One of the crucial steps to untangling this web of mass incarceration is creating new pathways to literacy. So many of my clients learn how to read in prison. This is a real miscarriage of justice. It is difficult to help someone understand their indictment or evidence against them if they cannot read. I thought I had obligation to change that trajectory.When 85% of the population in the juvenile justice system and 60-80% of the adult prison population are functionally illiterate something has to be done. I decided to focus on promoting reading. We created a social enterprise: a bookstore and a nonprofit foundation to help produce diverse books and get them in the hands of children. This led to the creation of Planting People Growing Justice Leadership Institute.

— Dr. Artika Tyner

Isabel Wilkerson and My Family’s Migration to Minnesota

I learned about how my family ended up in the Rondo neighborhood of St. Paul from Isabel Wilkerson. She was doing a book reading and keynote address about The Warmth of Other Suns. We were casually talking. She is a powerful storyteller and historian. I told her that five generations of my family on my mother’s side have lived in Minnesota. I didn’t know why, just that they lived in the sacred ground that we call Rondo. She said, “Well, what type of work did they do?” I said my grandfather’s cousin initiated the move for everyone, and he worked for the railroad. She said, “What did he do?” I’m thinking, what does this have to do with our Rondo story? Before I could tell her, she told me, “I bet he was a Pullman Porter.”

My grandfather’s cousin, the Pullman Porter, brought his mother and his grandmother. That’s how we’re getting up to five generations. Eventually he and my grandfather helped everyone in their extended family, migrate north. They would go back routinely and bring a carload of relatives, some of them to Chicago, but many of them to Rondo in St. Paul. With a little math from her book, Wilkerson showed how my family’s story fit a migration pattern. Suddenly, with that short conversation, I knew more about my family history than I probably had explored throughout my whole life. It all made sense: and the value of kinship—when one person had an opportunity, they would extend it to the entire family.

Learning Radical Hospitality From My Grandmother in North Minneapolis

On my maternal side, my grandparents bought their first home in North Minneapolis. Growing up we visited my grandmother in her big yellow house every weekend, and whenever we could during the week. Our family had settled in this home by the late 1950s. My grandmother, Nellie Lightfoot, is a big piece of who I am. I was part of her faith community at her Baptist church. She was a role model and a guide for my life journey.

My grandmother taught me the importance of radical hospitality. If you knew Grandma Nellie, you knew the inside of her home. She would bring everyone over after church for dinner and building a sense of community. Her Sunday dinners were known all over the nation. If you were new to Minnesota, that’s where you went from a traditional soul food meal of fried chicken, greens, macaroni and cheese, cornbread, candied yams, and her famous yeast rolls.

My grandmother spent most of her life working as a domestic, cleaning other people’s homes. She had meager means but an abundance of faith. She taught me early on about God’s economy: whatever God called you to do he makes the resources available. With her mighty faith, she funded church mission trips and building funds.

She also taught me the importance of lifting your voice for justice. She was a professional gospel singer. She could have traveled all over the world but She chose to remain local and support her family and her community. At all the Baptist national conventions, all the awards they give, you usually see my grandmother’s picture.

My grandmother was everything to me. She had a massive heart attack and suddenly died on her way home from work when I was in 7th grade. Time stopped when she passed away. Of course, time still progressed, but everything else that happened in my life at that time feels like a minor detail because she was such an anchor in my life and in our family.

Growing Up in Rondo

Growing up in Rondo gave me a strong sense of community, of purpose, of culture, and of heritage. I spent Saturday mornings at Walker West Music Academy for my piano lessons with Reverend Walker and Mr. West. Growing up in Rondo meant enjoying the arts, community events, and going to church on Sundays. It meant being anchored in identity and having a strong sense of pride about being African American. I knew my cultural heritage and roots.

