In the early ’70s I moved near Powderhorn Park and lived in a commune with members of the Twin Cities Women’s Union, a socialist feminist organization. We ate together occasionally and bought groceries together. I was the only man who lived there–a one-man, male auxiliary and observer of the blossoming of militant feminism. It felt like being deconstructed.

—Tom O’Connell

Catholic St. Paul Roots

I grew up in St. Paul going to Catholic schools, including St. Thomas Military Academy. Due to my religious upbringing, I knew I was lucky that I had middle class privilege. When I read The Affluent Society by Kenneth Galbraith, I thought it described my father. He served in World War II, became a salesman just as the post-war economy was taking off, and was successful enough for our family to move to the Highland Park neighborhood. At that point he gave up climbing the economic ladder and enjoyed his family, his friends, his golf.

Radicalization at St. John’s University

I went to college at St. Johns in Collegeville, MN. The years 1965-1969 were an interesting time to be at a Catholic Institution. Vatican II, provided an opening in the Church. There were a handful of monks and lay teachers influenced by the most socially conscious aspects of this movement within the Church.vBy the end of the first year I had renounced my membership in the military academy.

I studied history, which is a radicalizing experience in itself. Senior year we formed a “Christian living and learning community”– five women from St. Ben’s and ten men from St. John’s living together off campus with a monk for a chaperone. We called ourselves, “the farm.” Those people are still close friends. Classes at St. Ben’s and St. John’s were gender-segregated so it was my first exposure in college to women–a life-changing experience.

The Open School Movement

After college I moved into a commune on Laurel and Milton in St. Paul. Now the neighborhood is more gentrified, but in 1969 there was disinvestment going on. White people were moving out and it was becoming a racially diverse, mixed-income neighborhood–a perfect place to start an alternative housing community.

The nine of us in the commune were part of the nation-wide Freedom School Movement. We started two free schools in St. Paul, the “Community School” and “Common House” — small, alternative high schools of 35-40 students. We had no curriculum to speak of. One of my best memories of that time. was taking kids on a trip to Mexico in an old school bus.

Elsewhere in the Twin Cities, people opened Street Academies. The first one, “Freedom House,” was in North Minneapolis. Some of those Street Academies still exist. They became alternative public schools for kids who struggle in the classroom and are having trouble with the law.

There were two models within the Freedom School Movement of what “free” should mean in a school setting. One was classic American. It was negative and individualist, adopting the philosophy that, “I can do whatever I want, as long as it doesn’t hurt you.” The other was social movement-oriented, focused on engaging with other people in solidarity, to achieve together what we can’t achieve by ourselves. I supported the second model.

I worked with the Education Exploration Center, housed in the old Walker Methodist Church in South Minneapolis. It was a clearing house for the alternative school movement. We had conferences, published a newsletter, and put on salons. We brought in speakers: Jonathan Kozol, Herb Kohl and Ivan Illich. One of the most influential thinkers we studied was Paulo Freire. We spent a year trying to understand how we could use “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” in the Twin Cities. Years later I was on a panel with Freire.

Finding My Place in the Minneapolis Southside Left

In the early ’70s I moved near Powderhorn Park and lived in a commune with members of the Twin Cities Women’s Union, a Socialist Feminist organization. It was not as communal as Laurel House. We didn’t pool income. We ate together occasionally and bought some groceries together.

I was the only man who lived there — a one-man, male auxiliary and observer of the blossoming of militant feminism. It felt like being deconstructed. It was hard. We fought. I was a typical male, coming from a family of three boys. I believe if I hadn’t had this , (and earlier communal experiences at St. Johns and on Laurel Avenue), I would be totally lost about how to relate to women. I was dense about sharing household chores. I had always been the leader, always class president, always the one at the front with the gavel. I needed to learn to step back and find different ways to be a man. It was liberating, but it wasn’t a straight shot. Lots of detours.

The Minneapolis southside radical movement was not unified. Some of the differences were cultural, having to do with the counterculture movement. Other differences were deadly-serious political.

