they gave us like $11,000 which for a teenager is a lot. It was amazing. There was a portion for the learning session, a portion for our actual ideas. We need to have those experiences to learn what you do with the money, what’s a lot of money. It helped me grow my relationship to money, to planning and budgeting.

First ITS production, 2016

The first ITS event I did was in 2016, the summer after my first year at Columbia College in Chicago. I was standing by the Panera Bread on State Street in downtown Chicago, close to the Harold Washington Library, and I thought, ITS!

At first it was an acronym: Intro To Summer. I thought the event at the end of the summer would be OTS Outro To Summer, which didn’t sound too good. There was a phrase going around: “OTS, Off The Shits,” which was associated with being under the influence of some sort of drug. I didn’t want to be associated with that, so it was Intro To Summer, which is why we carried it out in June that first year.

While I’m in Chicago, my now brother-in-law Julius Johnson was meeting with potential venues. He was my person on the ground in Minnesota. I’m in Chicago, it’s my first year in school and I’m organizing this event in Minnesota. I’m studying video production, learning a lot. My sophomore year I switched to illustration. The course, Introduction to Visual Culture, gave me practical tools for unpacking what you’re seeing, which starts with observational skills, writing what you see, the connotation & denotations and then diving deeper. All those things I’m carrying into my community programming.

Working with this gallery downtown revealed the troubles of being a young creative. Regardless of age, if you don’t have the information, you’re in the position to get finessed. As we got closer to the event the gallery owner started to change our terms, raising the price, limiting the space. We ended up just being in this side gallery space and paying twice what we agreed upon. I learned we have to protect ourselves. It still turned out to be a beautiful experience. It was like a good turnout; about 60 people.

Evolution of ITS: 2017 – 2023

Afterward we continued to evolve. We did ITS Home. Home is where the heart is. At that time, I was reading A Frame for Life. by Ilse Crawford, interior designer with a philosophy that puts humans at the center of design; thinking about how do you cultivate and acknowledge the needs of people in a space? I was picking up these design principles, psychological and sociological practices and ways of thinking about space and quality of life.

ITS has been an annual thing since 2016, though we didn’t do programming in 2020 because of COVID and the Uprising. The first few years we focused on basic questions: how do we gather in meaningful ways and build community? How do we build leadership and delegate? How do we realize ideas at a larger scale? How do we get partners and sponsors? I remember I was afraid to send emails. I was learning in real time, how to work with bigger organizations, like First Avenue, the Lowry Business Association and New Rules.

Mentors

I can’t speak on the work we’re doing now without talking about mentors Christopher Webly, founder of New Rules, and Leslie Redmond. Leslie was at the very first ITS FEST and connected me with Chris. She is like a big sister and has loved, guided, and supported me since the beginning. Leslie connected me to one of the most life changing grants from the MN Black Collective Foundation, Black Led Change.

Chris connected ITS to the resources as well, taught us how to pitch ideas, gave us a lot of tangible skills. At first, we were just running on energy. In 2018 we had a budget of like $2000. From there we went to a $15,000 budget because of the resources that Chris brought us. Chris is not from here but still a Northside soldier. He’s someone who really showed me what it looks like to have a business but still care, that it’s unacceptable to treat people inhumanely.

When me and my group of friends; our creative circle, needed food or a place to stay, we could go to New Rules. I would go there and draw when I needed some silence. I’m Black, I was 20 and my other friends were even younger. Chris opened the place and gave us the keys. That kind of trust is unprecedented. That level of trust enabled us to go from $2000 to $15,000. I went from being able to pay 10 people to 20 people: the creative team, the performers.

In the summer of 2018 my friends Papa Mbye, Tyler Jackson, Murad Sayf, and I did this show called Work in Progress. We met with Tricia Heuring from Public Functionary and talked to her about the idea and she was down. We occupied the space for 48 hours. We had people bring us food. We had a live stream going even while we slept and brushed our teeth. The space evolved each day. During another three-day period people came in and out of the space. Each day there would be work. We did some interior installation stuff.

By the end of the show, we had this whole body of work, this live stream, and a conversation which is still available on YouTube. It’s moments like that where people are vulnerable enough to open up their resources and really trust you, that amazing things happen.

2020

In 2020 I was like, man! I don’t have to do a festival! I don’t have to be a college student and produce a festival. I was allowed to just be a person, a non-artist. I had family time. I was also in a relationship.

During that pandemic and uprising year, questions arose for me about what is really important, what matters, how quickly things can change, how I see myself when it isn’t in context of the things that I was doing or making. In a way it was a blow to my ego.. I’m not making anything, so where’s my value? Where’s my esteem coming from? I started to recognize that I have to love myself outside of what I do. When you express yourself in a manner that associates your identity solely with the work you do, you inadvertently reinforce this habit in your mind and body, tying your self-worth and identity to that singular aspect.