I came from a family of entrepreneurs. Before the freeway was built through the center of Rondo, there were hundreds of businesses in our community. Everyone built their own business and created opportunities for others. In my family that meant building businesses that responded to the needs of the African American community: everything from a tailor shop to a grocery store. They did that out of necessity because of the reality of Jim Crow. Racial segregation not only restricted access to jobs but also created barriers to shop as a customer. Fast forward to today, and we are building out of necessity in a new way. Today the Black community is asking, how do we build vibrant inclusive economies influenced by the principle of cooperative economics, ujamaa.

My family expected me to continue this legacy by opening my own business—a law firm. When I graduated from law school they were thoroughly confused about two things: one, that I never left the University of St. Thomas; I graduated in 2006 and fifteen years later I still work for the University. My dad was like, “Did you really graduate?” And two, “When do you open your law firm?” That question still comes up at family dinners all the time because I am one of the first in the family that worked at a traditional job. I am living out my grandfather’s dreams. He was told that he was ahead of his time, that he couldn’t become an attorney here in Minnesota and go to law school. He faced a lot of impediments to making his dream of becoming a lawyer come true. They say you are your ancestors’ wildest dreams. Here I am. I was able to go to law school and then continue to open doors for the folks who are coming behind me and beside me on this journey to racial progress. So, for me, it all really goes full circle.

Child Freedom Fighter

As a child I did not have a clear vision that I wanted to be a lawyer. One thing was for certain: I wanted to be a freedom fighter. I always was the one that questioned why things were wrong. I was the kid who thought her first name was Hush and her last name was Child. I credit my mother with having so much patience with me. Every social justice issue: I was on it. What are we gonna do Mama? How do we solve that?

In the early days, I didn’t understand how we address things like hunger in the community. I would just randomly invite people over to our house. Mother was like, “Who’s that? And I’d say, “I don’t know, I just wanted to make sure they ate.” If she gave me a gift, I would say, “Well the other kid needs it more than me, so buy two.” That was always just my nature. I was running book drives and book donation centers, years before I created our nonprofit. It was just who I was.

So, my first inclination was to turn to education. I’m coming from a family who are also teachers. My mother is an educator. My strongest skills are around teaching. When I’m in the classroom, I’m in my zone. I love to be able to inspire, to be able to motivate, to be able to create opportunities for people to learn and grow in some meaningful ways on their own terms, where everybody can have ownership of their learning process.

Though I’ve talked about Rondo in a sentimental way, the reality was that my high school years, were the peak of the war on drugs. There were some real challenges. There were drive-bys and violence. We saw things on our bus ride home that we shouldn’t have seen as kids. We were bound by this one-mile radius from Dale to Snelling. We were bussed down Snelling to Highland Park Senior High School. One of the safe places was the library or staying at home reading books. I always had a passion for reading, but I think that staying inside for safety, I read more books.

High School Mentors

I absolutely loved my high school teachers. Dr. Marvin Leonard Grays was my English teacher. He figured out that I enjoyed teaching others. I was quite the Chatty Cathy as they say. I think today I probably would have gotten referred out of the classroom into the juvenile justice system for disorderly conduct for talking so much. With the pervasive nature of racial stereotyping, there would be no way that I would be getting gifted and talented services or be propelled into the International Baccalaureate (IB) program today. I was just being myself, talking when it was not the right time or right place. Most teachers don’t know how to deal with it.

In Dr. Grays’ class we had many new immigrants, new refugees, our Hmong brothers and sisters, Ethiopian brothers and sisters. He taught me how to tutor our English language learners, teaching them English and literature. That was my first experience as a teacher. He turned what others would consider a problem student into a challenge and an opportunity. He opened a pathway for me, creating a school experience that was unique and customized.

I was part of the Chinese Immersion program in Highland Park. My Chinese teachers Li Lāoshī and Wu Lāoshī got me beyond the constraints of my own neighborhood. We didn’t just learn Chinese language—we learned culture. They brought in Ma Lāoshī , an expert on Chinese calligraphy, all the way from China. I won the Chinese calligraphy award. So, when I was young, I was already imagining traveling and living around the world.