A group of us thought revolution would be accomplished through the growth of alternative institutions, different ways of living together, and building alternatives to capitalism. Others wanted to confront existing institutions, whether they were banks or corporations.

It was a rich time; lots of really good people; lots of stress and anxiety about being middle class. We were really hard on ourselves and each other. We felt a responsibility to introduce socialism and radical analysis into the labor movement. There were many reading groups and study groups. We read Marx and Lenin.

By that time, the AFL-CIO had driven out the Communists, and labor unions had come to see themselves as junior partners in Capitalist development. They had achieved middle class wages for working people, which was incredible.

I worked pretty closely with Communists in coalitions and at one point was invited me to join the Communist Labor Party. I admired people who were in the Party in the Cities. It wasn’t a large group. They were predominantly working in the labor movement, doing pretty pragmatic stuff. We operationally had the same politics. The difference was their Party wasn’t for mass consumption. I didn’t want to be part of group I couldn’t be public about.

The other thing about them is that they had this one strange platform: you had to agree on creating a separate nation in the south for Black people. I said, I get it, I understand the progressive motivation, but I didn’t think we are headed there. There were probably others planks in their platform I wouldn’t have agreed to, but that was a deal breaker.

In the 1980s I got involved in the Central America movement. I saw what was happening in Nicaragua and Cuba as akin to what we were doing on a neighborhood level—creating anti-Capitalist, democratic socialist institutions. I visited Cuba, looking for those neighborhood councils.

I was always attracted to socialism. I studied the Russian, and Chinese and Cuban Revolutions. But every system has limits and every system has power. Capitalism isn’t the only one. I resisted the total dogmatism some in the left study groups got into. I recognized the difference between an analysis and a catechism. I had already rejected the religious dogma of the Catholic Church and I wasn’t looking for another one to replace it.

Still, growing up Catholic had a lifetime influence on my politics. You are never saved as a Catholic. You can go to confession, but you are still held accountable. You have to love your neighbor. I picked up on the communal interpretation of the theology and the sense of obligation. I think the Church helped me not get alienated and bitter like some people did, to accept limits and be historically grounded. I guess that makes me a reformer — a kind of democratic socialist.

Neighborhood Organizing in South Minneapolis

By the early to mid 1970s, I began to feel the Free School Movement was too limiting. Most of the students were dropouts from middle class families. I wanted to get involved with other social movements. It was a time when many White middle class people on the left were recognizing that if change was going to happen we were going to have to get much broader.

Many people working on local equity issues were using Saul Alinsky’s pragmatic style of organizing. Their big center was in Chicago. There was a group here–the Center for Urban Encounter–located near the U of M. I took their training, conducted by Bill Grace and Fred Smith. They advocated a pragmatic approach to radical organizing, addressing people’s immediate needs, not talking socialism because “normal” people wouldn’t go for that. They were highly disciplined in terms of how they organized meetings, and accountable in terms of tactics. I thought that while it was ideologically limited, we could benefit from incorporating some of those ideas.

Out of those trainings came the Northeast Community Federation, and the Southside Federation which I got involved in.

Separate from these Alinsky-inspired groups, we organized the Powderhorn Residence Group, which still exists. We had this idea to buy out absentee landlords and convert them into limited equity coops. Whittier School became one of those coops. The Tenants Union advocated for renters. We had a referendum on rent control, which we lost.

Through Southside Community Development Corporation we had access to federal funds. We started the Southside Community Credit Union which existed for quite a while. I know it was a legitimate thing, because I applied for a loan with them and didn’t get it. I was barely getting paid. I was able to get a Vista job, (now Americorps) and then a CITA job, using all the infrastructure available to do the work. I was living on nothing, though I had family resources. Sometimes when I ran out of money I went home. Sometimes I bounced a check. Though everyone at the Community Credit Union knew me, the loan committee looked at my financial record and decided I was too much of a risk. Like many of the other cooperative institutions they rode the line between equitable community building and remaining solvent.

