The name of my organization—Black On Black Development and Entertainment, Inc.—confronts the fact that most of the time “Black on Black” is paralleled with a negative. I wanted to let my people understand that we need to control the narrative. Many times, I was told the name was a character flaw for the organization; it was too abrasive. Even people I admired and wanted on my board didn’t want to sign on because of the name. But I had to remain true to myself. It was one thing being in corporate America and not getting the accolades and respect that I deserved. I refused to water down something that I created with my own blood, sweat, and tears.

— Angela Hooks

Oklahoma Rodeo Queen Girl

I turned 53 on September 24th. I was born in a very small town in southeast Oklahoma called Idabel. At heart I’m really a southern belle. I’m still the little girl that wanted to be a rodeo queen.

My parents decided they were moving to Minnesota when I was four. I remained with my grandmother for two more years. At the age of six my parents said, we want her to have a more cultured, citified, prosperous education and life and so we are taking her to Minnesota, now that she is school age.

Minnesota Culture Shock

Coming to St. Paul at age six was a complete culture shock. Until then, I had no idea what it meant to be a minority. Don’t get me wrong; I knew white people in Oklahoma, but they lived on the other side of the tracks. The ones that went to school with me were poor; they lived on our side of the tracks, and they were the minority. So, coming to the Twin Cities I was thrown into a situation that was drastically different. I look back on it now and realize I was traumatized. I didn’t have a choice. I had to adapt. I made sure to make good grades and not complain—even though I was experiencing things that really affected my makeup—so that when summer came, my parents would let me return to Oklahoma, and to my grandmother.

In Minnesota I remember my only white friend asking me if she could touch my hair, and all the other questions that come along with that: “why is it like cotton?” I replied, “because I’m Black, and it’s normal.” I did think I was normal. I thought she was dumb. I was raised with such confidence, by all these strong women, that I didn’t even feel offended. I thought she was just naive, and I wanted to educate her. But those kinds of questions continued all the way to high school. At some point I realized that everybody is not naive about Black people, they were out of touch. There needs to be a connection and some education, and that’s why, years later, I formed Black On Black Development and Entertainment, Inc. the nonprofit I now work for.

I loved riding horses and I wanted to be a rodeo queen, but I was forced to move to the city.

When I entered junior high, I started to develop into a young lady and my parents were like, No more going to grandma’s all summer without us keeping an eye on you. So that stopped. It was saddening, but at the same time, I found another outlet for my rodeo queen desires.

Performing Life Began While Home Alone

When I first came to Minnesota, I lived in Rondo, in the Summit and University area. Then I moved to East Saint Paul, to the McDonough projects. When my parents divorced, my mother was a single woman in the projects. My father remarried a white woman and still lived in Rondo. When my mother remarried, we moved to Roseville to the suburbs. She did not want me to deal with the challenges of the inner city. She wanted me to be able to focus on my education; to have a better life.

Well, I got that, because of the closeness I had with my mother. I was a latchkey kid. We couldn’t afford daycare, so I was trained to get myself onto the school bus and let myself into the house after school. My mother was going to college at night. Being the only child at the time, I had to be responsible, accountable, and independent. And because I was home alone a lot I would go into a fantasy world. Many people know me as an entertainer, a performer, a singer, and an actress. My performing began when I was alone at home.

I have always viewed my life from a lens of very strong Black women. I didn’t have a lot of male contact as a young girl. My grandpa, my uncles, and even my father were sporadic. They loved me very much, but their presence was not consistent. It was more visited or arranged. So, I have never thought that women couldn’t do what men do, because I watched all the women in my family do what we needed to maintain us.

Performing in Church

When I moved out to Roseville, my godmother would pick me up on Sunday and take me to Pilgrim Baptist Church on Central Avenue in St. Paul. I joined the youth choir. We had rehearsals every Saturday and performances every other Sunday. I began to get solo parts. People took notice. I’m twelve-years-old and I’m standing out.

I didn’t know that Pilgrim Baptist was a prominent church for Black Minnesotans. NAACP presidents and Black school principals and school board members went there. The pastor approached my godmother, saying, “Wow, she’s incredible. Not just as a vocalist but she’s photogenic. She has personality. My wife runs a teen pageant and we’ve got to get her in there. She’s our next winner.”

