Poetry was a space for healing the trauma of having been an immigrant, being queer, being from Honduras… I was able to tackle questions of shame, being in the closet, being poor, seeing my parents struggle and not get ahead. There was something quite beautiful, poignant and maybe even radical about my ability to locate the source of my issues; to see them on one page in crystallized form. Poetry allowed me to be more vulnerable and confrontational with myself: to say, “Name it Roy. Is this really how you feel?”

— Roy Guzmán

(Note: Excerpts— indented—with titles and page numbers, are from Catrachos, by Roy Guzmán, Graywolf Press, 2020.)

Tegucigalpa to Miami: Immigrant Childhood

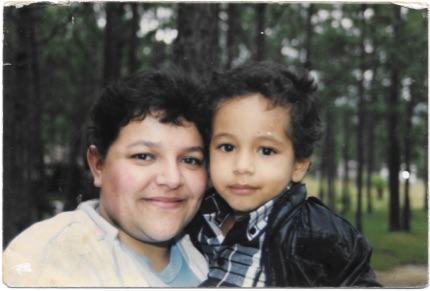

In Honduras, I was raised by my mom, my aunt, and my grandfather. They grew up in poverty, but by the time I came into the family, we were low-middle class. My mom was a secretary, a job that in Honduras in the 1980s meant you had more education and higher social standing than most people.

When I was nine, my mom went to the US where she got work cleaning houses. I followed her a year later. We had visas, but when we overstayed them, we automatically became undocumented. I couldn’t go to school. I wrote about going to work with my mom in the poem, “American Dream.”

I am the only child

who goes to work with his mother—the others

haven’t saved enough money to pay for a coyote.

Sometimes we share Berger Keen. Sometimes

Maldonal. Under a managerial sun, we revolutionize

The concrete benches with our tired asses,

exhume stories of lands we are too afraid

won’t recognize us if we ever go back. Because if we do,

it’ll be against our will. Because our grandmothers

require insulin. Because those grandchildren

need school supplies.

Excerpt from “The American Dream” pp. 23-24

We lived primarily in Allapattah, a poor immigrant barrio with people from all parts of Latin America. It is very industrial, filled with factories, freight trains, container ships, violence and poverty. The Miami River runs through it. When I did start school, I was placed back a couple of grades. I went to six schools in eight years. Sometimes it was in a completely different neighborhood and I took public transportation long distances.

My stepdad is Cuban. By the time I came to the US, my Mom was dating him. He worked in factories. When I was an adolescent I didn’t have a bedroom of my own. Sometime I slept in the same room with my Mom and stepdad, sometimes there were other people, sometimes I slept in the living room. Going through puberty without privacy was kind of weird.

Today my mom is a salesperson at Best Buy. My parents live in West Kendall where they were able to barely afford a two-bedroom apartment. I lived there with them before I moved to Minneapolis. For a while it was affordable, but now West Kendall has become too expensive.

Chicago

I did two years at Miami Dade College, graduating with an Associate Degree in History, before transferring to the University of Chicago in Comparative Literature. That was a radical change. There were so many things that I was exposed to for the first time — for better or worse. The university is on the south side of Chicago, and the school had many issues with the surrounding Black communities that exposed their racism. I had to take out student loans just to survive there. As a result, I carry a lot of student debt. I wasn’t used to being surrounded by so much wealth within the school and I faced class and race discrimination. People mistook me for a janitor, or the child of college janitors. I was deemed unattractive because of the color of my skin. I wrote about my experience at the University of Chicago in my poem, “Marrow.”

the Fall is maybe symbolic

for how deep we’ll burrow within us to still blame ourselves

for holding the map of rejection, that map with subjugated

creases, see Fig. 1 for assemblage, see Fig 2. for the leper

who cries for clemency in the metaphor

Excerpt from “Marrow” p. 45

After college, I worked for a couple of years as a paralegal for a disability/social security law firm with clients who were disabled, facing financial, and physical hardships. I learned a lot from the attorneys, my fellow paralegals, and the case managers about how to address classism, racism, and ableism with empathy. I also learned that I did not want to be an attorney. You need incredibly thick skin. I have always seen myself as having an advocacy spirit. The law often doesn’t care about people’s individual needs. It was hard for me to swallow that kind of reality.

Working there I was able to learn more about the city. As an undergrad, I felt isolated and disconnected from it. Now I was exposed to its complexities. I told my partner that I might want to retire in Chicago, where you have access to older, distinct neighborhoods, where people have identities that connect them—Polish, Chinese, Ukrainian, African American, Latinx. I do love the public life here in the Twin Cities: the festivals, art, museums and restaurants that I have been missing since the pandemic. In Chicago, all of that is on a much larger scale.