We worked on public ownership of utilities. Although we didn’t succeed, we paved the way for recent campaigns for public control of Xcel Energy. Some of our efforts fizzled, like the Southside Community Enterprises.

We waged a protracted battle against the Cedar Riverside High Rises—a campaign against massive for-profit development. We fought to keep the high-rises down to two, from the five they wanted to build. Of course now they are expanding and the area is a center for the Somali community. Then we were supporting smaller-scale, neighborhood, community-controlled development.

Coop Wars

Organic food coops were mushrooming. They catered to a counter- cultural group, both in terms of who was working and shopping there. Bins of grain, very little canned food. They did not appeal to “normal” working and middle class people, so while they were an alternative to capitalism and represented community assets, they were not going to create economic change.

The battle over the coops had three sides. 1:The strictly organic people who liked them as countercultural spaces. 2: Those advocating taking over the stores to turn them into anti-capitalist spaces to serve the shopping desires of the working class, and 3. Those who were sympathetic to the #2 critique, but not the way it was implemented. I was in the third group.

The #2 group, led by a charismatic guy from Philadelphia who appeared on the scene, offered a critique and then moved a certain sector to take over stores violently. They literally became a sect. Eventually they went underground and we never heard from some people again. Families and friendships broke up. It was a painful period in what I would largely call the history of the Southside left.

Southside neighborhood organizing was decentralized, but there was a larger sense of belonging to a movement. We shared a belief in community control. Cultural groups provided a sense of community. The Twin Cities Women’s Union had their own theater called Circle of the Witch. Another radical theater was Alive and Trucking. I didn’t do theater, but I went to everything they put on. The First May Day was around then. A couple hundred people participated. Walker Church was a central place for those cultural projects.

Sometimes we tried to move too fast to implement important ideas that needed nurturing. We were guilty of socialist paternalism. South Side Community Enterprises was a case in point. We wanted low-income people on the board but we wanted them to agree to socialist forms of ownership, which meant recruiting certain people and not others. We wanted people to agree with our analysis, but there was always an undemocratic aspect of what we were doing.

There was a section of this broad neighborhood movement participating in anti-war and solidarity work, but mostly they were separate. I began in the peace movement against Vietnam, working with Clergy and Laity Concerned and later the Central America Resource Center, but my energy focused primarily on local issues. I always felt connected the idea that what we did locally had global implications, but it might have been my imagination. Making connections became easy when I began to teach.

Bringing Open-school Values and Community-building Skills to College Teaching

I never planned to be a College Professor. My friend, the late Larry Olds, had lived in the Laurel House Commune, and was a key leader in the alternative education movement. He worked at Minneapolis Community College (now MCTC) and invited me to teach a class in their College for Working Adults program.

CWA started in Detroit, connected to the Walter Reuther Center at Wayne State University to provide higher education for Auto Workers. The curriculum consisted of very bad television programs — talking heads— and weekend sessions focused on integrated themes, like “Work and Society.”

The teaching job in 1979, came at just the right time financially. I was reaching a crisis point, as many of us were in the barely-paid movement.

I signed up for a Union for Experimental Education program at Antioch, to get a Ph.D. without going to class. I documented my study of, “Creative Organizing” and “Advanced Creative Organizing” and “Marxism” and “Advanced Marxism.” I began to see the degree as a balloon mortgage: you kept paying in and it kept getting bigger.

I taught at Carleton a year—that was Paul Wellstone’s doing—and then I got hired full-time at Metro State.

Back then, Metro State had two offerings: a Bachelor of Individualized Studies, and a degree in Nursing. The Individualized Studies program had no grades, no majors, no departments. I was against departments, but for grades. Eventually we got both, after years of very heated and painful discussion.

We formed an interdisciplinary social science department. Somewhere along the line I became President of the Inter-Faculty Organization at Metro, and we tried to deal with the inequality experienced by Community Faculty, by creating more full-time positions, circumventing every rule to do so. To deal with affirmative action, we set aside positions for faculty of color, which was also illegal. I enforced that and got sued by a dear colleague.