My godmother said, “Well, you got to talk to her parents about it.”

Pastor Earl F. Miller, Sr. and his wife Eunice went out of their way to come and talk to my mother and stepfather. They said “Listen: I don’t know if you know what you have here, but we’d like to groom her as our next queen for this pageant, to represent the state of Minnesota.”

Teen Beauty Queen

I began rehearsing with the pastor’s daughter, who had won a national pageant years prior. She and her mom coached me. At the time, I was a little twelve-year old with pigtails and glasses. The first thing they did was give me this duckling-to-swan transformation with contact lenses. It was the first time I learned how contact lenses worked.

I go to the local pageant. I win. I go to Dallas, Texas, to represent Minnesota. I win. So now I have to go to Antigua to the Miss Black Teenage World pageant. I am fifteen years old. I go to Antigua. I win. So now I’m this Miss Black Teen World and I am traveling the world speaking to black youth about the importance of education, and not doing drugs, and being confident and empowering yourself.

At home, in between traveling and school, classmates in Roseville were like, “Oh that pageant? It doesn’t count. Who cares? It’s not Miss Teen USA.”

Focus on College

My focus was to get a scholarship and go to law school. I received a scholarship through the pageant for the historically Black Hampton University. I was quoted in an interview in the Roseville Sun saying I wanted to go to law school after Hampton. The Roseville Gavel Association which honors lawyers and judges, saw this article and decided to give me an honorary award that year to fund law school after leaving Hampton. I was the first young person and the Black person to ever receive that award.

At the time, I was getting ridiculed by my homeboys and homegirls: my cousins and everyone in the hood. I always spent time with family and friends in the Rondo area or the projects, even though I lived in Roseville, and I got teased. They called me Oreo, and said “Now you forgot about us” and “You’re so articulate you don’t talk fly anymore.” I was really in a tug-of-war.

Of course, I wanted to honor my Blackness. I was approached to run for Miss Minnesota. It was right after the whole Vanessa Williams situation. They said: “Someone has to clean that up and represent real Blackness. You are that, Angela. We need a well-bred Black woman to go represent us.” This is the pressure I was getting, but I decided to run for Miss Black Minnesota instead.

I was first runner-up, though I won four out of five of the categories. The queen was a Gopher basketball player. That is when I learned about the political aspects of pageantries. You find out at age nineteen that the world is not fair.

University of Minnesota

I decided, I don’t need Hampton University. I just want a good education. I’m Black and I know I’m Black. I don’t need a college to tell me that. I pursued a scholarship at the University of Minnesota. The College of Liberal Arts did give me one, although halfway through, they reduced it to a partial and I had to go to work. I was there from 1988 to 1991 before the scholarship was cut. What should have been a ‘91 graduation, didn’t happen until 1994.

To make ends meet during those college years, I started singing in commercial jingles, touring with major artists as a backup singer, and taking on musicals at local theaters. In between school and my performances, I landed a job at the Ordway Theater as an assistant to the development director.

Corporate Systemic Racism at the Ordway

At the Ordway, I had my first experience with corporate systemic racism. I was not getting the duties, responsibilities, and education described in the job. They tied me to my desk when I should have been with the rest of the staff, mingling with the President of Disney, for example.

When I complained, they began a campaign to get rid of me for speaking up for myself and expecting what should have been given to me. Because this work correlated to both my career aspirations in music, entertainment, and business, I was not giving up without a fight.

The last straw was when the receptionist called me the N word. I was told I would really hurt the organization if I went to the NAACP with a discrimination complaint. The president called me into the office to explain to me how much it would hinder Ordway’s goals and my future if that were to get out. I just wanted to be accepted and respected as a team player and so I rolled with that. I never went to the Human Rights Department or the NAACP. I never filed any a lawsuit. None of that. Three weeks later, I was terminated, and they contested my unemployment. I realized I’d been bamboozled.

New York, New York

Despite the racism I experienced at the Ordway, I was bitten by the show bug. I packed up what I could fit in my car and drove to New York. I said I wanted to be where it’s a melting pot: where color doesn’t matter, where culture doesn’t matter, where you are going to get your just deserts because of your skills. I didn’t know a soul, didn’t have an address. I slept in my car for about three days until I learned about hostels. I lived in a hostel until I registered with some talent agencies and temp agencies. Soon I was working corporate and auditioning for roles.