Mrs. Charlotte Landreau was my history teacher. She was the one that gave me a world-class education. She sparked my interest in living, working, and traveling around the world. And she also made college possible for me because I was a first-generation college student. She graduated from Macalester, so she said to me, “We should go on a tour to Macalester.” She got me the application. She talked about it so much to me that it made it customary. Of course. I’m going to Macalester, like Mrs. Landreau. She made me feel like I was already there.

The best teachers are treasure hunters. My teachers helped to discover treasures in me I didn’t know were there. Recently my mentors from Highland Park invited me into their monthly lunch club for retirees. That was one of the best invitations I ever received in my life.

College at Hamline

I wanted to go to Macalester like Ms. Landreau. I got in, with an academic scholarship, but they had one criterion, that you had to live on campus. I remember thinking, I’ve never left home, and I just wasn’t ready for that. So I went to Hamline, which was a close commute from home. While I was still a freshman, I got a job tutoring at the writing center. It was open to both undergraduate and graduate students. I thought, “Are you sure this job is for me?” But the director saw that I had a passion for writing. She discovered it before I did. I knew all the rules of grammar and punctuation but I didn’t know how to explain the “why.” I learned so much about teaching as well as writing, at the writing center, and that job has much to do with why I do both today. I began tutoring at Hamline, and working as a student journalist on the Hamline paper, The Oracle.

I started at Hamline in 1999. I just thought I needed to take classes and do well. The start of my second year I got this letter, it said, you’ve never declared a major. Based on my high school transfer credits (PSEO, Full IB Diploma), I was already a junior. I added up credits and became an education major. But by the end of my time at Hamline I was leaning toward law school.

Going to College With My Mother

My mother spent most of her life in roles as secretaries or as a domestic, working with my grandmother. While I was going to law school she went to college, at the age of 50. When I earned my doctorate, my mother finished her master’s degree.

Pivoting to Law School

My experience as a student teacher compelled me to go to law school and become a civil rights attorney, working on racial disparities in education and criminal justice. Many of the things I’d seen as a child in Rondo, I was seeing more clearly in the classroom, but I recognized that the issues I wanted to address were systemic. I knew law was the language of power, so I told myself, let’s get well versed in this language so I can do more in the community.

It didn’t hurt that Hamline had a law school right there and they had a dynamic professor, Robin Magee. I couldn’t help but be inspired when I heard her speak. This talented powerful African American law professor was changing systems and changing the world. She was working on two issues that I recall: policing reform and increasing the diversity of jury selection, two big issues that we still need to work on today.

The Essential Mentorship of Professor Nekima Levy Armstrong

I went to University of St. Thomas Law School. There I met this dynamic professor, Nekima Levy Armstrong, who was my moot court coach for the national Black Law Student Association. That was providential because the topic that we had for moot court was the racial disparities in sentencing for crack versus powder cocaine. In a sense, working on this issue took me full circle. Growing up, I saw the discrepancy between what people thought “the war on drugs” was, versus the actual experiences of my family members and community. People were sent to the prison gates for nonviolent drug offenses. The system treated substance abuse as a crime, not a health issue. It compounded the disparities when it sent people back home, reentering society with a permanent scarlet letter that read “felon,” prohibiting access to jobs, housing, and the ballot box.

Law school needs some major transformation. Representation matters. Inspiration matters. To see another powerful black woman at the forefront of social change was crucial for me. I didn’t meet Professor Levy Armstrong until my second-year law school. I only wish I had met her sooner. I was convinced I didn’t belong in law school. I did not see anyone that looked like me: not on the faculty, not staff, or students. The classroom experience was isolating due to the presence of microaggressions and racial stereotypes. I even started losing my passion for working on civil rights and human rights issues.

I remember on our drive back from a moot court competition, Professor Levy Armstrong asked me what I was passionate about. No other professor had asked me that or even spoken to me on a personal level. We were driving back from Wisconsin, and she spent hours talking to me about unpacking my passion and letting my career journey align it. I got out of that van that day, still not convinced that I had too much to add as a future attorney, but I enrolled in her family law clinic and the rest is history. She encouraged me to apply for a teaching fellowship. I ended up working as a teaching fellow under her mentorship for six or seven years. And now I am still at St. Thomas, teaching.

