I have been sharing my story since the death of George Floyd and the start of the Minneapolis Uprising. It opened up all of my wounds that I have been experiencing all my life. This is the first time I felt valued. It is the first time I feel like people are listening and people want to help.

— Kenneth Holt

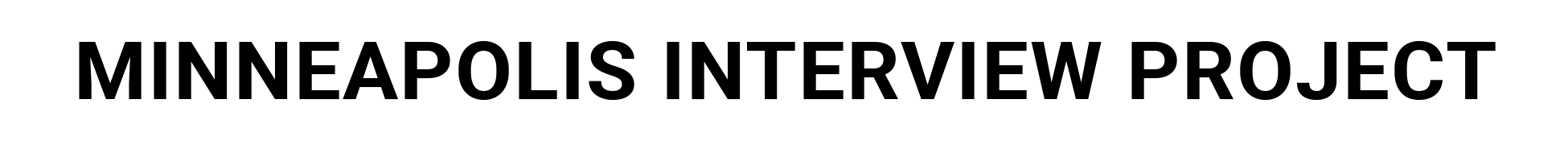

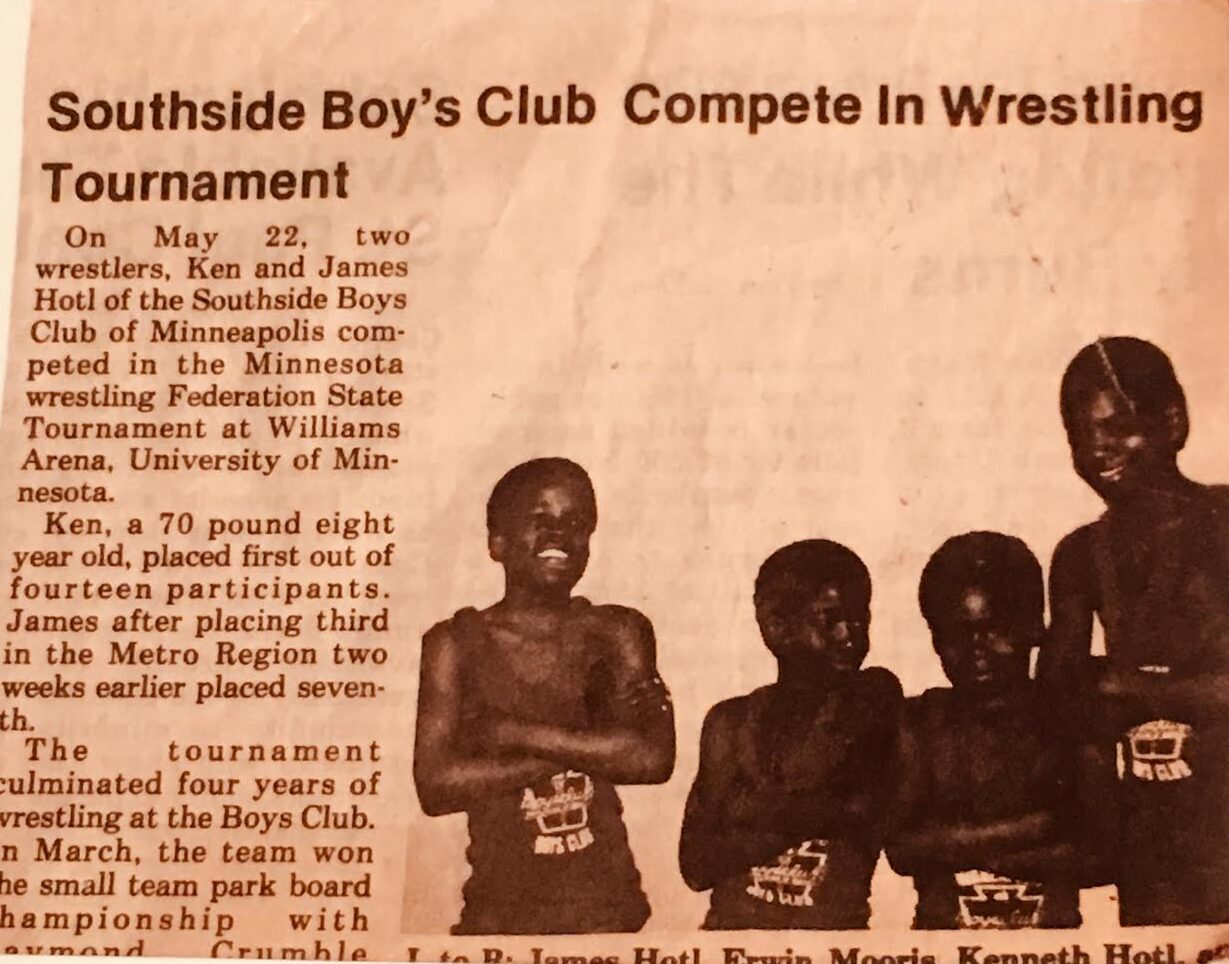

Self-Worth and Discipline at the Boys Club in South Minneapolis

I went to the Boys Club in South Minneapolis from age six to thirteen. Through them I was able to participate in every sport, including wrestling, which I was good enough at that I competed nationally. When I was growing up, the Boys Club was over on 38th and 5th. After ten years it moved to 36th and Chicago, into an old funeral parlor. I think there is a limited Boys Club program at Phelps Park today, but nothing like it was when I was little. The Boys Club was great for me. Sports taught me discipline. I lean on those skills I learned there today.

Growing Up in Bryant Neighborhood, When it Supported Black Businesses

I grew up in the Bryant Neighborhood when there were a lot of Black-owned businesses. That was something that resonated with me. On 38 and 4th there was Mr. Rubin’s grocery store. He also had a game room where we played video games. The building was torn down and now it’s an empty lot. Across the street, Mr. Crown owned a record store, a barber shop, and a beauty salon—now a fire station stands where those businesses used to be.

Where George Floyd was killed, 30 years ago that was Wilharms Drugs, and across the street was the 7-Eleven where we bought our Slurpees and Big Gulps. Going west on 38th Street—where Sabathani Community Center is now—that used to be Bryant Jr. High, where my older siblings and Prince Rogers Nelson went to school. Across the street, where the Seward Coop is now, that used to be our church: Greater Friendship Missionary Baptist Church. They relocated east to 26th and 38th.