I loved it. I went to a job interview and all I saw was Black: people wearing dreadlocks and French braids. I thought, “Oh my God I’ve just I’ve missed out so much! They were even telling me, “Kill the sweater. That’s way too Minnesotan for us. You got to get more savvy here.” I’m like wow, this is great.

Except when I went home to visit. I had such amazing mentors growing up — the Millers, Arlene Van my dance teacher, and those who introduced me to community service and advocacy like Jim Robinson, Lou Wiley, and Bobby Hickman. When I’m back in Minnesota I see that my generation isn’t making an impact the way our elders did, and it bothers me.

Public Relations Assistant for the NFL

I’ve got this great corporate job. I am the public relations assistant for the NFL, working for PR Director Greg Aiello and doing special assignments for Commissioner Paul Tagliabue. One day the Commissioner said to me, “Angela, I have a feeling that you are going to walk out of here and it’s going to leave such a hole in our program because of the great work that you do. I don’t want that to happen, so I think you need to start your own business. I will help you do that if you train the person that comes after you.”

I was like “No! I love this.” I was just learning New York, just making contacts, but he said, “Don’t underestimate yourself. What do you want to do?” I was planning a lot of their special events. I said, “I want to do community outreach in public relations.” He said “So do that! Start your own consulting business. I will send you clients. You can do the community outreach and special events and you’ll be fine.”

Community Outreach for Fortune 100 Companies

And that’s what I did. Before I knew it, I was planning events for a lot of major fortune 100 companies, doing their community outreach, making corporations more prevalent and respected by their minority patrons. But that wasn’t sitting well with me. I felt like I was just the token Black making a living off her people: helping white folks look good about taking all our money and not giving back. And that is why I created Black On Black Development.

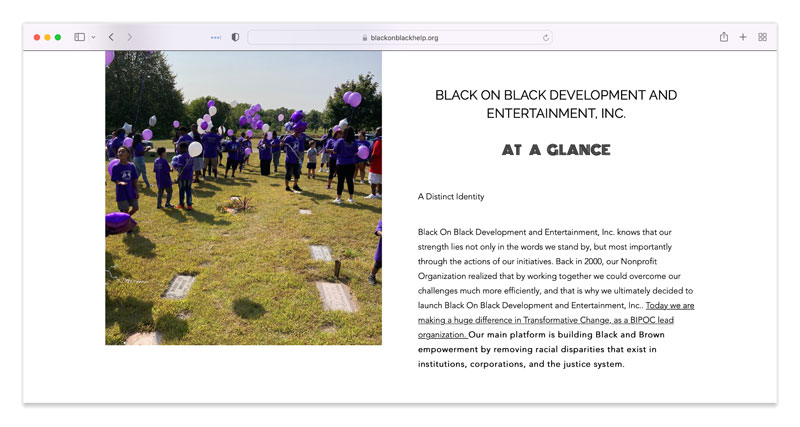

Black On Black Development and Entertainment, Inc.

I formed Black On Black Development and Entertainment. Inc. in the year 2000 when I was experiencing so much systemic racism in corporate America. I was so tired of not being understood respected and advocated for. I saw how my white counterparts, dealing with the same situations or struggles in their jobs, didn’t get pulled into the office, didn’t get reminded of their job responsibilities or that they were on probation and could be replaced at any time. They were given more understanding, more leeway, and sometimes their issues were completely overlooked, while I was held to every standard. Sometimes those standards were manipulated to get rid of me, because they didn’t expect the type of excellence that I was contributing, and it made them uncomfortable or threatened. So, I would often switch from one job to another.

The name of my organization confronts the fact that most of the time “Black on Black” is paralleled with a negative. I wanted to parallel it with a positive and let my people understand that they don’t have to look at that combination as a stigma. We have to control that narrative. Many times, when I was looking for sponsors, board members or submitting grants I would get approached with changing the name. I was told it was a character flaw for the organization; it was too abrasive. Even people I admired and wanted on my board didn’t want to sign on because of the name. But I refused to change it, because I wanted the goals and the model of this organization to be known. I had to remain true to myself. It was one thing being in corporate America and not getting the accolades and respect that I deserved. I refused to do water down something that I created with my own blood, sweat, and tears.