The Community Justice Project

In 2007, we launched a pilot of what today is the award-winning Community Justice Project. Professor Levy Armstrong had a vision of creating a civil rights clinic within legal education that had never really had been done before. Most law clinics work with individual clients; we were taking on the whole system. It was unheard of. We were combining law and public policy to create large-scale systemic change. We became an inspiration for other models of community justice projects that have been adopted across the nation and around the world. The average clinic probably serves six to twelve clients per semester—perhaps an immigration case, a family law case, or an elder law case. The Community Justice Project said if we’re going minister to the needs of clients, we don’t have the capacity to fill community needs. Instead, let’s get to the root cause of the issues and fully transform and change the system of inequity. We can alleviate some of the issues our clients are facing.

Racial Disparities in Charges of Obstructing the Legal Process

The first project that I worked on under her supervision was addressing the racial disparities in Saint Paul in charges of obstructing the legal process. We found there was broad discretion given to the police. At that time there was a dramatic increase in charges of obstructing legal process (OLP), impacting, primarily, communities of color. Here is how it often worked: If an officer was performing an arrest and I observed it and said, “what’s this all about?” I could get charged with obstructing legal process. We worked on increasing the specification of actions that could be defined as an OLP and helped to create restorative justice circles to deal with some of the issues associated with the racial disparity in these charges.

Reforming Gang Database Policies

We also worked on reforms related to gang databases. In Minnesota you could face enhanced sentencing for being on the database. Someone could be in database for being associated with a relative or writing a letter to someone on the database. The databases were filled with young men of color thereby creating a pathway into the criminal justice system. We worked on raising awareness around the need for more jobs for young men of color in this tangled web of mass incarceration. How do we create more jobs, education, and professional and personal development opportunities?

Our work transcended anything that anyone had thought about at that point. We transformed clinical legal education from a focus on direct client services to addressing the magnitude of multifaceted social justice issues.

Institutional Racism and Excellent Pedagogy in Higher Education

I recently posted a piece on higher education. Since I entered college 22 years ago, we still have not increased institutional diversity. We need representation at all levels. We also need educators who are treasure hunters, committed to finding the passions that students may have, and cultivating them in meaningful ways, like Dr. Grays and Prof. Levy Armstrong, did for me. That is what I think about when I teach: how do I help my students discover their gifts and talents in tangible ways?

As a professor, I have to make sure that I’m engaged on the issues that are happening in real time. I can’t get lost and say it’s only the issues that happened in our case books that matter. One of the things I do at the end of the semester is a community presentation. We take those current issues and teach them to the community—how to impact administrative agencies, creating a little bit of that same experience I had with the Community Justice Project.

Last year, my students worked on looking at how administrative agencies were impacting civil rights issues. At the peak of COVID 19 we saw how racial disparities increased. What was the role of the CDC? How do you address racism as a public health issue? We also looked at voting rights. It is shameful that in Minnesota we are still talking about whether there should be felon disenfranchisement when we know, based upon the research, that voting is a positive pro-social activity. We know that people who are on probation and parole, living here in the community, are part of the tax base. Why would you not want them to be part of something that helps to support community health and well-being?

2020-2021: Investing in My Freedom Journey

This period has been personally and politically exhausting, but exciting and exhilarating at the same time. Exhausting in the sense that initially I took on the burden of trying to teach everyone. I got this message, time and time again, from white allies, white brothers, and sisters: “George Floyd was killed and murdered, and I finally see race. Teach us what it’s like!” What does that even mean?

Initially, I took that burden on. Then I woke up one day and thought, “Why am I trying to teach friends, other faculty members and colleagues when they should be developing their own core competencies?” I literally cut and paste the same email, and sent it to everyone, so they would stop asking the same questions and making the same requests to teach them and help them to understand racial justice.