There were other significant business landmarks in the Bryant neighborhood that were not Black-owned, but Black families patronized these businesses and felt welcomed and appreciated there. Going west, on 38th and 3rd was an ice cream parlor called French Quarters. They also sold chicken wings. You could get a two piece and a roll for three bucks. That was very affordable for people living in our neighborhood.

On 38th and Nicollet where the hardware store is now—that used to be a bowling alley where we used to bowl and play video games, etc. Going north on Nicollet: Art Song’s Chicken was on the corner—everybody over south knew that Art Song’s was the best place to get wings. There was also a bakery right next door; we used to buy cookies and doughnuts for a nickel and a dime. The owner was so grateful to us. Every day, after they closed, he put out the danishes he didn’t sell, for us to take for free. These are things I will never forget. Right across the street was O‘Tooles Drug store—this was a community store that a lot of us went to, down on Nicollet. Of all of the business I mentioned, Finers Meat Market is the only one that’s still there today.

A System that Policed Poverty and Criminalized Black Boys

My interaction with the police began at a young age. When I was about eight, they were giving me football cards and greeting me—generally our interactions were positive. By the time I was ten, I became a threat. There was this police officer, Jim Dale, who worked at Phelps Park on 39th and Chicago. The Boys Club didn’t have a football field, so we played at Phelps Park. Jim Dale used to terrorize our neighborhood. He made us feel uncomfortable living in our neighborhood, being a kid. This is where a lot of my depression and trauma started.

I grew up in poverty. My father wasn’t living in the household. He was somewhat a part of my life, but I missed out on not having the disciplinarian and the leadership of a consistent male figure in my life. My mom was a strong Black woman. Taking care of six kids by herself, she taught me my work ethic. I started working at the neighborhood corner store when I was eight, pouring bottled water over Mr. Rubin’s collard greens so they wouldn’t get dry. I also swept up hair at Mr. Crown’s barber shop.