It was a challenge for many years. Only in the past couple years, has the phrase “Black on Black” been applauded and used in headlines and in other organizations’ missions. Now everyone wants to be part of Black transformative change. I’ve been screaming this for 25 years and the world said get rid of it, but now it’s cool and everyone wants to say “Black on Black empowerment; Black on Black development.”

9/11 and How the Birth of My Son Saved My Life

I met my husband in 1997 in Brooklyn. In 2001, I was pregnant with my son—my only child—when I was contracted by a stockbroker in the World Trade Center, Tower One, who offered to share her office with me for Black On Black Development.

My doctor said “Your baby wants to come early. You must go on bed rest.” I said “No, I just started my business!” I had also just recorded a single as vocalist and it was playing on the radio. I had promotions to promote, tours for my new song. I couldn’t just go on bed rest! But he said, “This is not an option, it’s about your baby’s life.” So of course, I chose my son’s life.

I couldn’t work. My husband had to work. That’s when my parents and my siblings kicked in and said, “Come home and we will take care of you.” So I left my job working in the Twin Towers and came back to Minnesota. And then 9/11 happened. I had been working in the tower where the first plane went down! So, my son saved my life. I still have my stationary in a frame on my wall as a testament that I was working in that tower. I tell my son every day—he’s 20 years old—I say look, young man, you saved my life and that means you have a purpose. Don’t you ever forget that.

I came back to New York with a baby. Our marriage was under a huge strain after 9/11. We both looked at life differently. I gave up my singing career. I was raising my son and making sure he had a good life. My husband and I separated in 2003, and I came back to Minnesota with my son.

Back in Minnesota, I started to call out some of the people who had benefited the same way as I had from our elder mentors, and said, “Look, we’ve got to do something to give our kids options, because they are going in totally different directions. They have no guidance. Parents are working two jobs and we are not there to supplement that as a village.” Some people said, “Who the hell does she think she is, being away so long, popping up with all her criticisms?”

I put every effort into transitioning Black On Black to Minnesota, because now it was not only just my source of income. It was a very passionate project to me. Now I’m raising a child in Minnesota. I’m not just talking about other people’s children. I wanted to make sure my son had the quality of life that I had in Minnesota.

I started small. I became the PTO parent. I wrote grants for our library and playground. I started planning events for the kids in my son’s class at Maxfield Magnet School in Saint Paul, where he went from K-6. Pretty soon people started saying, we get what she’s doing. More parents became active, I secured more board members who were capable of networking for the organization.

We started funding out of our own pockets because we saw the smiles on the face on our kids, we saw how their grades went up, and we saw how many single mothers started participating in our parenting classes and attending more events at their kids’ schools. We started workforce development right in the schools for the young mothers so they could get it all in a one stop. It was making a difference. We just started being our own reoccurring donors.

My son was now in junior high. I’d gone from a house in 2003, to a subsidized apartment in 2013. With a teenager, things are more expensive. People were saying, “Oh you live in those projects over there.” The things that I didn’t want to affect him were happening.

Grants were not coming in. After the Great Recession hit, donations dwindled. I created an internet fundraising campaign, and I received several fraudulent donations: people turning in their unused gift cards. I had a credit card verifier, so I thought, what could be wrong? Walmart gets fraudulent charges every day and they don’t get sent to prison. They’re credit card verifier takes responsibility and the insurance kicks in and everything’s fine.

Well, that didn’t happen for a Black lady running a nonprofit. I was charged with identity theft, which led to the injustice of me becoming a prisoner and having a felony.

Entering the Criminal Injustice System

That’s when I realized the extent of injustice and systemic racism within the justice system. People like Denny Hecker take millions and spend seven years in jail. Sheriffs with gambling habits take $200,000 and they get probation. My charge was aggregated to 10 to 20 years for $35,000 worth of gift cards.

I was hit with a law that had never been used in the state. My jury was hung. They were confused. They were like, “This lady couldn’t have committed all these robberies. That’s not a one-person thing, and we’re not even sure who the people are that are purchasing these stolen gift cards that were donated to her.

Judge Alshouse told the jury, “I want you to go back in there and give me a unanimous decision.” I waited, in vain, for my state public defender to object and say, “those are improper jury instructions.”

It was the Friday before Memorial Day weekend, when no jury wants to deliberate. They went back in and came back with a guilty decision. The judge ordered the sheriff to cuff me immediately and revoked my bail.