If I meet you in the classroom that’s different, but on my personal time there’s no way that I’m going to do your homework plus mine. I do my best to inspire my students, to create and foster a learning environment. I love what retired Minnesota Supreme Court Justice Alan Page says: we are the foremothers and forefathers of the future. Today we are writing the chapters for the future. I take on that responsibility. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for.

So when I say “exhausting,” it is because I don’t think a lot of people wanted to take on that level of accountability. That work belonged to them and not me, but they were like, “Can you lead the racial healing circle?” No, no. “Continue to teach us?” No thank you. We are each responsible to do our own work—daily action to become antiracist.

Times are exciting, because saying no allowed me to lean into myself in ways that I had never done before. Once I freed up my time—once I was not responsible for someone else’s trajectory, their pathway to anti-racist practices, or to their ability to challenge their own bias stereotype and prejudice—I started writing more. I focused on my own cultural experiences. I bought a ticket and went back to Ghana this summer because I wanted to understand how art influences cultural history, preservation, and cultural and community development

I started recharging and renewing myself for the long journey of freedom ahead, and that’s when it got exhilarating.

Accra, Ghana, 2021

Traveling Home to Ghana

My first trip to Ghana was in 2016. It had been a goal on my vision board for a decade. So much of our culture—the history of civil rights, the future of Pan Africanism, being united under that that Black Star, a sense of the African diaspora, knowing who we are and knowing what we can do collectively—comes from defying the myths about Africa. The only things that were taught about Africa is starvation, chaos, and wars. That’s not Ghana. That’s not Africa. So, for me, traveling back to Ghana was about purpose and identity.

I had a dynamic young emerging scholar named Monica Habia. She was in my policy program. The whole time she talked about traveling to Ghana. I thought to myself, OK this sounds interesting. I didn’t think I could afford a ticket, and even if I did, I wouldn’t know what to do, but I continued to engage her, the same way my professors engaged me. I said, keep writing about the issues you’re passionate about it. She was passionate about women’s empowerment in girls’ education in Ghana. So, one day she said, “I’m going to write a research proposal. I said “You go girl!” I didn’t realize she was going to include me in her research grant to come along with her. She came in the office one day and said “I got my research grant. Pack your bags.”

Her passion area eventually became a part of my research. I have been there a dozen times since. I’m working on a research project now on the role of African women leaders in shaping social change. In Ghana it’s radically different from how we think about leadership here in the US. Ghana is a matriarchal society. Women play a very active role in political, social, and economic dynamics.

Working on this project has given me to a new sense of purpose and determination because now I realize that my work is a part of a trans-global movement for justice, for equity. In many ways the quest for African Americans is always to find home. Paul Robeson sang Sometimes I feel like a Motherless Child so far away from home. We’re still grappling with home and identity today.

Ghana gave me a homeland. Since then, I’ve been following the journey of the synergy around Pan-Africanism and the civil rights. Dr. King wrote a sermon that he delivered when he came back from Ghana on a birth of a new nation, and he talked about some of the lessons that we can learn from the global Black liberation movement about heritage, about unity, about economic independence and how Ghana was able to do that with their first under Prime Minister, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah. Malcolm X spent time in Ghana. So did Maya Angelou. Ghana is the resting place, the final home, of Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois. Every time I go I think about how those pioneering heroes and sheroes also came on this journey to understand our connection to land.

2019 Community Trip to Ghana: Year of Return

In 2019 something magical happened. I just posted on Facebook: “If you want to come to Ghana with me, I’ll be there for The Year of Return.” President Nana Akufo-Addo, speaking at the UN, had announced an invitation for 2019. No matter where you were from in the African diaspora, he said you are welcome to come home. I thought he was speaking to me, and others felt the same way, so I opened the invitation. I didn’t know who would show up for our info session. Primarily it was all my elders who signed up. Mr, Khaliq and Miss Vicky Davis, NAACP leaders, signed up. Mr. Russel Balenger from Circles of Peace, showed up. Titilayo Bediako, of We Win Institute said, “I’m coming!”