I had trouble in school. I didn’t like the teachers or the system that was educating me. I went to many different schools: Laura Ingalls Wilder, Bancroft, Standish, Anderson, Northeast Jr. High, Anthony Jr. High, Roosevelt, Washburn, Street Academy and Work Opportunity Center (WOC). I was really disappointed when they tore down Central High School in 1982; like all of the other kids in my neighborhood, I was looking forward to attending there. Everyone that I looked up to went there, and they had a really good football team. I ended up going to Roosevelt my freshman year, but they kept transferring me because I was getting in trouble.

When I was eleven—a little tadpole—one of my teachers at Bancroft told me I would “never be shit.” That affected me tremendously. I kicked her, ended up getting an assault charge and went to juvenile detention. I started branching out. I was gang affiliated by the time I was thirteen—a product of my environment.

I started smoking marijuana at age six, had my first drink at age eight. I was drinking 40 ounces in the alley before high school. I self-medicated to deal with my environment. As an adolescent I had seventeen felonies, all for theft and assault. In my neighborhood you were either going to be a victim or you were going to be victimized. Because I refused to be a victim, I started victimizing. That was what led me to getting all of those felonies. All of my dreams of being one of the best athletes in the world went down the drain.

County Home School

I was 15 in 1988; this was the time when they had the bulldozers on 4th Ave and 31st—they called it Crack Alley. This is when so many of my friends and family were strung out on drugs, unable to quit. That year I was involved in robbing a pizza man with some of my friends, and as a result I went to the County Home School for 4-6 months.

Sometimes, you have to change your surroundings in order to change yourself. The County Home School in Minnetonka was a rude awakening for me. For the first time, I was able to self-reflect. I asked myself, is this who I truly am? I began to start making a change. The program taught us discipline; on Saturdays we had to do super-cleaning. They would go around with a white glove and if there was dirt on the glove then you failed and you wouldn’t be able to participate in any of the Saturday activities. Saturdays were fun-filled. They had horses and they taught us how to ride them and clean their hooves. We could play football and basketball. They had group therapy to talk about the things we were going through and what was bothering us, so things didn’t build up like a volcano. All of these things helped me become the man that I am now.

The program was pretty good, but I can’t give them more credit than I give myself. I had friends who went through it, who were not able to make the changes I was able to make. They became institutionalized, leading them eventually into prison. I was released at sixteen and was able to go back to high school and graduate on time, from Roosevelt High school.

The Trauma of having a Friend killed by Police

George Floyd was not the first time I saw a brother killed by the police. In February 1992, the cops answered a call about a domestic on 35th and 5th. Ted Bobo and his girlfriend got into it. The police shot him several times and killed him. I was nineteen at the time. Ted was 24. This was a person we knew. This was a person who went to the Boys Club. This was a person we looked up to. For it to happen, the way it happened, for us to not get any counseling or therapy, to get the help we needed—that was traumatizing. A lot of us felt “What is there for us to do?” That was the start of what was to come. The norm for people who looked like me.

I had another police encounter after high school. Janeé Harteau, (the former police chief) and her partner—we called them Cagney and Lacey—would sweep through our neighborhood and harass us. In one incident that I remember, my friends ran from them because they had drugs. I didn’t run because I didn’t have any. Harteau roughed me up, put me on the car and called a K-9 unit. I swore at her. She put me in the police car with the dog growling at me. I passed out and woke up when we arrived downtown. They kept me overnight, released me with no charges the next day. When I see situations like the killing of George Floyd, all these other traumatizing events come back.

Advocating for Kids At Bloomington Kennedy High School

After high school I had a job working for Marsden Maintenance, and then Federal Express. When I was 23 years old, in 1997, I began working at Bloomington Kennedy High School. At first I started working security. It was one of the best things that could’ve happened to me. I noticed a lot of kids going through similar things that I went through. Now I was able to give back in a way that was really touching—not only for them, but for myself as well. I still have some of those relationships from those first years.

I have worked with Bloomington Public Schools for 24 years. Today I am a “Para”—a Teacher’s Assistant for Special Ed students. I have been at Bloomington Kennedy High School for all but one year. Kennedy was a “white boys club” when I first got there

—in terms of the teachers—and I wasn’t invited. Despite this, I was feeling really good about my new job reaching out to the kids.