After sentencing me, Judge Alshouse retired.

Fighting Boot Camp Discrimination

So now I’m doing ten years in Shakopee Women’s Prison. I wanted to go to Boot Camp, a treatment program, because I needed to get out of there. If you can make it through Boot Camp you can get out in six months.

I get to Boot Camp after I’ve been in prison two years. My squad sergeant told me, “We don’t like smartass Black girls.”

If you don’t have any history of substance abuse, they contest your right to be there. I didn’t need treatment counseling. I needed a psychologist. I needed a mental health counselor. I was there for critical thinking. I was kicked out of the program for “derogatory statements.” I appealed.

Everyone told me, nobody appeals Boot Camp. I said, “Well, they have not dealt with someone with my intelligence, drive and know-how. I’m not just going to sit here and do time.”

I appealed on the basis that I have a right to mental health treatment. They let me back in, but Commissioner Roy and his administration set every trap they could to make sure I didn’t get through that program and out in six months. His attitude was You’re going to do years for contesting us, for giving Black women in this prison the idea that they have a voice, for proving that Black people are intelligent and can win and be empowered.

Boot Camp created a “critical thinking treatment,” specifically for me, which consisted of cleaning the urinals in the male officers’ bathroom. My sergeant insisted that I could not clean in my sweats and tennis shoes. I had to do it in full uniform and if I scuffed my boots while cleaning, I had to run two miles. They were determined to make me quit.

I called home and I told them what was happening. My mom said, “You’d better be the best damn toilet cleaner they ever ran into.” But they found reasons to demerit me. After you get so many demerits, you’re automatically terminated from the program, so once again I was kicked out.

When Governor Waltz came into power, Commissioner Tom Roy was replaced by Paul Schnell. All of us prisoners thought this was the light at the end of the tunnel. Boy, were we wrong.

Finding the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee

I had my mom scouting for prison reform organizations. Another young lady who was incarcerated heard about this program, the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC). She said, “I don’t think it’s going to help me much, Angela. I am going to be here for a long while, so I don’t want the harassment, but I think you have the strength to endure whatever they bring your way.” She put me in touch with IWOC, a group of former prisoners, their family members, and outside advocates.

I thought, well, if I don’t get back into the Boot Camp again, at least my family and I will have some support. I’m going to give them hell for discriminating against me and I’m going to be the biggest advocate for people on the inside. They’re going to regret ever making me stay here.

My parents and I held the very first press conference on the discrimination of Blacks and minorities in Boot Camp. We pulled up the numbers showing how few of us had been even accepted, how very few graduated and how many of us were terminated from the program. We went straight to newly-elected Attorney General Keith Ellison’s office.

My mother was one of the first 911 operators at the Saint Paul Police Department. She had formerly worked with Paul Schnell when he was a police officer, so they were on a first name basis. Nevertheless, Commissioner Schnell never allowed me back to Boot Camp.

Organizing Inside Prison

That is when I started working on policy change in prison. They put me in segregation several times for what policy calls “inciting a riot.” I was trying to organize prisoners and gather minority women together. I realized this is set up. We can’t even fight for ourselves. This is a mass machine to keep us all oppressed. Prison operations are so shielded from public view, that they don’t have to follow the law. We’ve got to expose the injustices, put them under the microscope, to make policy changes.

After we did the press conference, we went after the mandatory minimum policy. We got some rewrite, and all those ladies got into Boot Camp.

When the 2/3 law passed, my sentence was dropped to seven years.

COVID and Prison Medical Release

I had been in prison for five years, when along came COVID. I have high risk health conditions. My doctor said “She’s got to go home.” I was released on June 24th, 2020: early medical release, but with a million conditions. I wasn’t allowed to work! So how was I to survive?

I can’t be in congregated settings. I’m under house arrest, except for essential appointments. Few are going to succeed with those conditions.

So now I’m fighting from my laptop, in my elderly parents’ home. They raised my son for five years. I’ve missed all his high school. Now they have to take care of me because of these parole conditions. I’m living with my parents, with a grown son, and I’m not even sure where I’m going to get my next dollar.