What happened on the trip was that intergenerational sense of finding identity and direction. I didn’t realize until we got to the slave castles that many of them had waited their whole life to travel to Africa, but they didn’t know how. They all said they trusted me to take them on the journey. That was one of the greatest accomplishments of my life—and I have national and international awards. I have trophies getting all dusty. I helped someone else take them on a journey for their life to go full circle. Now I am making a documentary on the trip.

Writing Children’s Books

One of the crucial steps to untangling this web of mass incarceration is creating new pathways to literacy. I was angry about the fact that so many of my clients learn how to read in prison. This is a real miscarriage of justice. It is difficult to help someone understand their indictment or evidence against them if they cannot read. I thought I had obligation to change that trajectory.When 85% of the population in the juvenile justice system and 60-80% of the adult prison population are functionally illiterate something has to be done. I decided to focus on promoting reading.

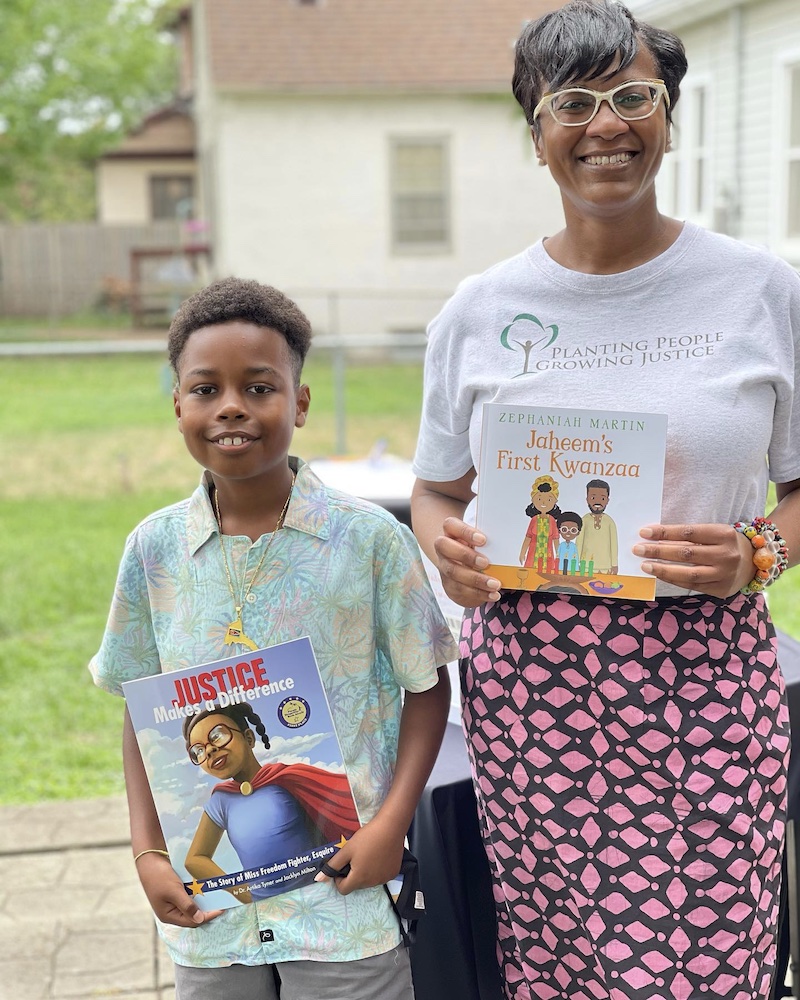

Here in well-resourced Minnesota we have book deserts. There is also the problem of representation in the literature. When I grew up, I didn’t have any books with characters that looked like me. You’re more likely to find a book with a black dog or a black bear on the cover than a book that features a Black girl or Black boy. My team decided to take action and lead change. We created a social enterprise: a bookstore and a nonprofit foundation to help produce diverse books and get them in the hands of children. This led to the creation of Planting People Growing Justice Leadership Institute. We are celebrating our fifth year. At our annual youth leadership summit, we have a book giveaway. We make it a fun carnival, with learning activities, making sure that we’re promoting reading for children of color and for all children. We also have book giveaways throughout the year.