I told people, if I’m still teaching in ten years come get me. But I stayed for over three decades and came to love it.

Farmer/Labor organizing: 1930s and Late 1970s

We used to say, “Never trust anyone over 30. ” Then you become 30 and wonder, what the hell are you going to do next? First of all, you exempt yourself. The second step for me was to become interested in what and who came before.

Writing my thesis on the Farmer Labor Movement, interviewing old radicals, was inspiring. It helped me strategize how to re-energize those Minnesota’s radical roots excised from the Democratic Party in the 1950s.

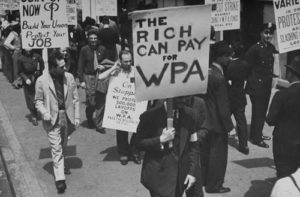

Issues in Minneapolis in the 1930s would be familiar to activists today. People organized the unemployed and public sector workers. Women took leadership. They lobbied the welfare board, marched on the Capital and City Hall, demanded a livable city, advocated for progressive education, organized for a minimum wage. There was the 1939 WPA workers’ strike, unemployment marches, and of course the 1934 truckers’ strike. Socialists and Communists, labor unions and women organizations fought together for basic needs.

In the late 70s we formed a new Farmer Labor organization. Some of the old timers showed up. Some were Communists. Most were aligned in some way with the left-wing of the DFL party. They were happy we were reviving the old movement. Paul Wellstone and Karen Clark were leaders of that effort. Karen Clark was our first electoral victory. We had chapters on the Iron Range, in Duluth, South Minneapolis, North Minneapolis, and St. Paul. We called for a moratorium of farm foreclosures, rent control, public ownership of utilities. I think we had a plank on Central America, but I’m not sure. We opposed military spending.

In Minneapolis this organizing facilitated communication between Southside and Northside activists. We supported a Northside candidate, an African American woman running against the Northside machine. It was a good campaign, even though she didn’t win.

Coming Full Circle

I retired four years ago. Initially I was defensive about that word. I didn’t want people to think I wasn’t being socially productive. The first year was hard, but now I’m mostly happy. I have actually gone back to working the way I did when I was young, only with financial security. I have a pension, which is a blessing and a privilege.

I tend to work in small groups on projects. Some of them are things professors do when they aren’t overwhelmed by administrative education issues. I am working on a documentary film on the Farmer Labor movement. I wrote a book on Community Leadership. I’m working on a second book.

I am Chair of East Side Freedom Library, a wonderful alternative meeting space for cultural, labor, race, ethnicity and immigration events. I have been on a billion boards. This is the most fun I have ever had on a Board of Directors. And we are actually raising the money we need.

After I retired I did the Radio show, Truth to Tell — a local public affairs interview show on KFAI. It has been fantastic, but I am winding that project down. Moving on….

Building on the Legacy

It is important to know how people struggled before you. In the ’70s, I didn’t know we had radical ancestors in the 1930s. They even had their own alternative schools movement in the Twin Cities. We were recipients of that legacy but didn’t know it.

The Southside neighborhood movement in the 70s worked on public control of power companies, opened free clinics, community banks, alternative schools, cooperative groceries, tenants rights. We campaigned against corporate development, started robust cultural organizations, and built community institutions, some of which continue today in similar or different iterations.

There are many similarities in the organizing strategies and goals of the 1970s and today. Rent control is again on the agenda. The city just bought out a slumlord, and groups like Inquilinxs Unidxs Por Justicia is organizing renters to take over other properties based on the same cooperative values we espoused. The inheritors of the Saul Alinsky tradition are Isaiah and Take Action MN. Other people are fighting for more worker control of coops. Millennials involved in DFL politics have taken up the mantle of the Farmer/Laborites for a grassroots political party, though many are not familiar with that history.

I do think South Minneapolis and the West Bank — relative to the state as a whole—has a progressive politics in part because of the work we did. Thank God young and incredibly creative people have taken over that work.