Master’s Degree in New Hampshire

From Chicago, I went to Dartmouth in New Hampshire to get a master’s degree in comparative literature. It was a one-year, super accelerated program. That was a beautiful experience in an area I thought I would never live in. I would go to visit Boston, Montreal, and Burlington. I even considered living in Burlington but ended up coming back to Florida, working as an adjunct.

Adjunct Instructor to Latinx Students in Miami

I still work as an adjunct. Here in the Twin Cities, I can usually create something sustainable with two or three classes a semester. To make it in Miami, I taught nine classes one semester! I lived with my parents, we shared expenses and I was able to help them get a bigger apartment. Despite the financial reality, I am fond of my memories of teaching in Miami. Interacting with Latinx students all the time, I was able to understand my own identity more. I hesitate to use the word empower, but certainly, I was able to share resources and skills with my students that they could take in new directions. I taught English composition and literature. I did not have the credentials to teach creative writing. I started to desire an MFA.

It was during this time that I found myself writing, reading, and tackling my background through poetry.

Finding Poetry

when you’re brown and gay you’re always dying twice

“Restored Mural For Orlando” pp. 49-51

I say to people that I came to poetry because I felt that it was a space for healing. I was able to address a lot of stuff I didn’t have the language or the genre for before that. The trauma of having been an immigrant, being queer, being specifically from Honduras—I didn’t have a large diaspora community like many other Latinx people in Miami. I was able to tackle questions of shame, being in the closet, being poor, seeing my parents struggle all the time and not get ahead. There was something quite beautiful, poignant and maybe even radical about my ability to locate the source of my issues and to see them on one page in a crystallized form. I could say this is the monster, the source of my issues. I had never been able to call it what it is before.

At the same time, I think that poetry also allows me to work in a different kind of tone, and a different set of expectations than something like an essay. It allowed me to be more vulnerable and confrontational with myself, to say, “Name it Roy. Is this really how you feel? What if you were to create a metaphor to get at that distortion, that trauma, whatever it is?”

After the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando, in 2016, my poem “Restored Mural for Orlando” was turned into a chapbook. With poet Miguel M. Morales, I co-edited the anthology Pulse/Pulso: In Remembrance of Orlando, published by Damaged Goods Press. The memory and vicarious grief of the Pulse massacre will always stay with me. The process of writing about it altered how I think about the possibilities of poetry.

Seconds before the shooter sprays bullets brother’s and sister’s

bodies / the DJ stops the record from spinning / & I am interested

in that brief dazzle of pink light / how it spreads on iron pressed

shirts until they are purple / how a gun is a heart that has forgotten

to sing. The rapture in a stranger’s eyes /a candid take on resurrection

You visit Orlando to fantasize about the childhood you didn’t have.

Excerpt from “Restored Mural For Orlando” pp. 49-51

Now, after having been through the MFA, I feel like any genre can be that space to do self-reflection—even fiction. I love the essay form and so much of what is going on in non-fiction. The beautiful thing about the MFA at the U is that it encouraged you to work in more than one genre. It motivated me to say what can this genre do for what I have in front of me—for this story I want to tell.

Finding Home in Minneapolis

When I lived in Chicago, Minneapolis felt like—you know in the Game of Thrones? —going north of the wall.

As a Honduran poet researching MFA programs, I didn’t find many Latinx professors, and most of them were in the southwest. I am not a huge fan of warm weather, even though I grew up in Honduras and Miami. I wanted a colder place. The University of Minnesota had Ray Gonzalez and cold weather.

I completed my MFA at the University of Minnesota in three years and decided I wanted to teach. Since most places want a Ph.D., I started to think about my larger theoretical interests in comparative studies, comparative literature, and critical theory. Since I had already developed a lot of community here, I applied to the program at the U of M in cultural studies and comparative literature. I fell in love with the way the department presented itself. Right now, I am in the middle of my fourth year at the U. I should be done with my doctorate in three more years. This is my seventh year here. Ideally, I will find a tenure track position here in the Twin Cities and be able to stay, but as you know, the academic job market is tight, and when you are up-and-coming you have to be open to moving to the middle of nowhere. I am open to that, and my partner, of course, would come with me, but we are really trying to grow roots here.

I love it here. I have found support through creative communities at The Loft, Century, the U of M, and my editors at Graywolf Press. I feel very lucky that I have a publisher with both a local and international stamp. I love that about Graywolf. Once I complete my dissertation, I hope to submit the book to one of my favorite academic presses: The University of Minnesota Press.