This year we’ve also launched writing competitions for youth. I am so proud to announce just last month we had our first winner of our youth writing competition. Zephaniah Martin, who is only ten years old and wrote an amazing book about Kwanza, Jaheem’s First Kwanzaa, which ended up being an Amazon bestseller.

Our book Justice Makes A Difference has gone further than I could have imagined it: from Nigeria to Cuba to Jamaica—the book is everywhere. We’ve donated over 7,000 diverse books, reached over 5,000 young people with our lectures in school. We achieved these milestones by using my grandmother’s lesson about God’s economics, God’s math: whatever it takes. When I said that we need a more diverse books major publishers basically made it seem like people of color couldn’t read and didn’t have the disposable income to purchase books, or even sense enough to know that we needed them. They insulted me enough to make me create my own publishing company and take action. We won the inaugural Community Creates Award for creating a book that helped to celebrate community and address a social justice issue.

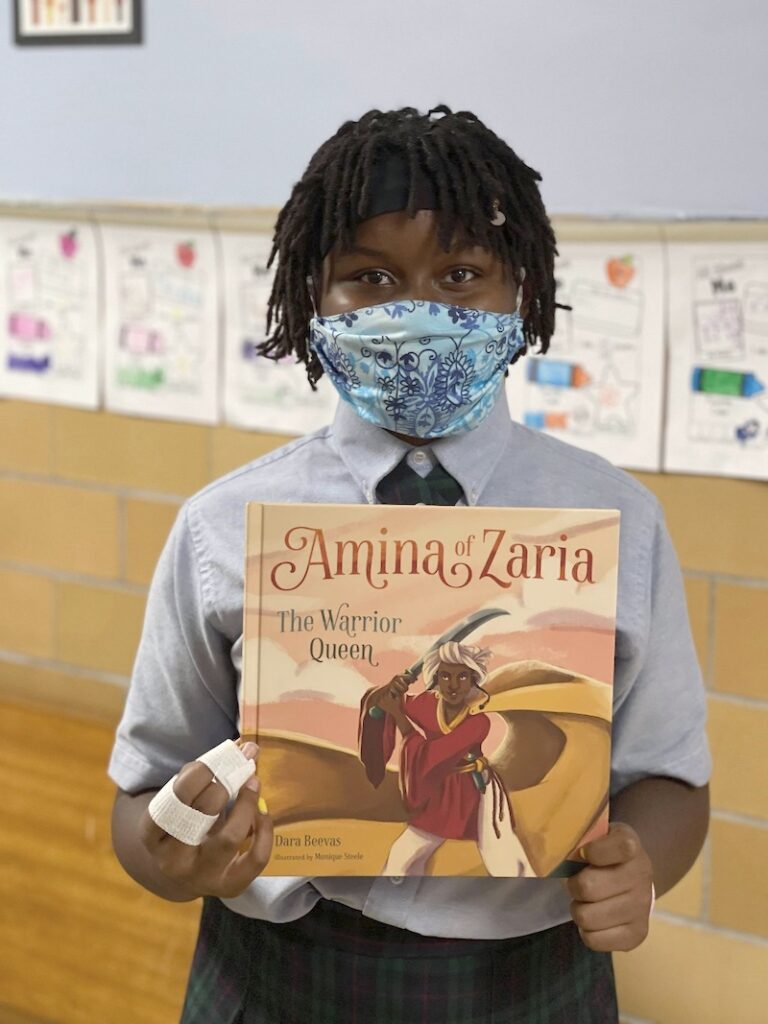

I’m writing the stories I needed and didn’t have when I was younger. Not just characters but also stories I can relate to. They threw Jessica into the Babysitters Club or one random character into Sweet Valley High, but now I’m delivering my young niece a book about Queen Amina (by Dara Beevas). Now she can see herself in the books I write and promote. This is what social justice in action looks like.