In the United States “What do you do?” is a go-to icebreaker. Followed by “I am a…”. I am curious about whether that aligns or not. How else does that impact how we move through the world and what’s nurturing our spirit, what’s loving, what’s caring?

I did a lot of biking, reading, and writing. I read bell hooks for the first time: All About Love and Communion: The Female Search for Love. I was unpacking my relationship. I didn’t realize I was dealing with a lot of codependency and anxiety too.

Healing from Trauma

Back in 2017, l smoked weed laced with something hallucinogenic, and I didn’t know it. I had this psychotic break where my understanding of reality was obliterated. I realized, oh, this is what people mean when they say anxiety attack. I couldn’t sleep, couldn’t eat. I was in this weird limbo, questioning reality. I was terrified of my shadow. It was hard for me to walk from class to my dorm room because there were lights and there’d be shadow. I was super paranoid.

I read this book on anxiety. I was terrified to express so many things to my parents because of my upbringing, self-image, and Christianity. I thought I had to keep what was going on between me and God, or that I had to deal with on my own. It was a spiritual kind of battle I was going through in 2017, that ultimately helped me to open up a lot. I would hope no one has to go through that to open up, but that’s what got me here. It helped me begin to recognize my need for honest transparent conversations, the responsibility aspects of love, recognizing that I need to care for myself and other people. So that continued into 2020. During the pandemic I was shedding a lot of those boxes, recognizing that I am, and we are, much more than the things we call ourselves.

I have this quote I say to myself: “I am, is a metaphor.”

Social media is where we engage in behaviors we might not align with philosophically, yet we practice them over and over. My friend Aria Gilliam says repetition is the mother of learning. It reminds me we are constantly physically and spiritually practicing what we might not believe in.

Terror and the Uprising

The Minneapolis Uprising of 2020 was terrifying in many ways. My partner stayed north of Uptown. I remember being at her house one time and she wasn’t home yet. I walked up the balcony stairs and was sitting in the back, and I saw these guys. They had these weird racist sculptures in the garden. They were biker gang types. I overheard them having this meeting. They were talking about “Ground Zero” and using war terminology. I was scared af. I looked down and they were coming out of the neighbors shed and one guy looked up and stared me in my eyes. I froze. I am not sure if he saw me because it was dark outside, but he started coming up the stairs. It was like one of those dinosaur movies. He came up one more flight. And then he stopped and went back down.

Oh my God, it was terrifying, being that close to the chaos and seeing how quickly you can go from thinking you’re safe to all of a sudden, the Hell’s Angels are right around the corner. I wonder if that connects to why I feel this heightened sense of paranoia. I feel like I’m in danger or like it’s hard to shake that thought of checking my surroundings.

The Beauty of the Uprising

I spoke of the terror of the uprising, but I also have to speak of the beauty of it.

I am extremely grateful because I experienced what global unity would be like. There was a good span of time where I could go anywhere and I could get food, I could get water, I could get toiletries, anything I needed. I was like, “Oh my God, amidst the chaos I am experiencing World Peace! We can actually come together.” Because of that experience, people can’t tell me it’s not possible. I was able to see that exchange of resources, how we went beyond the boundaries of what technically you can or can’t do. We surpassed ourselves, transcended those rules—like the rule that you can’t give this young kid the keys to your establishment.

Recently one of my peers, Cat Grimm, shared a writing with me and we talked about this idea of needs in loving relationships in a “I need you and you need me” type of way. It reminded me that we don’t often express that we need each other. During the Uprising we allowed ourselves to need each other. It was amazing.

Leaving the U.S. to Unlearn and Relearn

After going through the pandemic, a breakup, and a civil war, I felt like life is short, and I needed some space. I wanted to see the world and distance myself from the American behaviors I’d downloaded. I figured if I went into a place that didn’t practice these behaviors, I could see what it is that I was repeating even unconsciously, that was not loving, caring, nurturing, mutual. I wanted to be conscious of how I moved in relationship to people, to space, so I could act on the values I aligned with. I left the country to unlearn and relearn.

I initially was going to go to Australia because two of my friends—Chango Cummings who was studying architecture there, and Fredrick Edwards who had visited—told me that they don’t have that sort of scarcity mindset there. They wanted me to experience that. But then Australia was closed due to the pandemic, so I couldn’t go.

So, I went to Mexico City. I didn’t know how bad my Spanish was. I had a little Spanish in high school. I really couldn’t speak. The first three weeks I was there by myself, and I didn’t know how to get any of the things that I needed. I didn’t know where anything was. I was dying from thirst. I would go to Circle K because it looked familiar, to get water. I realized I could barely function because of my lack of Spanish. I couldn’t read or understand what anyone was saying. I ordered food on Rappi which is like Uber Eats and stayed in because I was afraid to socialize or be put in a position where I had to express my ignorance of the language. But eventually I made friends. People were really helpful. I felt supported. I met artists and non-artists. The social temperature was different, literally warmer.