Seeking A House when Flippers Dominate the Twin Cities Market

Since I moved here, I have always lived in the Uptown or Whittier neighborhoods of South Minneapolis. My partner and I have been looking for houses to buy. Renting is going up so that in some cases buying a house is cheaper. But it is a mess out there right now because of COVID. People with income during the pandemic have been buying properties to resell them. A lot of people looking for places to live, are being left out of the competition for houses. We are seeing this in real-time. We have seen about 15 houses. We put offers on four houses. We were outbid. One house we put an offer over the listing price and still lost it. That house had received 24 offers. It can be a depressing experience—you fall in love with a house, and then you lose it. We are looking for houses anywhere from Richfield to Maplewood and beyond. When my book came out, I delivered about 10-15 copies thinking I could deliver to zip-codes close to home. That was an overwhelming idea. But the copies I did deliver allowed me to see some very beautiful homes in South Minneapolis. Of course, this was at the beginning of the pandemic, so I didn’t go inside.

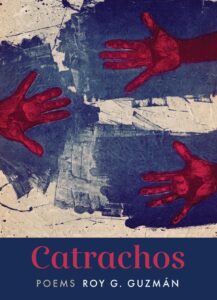

Catrachos: Poems by Roy Guzmán

In the mid-1800s, William Walker, an American filibuster, attempted to take over Central America and reimagine the region as a slave colony under United States rule…. He was eventually defeated by Honduran General Florencio Xatruch’s troops.… From Xatruch’s name, Salvadorans became known as salvatruchos and Hondurans catrachos.

Excerpted from “Note on the Title” p. 93

The majority of the book I wrote here in Minneapolis. There are maybe two or three poems I can trace back to Miami. Of course, they went through major revisions. I wrote the book at Victor’s Café, at Caffetto, at Butter Bakery and the Original Pancake House. Now that we can’t work in those spaces it has been tough. Since the pandemic we spent a lot of money, unfortunately, supporting those businesses, having food delivered to us. I found inspiration in those places from the music, the lighting, the sound of the espresso machine, the people around me.

Some of the best experiences I have had around the book, are visiting classrooms virtually, and having people teach the book or share it in the workshop*. Some people have asked me questions about the revision process, how to start a poem, working in more than one language, the issue of Spanglish.

There is often this question: “What if your audience doesn’t understand cultural references?” I say, look it up—that same way I do with books I have loved about places and people who are not me. I don’t expect every book to provide an introduction to—say—England, Maine, or New Mexico. I expect the language in the story to be so inviting, inventive, risk-taking, that I will want to dive deeper. It has been important to me to stick to this point. I don’t need to be a translator or an informant of my communities or the identities that make up who I am. I can provide different routes of entering that material. Some people have enjoyed the note section in the back of the book, not because they suddenly understand what the poem is doing, but because it becomes a place to look up other things that have influenced me, other than what is in the poetry.

*To book a workshop with Roy, contact the Shipman Agency.

Honduras

When I found out on January 30th, 2021, that Catrachos was a finalist for the Minnesota Book Award, for poetry, I thought about the larger historical context of this honor. Catrachos is most likely the first book by a Honduran/Central American to be a finalist in this category. Given the US’s military interventions in the region, this is monumental.

I have a lot of cousins back in Honduras. I have visited twice since I have been in the US. I was hoping to go back in 2020, to do some research, but then the pandemic hit. Recently they have been hit with hurricanes, destroying villages in different areas of the country, disenfranchising people who are already poor, who come from communities that already had few resources. There is still a lot of violence perpetrated by gang activity, but also the government which has been caught in all kinds of fiascos, from corruption to mafia tactics— giving certain families access to resources, and limiting it to others, creating an atmosphere of censorship, engaging in extortion. The government hasn’t done an adequate job of working with institutions to make sure there is justice. Femicide continues to be an issue.

My grandfather in Honduras died from COVID 19. I had other family members who were very sick with COVID and almost died. I was able to raise money through social media to help them a lot, but there is this grief that I carry. My mom has also been experiencing a lot of stress—low appetite, things like that—and I feel that.

2020-2021

I have a friend who died yesterday — a former choirmaster in Chicago. Not being able to visit my family in Honduras when so many were sick with COVID, was painful. When we can’t hug our loved ones, we can’t have closure.

I am skeptical but also positive about this new administration, that they will help us with pandemic, the homelessness and the families who have been most affected by this economic crisis.

I grieve not being able to do justice to my book. The tour that Graywolf had planned was canceled. But I am grateful for the virtual events. This week I am doing workshops with the University of Texas, Dallas. This is not how I imagined the book would roll out — I imagined being there, with my book, at a reading, to hug people and answer questions — but I am grateful that through the virtual communities I have been able to access people who would not have had access to the readings, people with disabilities, people living in other countries.

I am hoping that 2021 is a year when people can have the time and space to do more reflection. I am hoping we can do more justice around issues that affect Black and indigenous people. We need more art out there. We are dealing with the whiplash of these past four years. We need new ways to imagine what tomorrow can be.