Organizing for Prison Safety from the Outside

I go on the news again because inmates are dying like flies. The prison administration were not following practices mandated by the CDC in the prisons: proper PPE etc. They put conditions on the people they release, that send us right back to jail. We need to tell Health Commissioner Jan Malcolm and Governor Waltz, “You’re letting people go in and out of prison infected. People are going to their families or going to treatment centers or halfway houses or to the doctor and the grocery store. You must get a grasp on this.”

Prison facilities need to be socially distanced. You can’t do that with four people in a cell. You can’t do that with double-bunking. Some people are in prison because they didn’t report to their parole officer. They don’t deserve to die of COVID.

But they just want the federal dollars; if they kill a few people who cares? The county jails stopped double-bunking, but not the prisons. So we have people returning to prison because they can’t get a job, and couldn’t find housing. People in prison on a technicality, who should have been released, are now facing a health crisis, due to prison negligence.

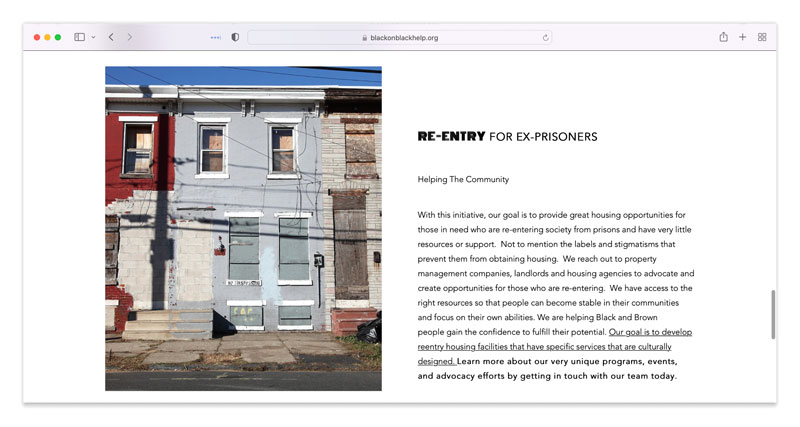

These are the issues we are addressing in our campaign. I started advocating for 25 prisoners, both men and women. I ask individuals and organizations to help with reentry housing, hygiene donations, and assistance for kids.

Organizing Without Rights

So now I’m a member of two organizations: my own and IWOC. I hit the ground running as soon as I got out; I immediately started advocating and submitting proposals for grants. I was told that because I had a financial fiduciary charge, I couldn’t put Black On Black back together. So I fought that. Then I was told, “You can put the organization together, but you can’t have fiduciary responsibilities.”

I called the Department of Labor and asked, “Since when do parole officers, community supervisors or the DOC have the authority to tell an organization how to run their business or who they can hire?” This type of systemic racism has lived and breathed forever. We have accepted it forever.

Organizing After the Murder of George Floyd

Before the death of George Floyd, if you were challenging the status quo, then you were a troublemaker. I think the change began with the death of Philando Castile, but it exploded with the murder of George Floyd. It’s been like a moth to a flame; like a flashing billboard. All this funding has been thrown into the world to be dispersed to Black-led organizations.

I have mixed emotions about who is getting the applause today for their anti-racism work. The pioneers on the front line 25-30 years ago, we’re not getting that $100 billion in Black transformative funding. There is money available now, but if you’re just a small grassroots organization there are barriers. They want you to prove profit and loss, etc. That money is supposed to be for us right? Just give it to us. What’s all this paperwork?

We Need Post-incarceration Assistance

As a 53-year-old woman, I have pride. I don’t want to ask my parents to go buy something I need. I’ve gone to Social Services, to Human Services, you name it. There’s no program for a healthy, able adult. It sends the message that being an addict or hurting yourself so that you are disabled, would make you more acceptable. Where’s the program for the person who’s fighting for this American dream?

You can’t build leaders or empower people, until you make them whole. I see leadership programs, but I don’t see mutual aid. Skills and education are difficult to acquire if your mental health has not been addressed. Parenting skills, and work-force training will not be grasped without addressing core issues of historical trauma. That is what I hear again and again, when I am doing my advocacy work. People tell me, “I can’t focus on a class.” That is why these programs are not successful.

Black On Black Now

So now Black On Black has taken on a whole other dimension. As the executive director I’m experiencing unbelievable situations. I see people who don’t have parents or a partner or someone who can sustain them. They’re going to go back to prison.