I was transferred seven years ago, for one year, to Jefferson High School. In Bloomington, Jefferson is the rich school, and I didn’t want to work there. I didn’t feel there was a need for me there. There were more kids who came from poverty at Kennedy. For one year, it was a good experience. Many of the Jefferson kids looked down on the Kennedy kids, calling them ghetto, etc. and the Kennedy kids called the Jefferson kids “siddity” and entitled. I was able to share my experience with Jefferson kids, and bridge the gap with the Kennedy kids when I returned there.

I tell my students two things: 1) I have a Ph.D. in my mistakes—nobody can explain my mistakes better than me; and 2) Regardless of how long it takes, it never says how long it took you to get your diploma. With COVID, our new normal is hard on the kids I work with. A lot of them work best in brick-and-mortar learning environments and online learning has been difficult and troubling for them. We are living—and learning—in ways we never did before. People are perishing from the pandemic. The George Floyd situation makes for even more uncertainty. Not all the students know how to ask for help to deal with all of this, and often they ask for help by acting out. I was that kid. I also didn’t know how to ask for help. I also acted out. So I can help them, assist them. That is wonderful to have that know-how, to share that experience and give back. That is what led me to create my own organization: Our Future Leaders Mentoring & Consulting. When I was at the Boys Club, I knew that someday I would do something like this.

Surviving Too Many Losses

I began at MCTC in 2009 and got my Associate Degree. I started at Metro State, working on my bachelors, but then I went through a rough period. I lost ten people in seven years. I lost two nephews, three close friends, two uncles, my grandmother, my two-year-old son, and my mother. I had been taking care of my mom, helping her with her dialysis. Her illness and then her death, the death of my son, on top of all the other losses, was too much.

I didn’t want to live anymore. I didn’t want to be around anybody. I didn’t know what to do. I started self-medicating again. But then I started using the discipline I learned from the Boys Club. I began working out. Five days a week I walk a 5K around the lake, do six hundred push ups and six hundred squats. I also started going to Common Grounds to meditate, which really helped. And I was able to get counseling through my job. There were two parts to my counseling: one dealing with my losses, and two, dealing with all the trauma of growing up Black in this city that is top in all disparities—growing up without a level playing field.

This has been tough. Very tough. I’m blessed to say this is the first time in my life that I have been drug and alcohol-free. I didn’t go to a facility. I did it out of my own free will. This is the discipline I learned as a child. I quit smoking cold turkey in 1991. I thrive by finding a way out of no way. That’s me.

Breaking down Barriers Since the Murder of George Floyd

I still live in South Minneapolis, in a house I bought in 2009. I have five children. This is my home. I have been sharing my story since the death of George Floyd. It opened up all of my wounds that I have been experiencing all my life. To see a man killed like that, by a man with his hands in his pockets and not a care in the world. Out of all the states, out of all the cities, It happened in my state, in my city, and in my neighborhood.

It was breathtaking to be able to—if you want to say—start a revolution, from my neighborhood, going all around the world. I have seen a lot of former students who are part of the protests, and I am impressed. I didn’t have the courage to be a part of something bigger than me when I was their age. But now they have a movement to join. Now being a part of a social justice movement is pushed as the right thing to do. Before, you were criticized. Just a few years ago, Colin Kaepernick was doing the exact same thing and he was looked upon as a villain. Now he is looked upon as a visionary, which he should have been all along. Kaepernick’s narrative was never about criticizing people who served our country, it was about the injustices at home.

To me, Black Lives Matter is not a movement. It’s my life. As a Black man, this is the first time that I felt happy about white people, being on the front lines with Black people, in solidarity, putting their white privilege on the line, putting their life on the line to listen and understand. This is the first time I felt valued. It is the first time I feel like people are listening and people want to help. It makes me feel real good, because all my life I have been saying these things but people weren’t listening. Now I have a platform to be able to share my story, to be able to help people understand. I have shared my story at the “We are All George” Rally at the Commons Park Downtown, on Saturdays at the Bryant Neighborhood Organization, at the Bloomington March for Justice, and at a healing session where I was interviewed by Channel 9 news. Every time, I see people in tears.

You only know what you know. Sometimes if you’re not affected personally, you are just not going to understand. For whatever reason, George Floyd affected people to their core, and forced people to understand.