How We Got to Now

I was reading this book by Steven Johnson called How We Got to Now: Six Innovations that made the Modern World. I picked it up because it was written by Steven Johnson which is my birth name. I could talk all day about it. The book talks about how the convention of time is fairly new. Before 1883 time varied by in cities as close as Minneapolis and St. Paul. Today we “spend time” or “waste time.” We have downloaded a way of communicating and thinking about time. But that can change. A lot of what we think of as conventional and timeless, is actually less than a century old, some less than 50-60 years old. We’re experiencing so many new things at a massive scale.

Johnson has this chapter on glass. Glass was discovered in the Sahara desert, a natural element created by the sun and heat. It found its way into the trade market as an ornament. You jump in time and space to these Turkish blowers who took glass from being something cute to something functional. They were exiled to an island because they were burning down the town. Still, the townspeople realized what they were doing was economically beneficial, so they created this culture around glass blowing. They had this concentrated environment and ecosystem of working with the glass which led to the advent of silicon dioxide aka the transparent glass we know now. Today glass is the thread that ties us all together: the Internet, the World Wide Web, our phones.

In college they force you to think about the internet when what you need to do is play with heat and sand.

Maybe we don’t have to be so focused on what it is that we’re creating and just trust that there will be a need that arises and there will be a process that’s developed through just playing and exchanging with each other.

I think about those Turkish glass blowers and the unity that I experienced in 2020. I think we find genius in a collective expression of needs and a sharing of resources that allows us to come together and do something that is beneficial for all of us. We don’t have to do that in a manner that is oppressive and causing harm.

Johnson’s ideas shattered everything for me. I love being fractured like that. It makes room for something new.

“What Does to Mean to Make Art that is Self-Sustaining?”

What does it mean to be self-sustaining and not always have to think about money? It’s taking so much money to create and to do this programming and I need to be compensated. I would literally die if I continued going down this path. Now we are focused more on how we realize larger scale ideas and how we build things that are visually appealing and functional, bridging arts and technology.

We also need utilitarian sort of skills where we can not only make beautiful murals but also provide for ourselves as a creative community. How do we work with the resources—because if you don’t know how to work with the resources you have to rely on someone who does. I need to know how my phone works, or I need to know how to communicate with or without these systems: build without Home Depot. That’s what we were thinking about in 2021 when we did ITS Factory where we conceived this idea for a creative educational residency as a third pillar of our program: community engagement, creative education, and fabrication.

After the pandemic and reflecting on the impact on my mental health caused by my festival cycle, I realized I need to take a break and refocus; maybe scale down, work on a more sustainable business model. I decided to just do a few, what we call, level one projects. A level one project requires minimal resources to execute.

So now we’re taking a step back from programming. We’re not doing as many things. The resources still have to come from somewhere so where are they coming from and how do we sustain? I’m taking the time to self-reflect and then also work with mentors and team to come up with solutions. That was part of the shedding and cracking that I had to go through. I think I started to demonize anything that my principles or values didn’t align with being carried out. I still have to learn what things are useful. I don’t have to reinvent the wheel. So, with all those thoughts and philosophies and spirit and value coming together, in 2023 we’re doing two or three events, but simpler.

JAMBRIDGE: a Focus on Heritage and Lineage

With our 2023 production JAMBRIDGE, we remembered a place and time. We focused on Miami in the 1980s but I was also thinking about that bass element I found in Chicago, Mexico City, and New York. We were interested in seeing what was behind that bass; what are the things that we carried forward that we might not acknowledge; how we create that path to remembering. Our big challenge this year—or opportunity—was to learn how to utilize what we know as performance and DJing to tell a cohesive story. How do you get people to understand or bridge relationships in a short amount of time. It’s not like we’re watching a film. We’re not looking at a flat surface. We wanted to bring that ethos to life. We integrated ceremony with sound; not parts and pieces but a body, all living together.

So many things that are not concrete are invaluable—you can’t even hold sound.

Remembering is important. There are people who came before us who did that work, and we have to pay respect. If we don’t, we also lose something: solutions, ways of being. We talk about disconnection, and people feeling isolated. We know that in the past people have had practices of gathering and coming together. If we don’t honor those, we lose the opportunity to connect to those things.

A lot of things we think are erased still have a presence. How do you recognize the value in what is left? That’s a big question. JAMBRIDGE focused on heritage and lineage. It is thinking about memory. How do we remember what is important and how do we carry forward?