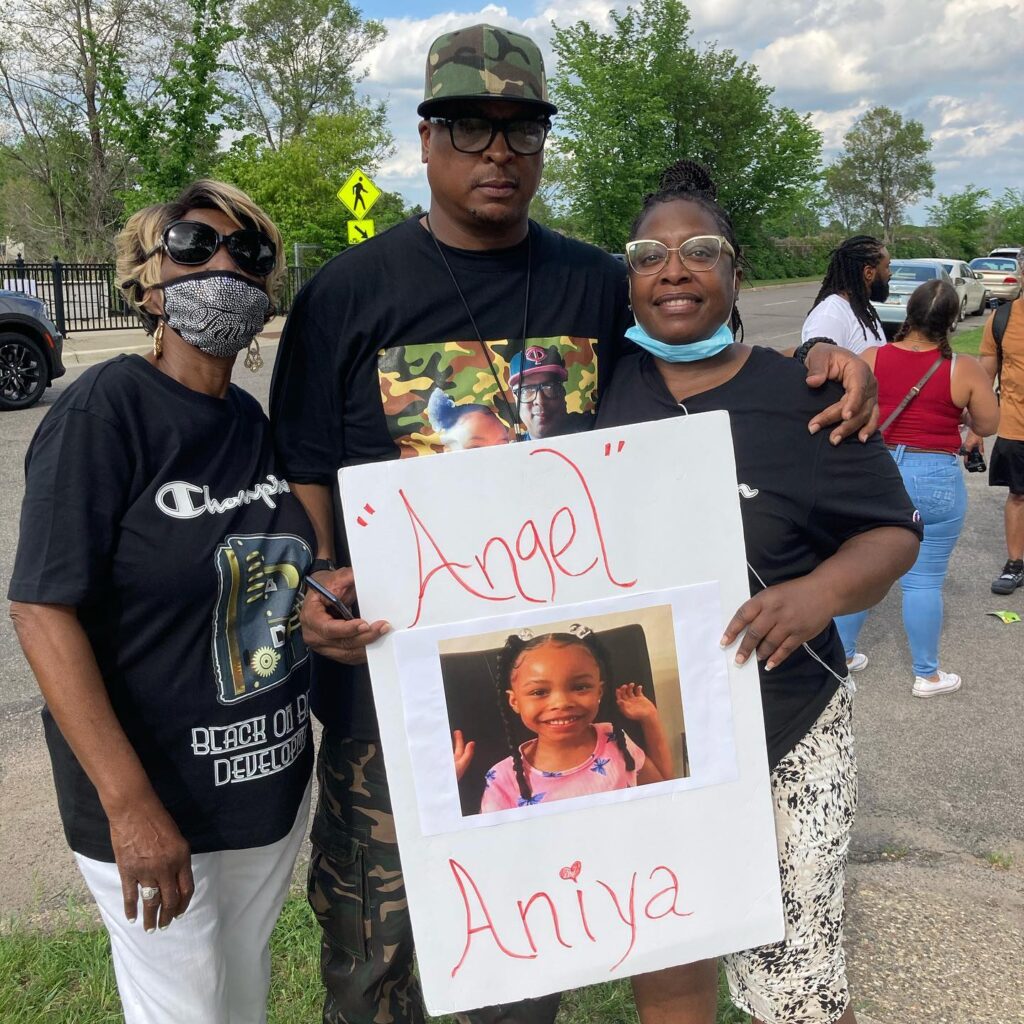

After three children were shot in Minneapolis, I started an accountability campaign in my neighborhood. I have a board; my mother is the chair. I have a few volunteers. I’ve been partnered with the TRUCE Center. Their executive director and founder, Miki Lewis-Frost, has the same goals, so we partner on different functions. And of course, I partner with IWOC on abolition and prison reform.

We have also set up a fund for artists and musicians to sustain a living during COVID. We helped them create virtual platforms so that they could maintain income when venues were closed. We just received the St. Paul Cultural Star Grant and have named it the Starving Artist Project. the purpose of the project is to open the arena of downtown St. Paul to cultural artists.

I will not stop fighting for the village, to empower us, to make us whole, physically, mentally, financially, so our leaders will not be fly-by-night, or negatively impacted by the work we do.

To donate to Black On Black