So often power comes with negative connotations. I became conscious of how important it was to create a situation that empowered artists. I never auditioned anybody to perform in Patrick’s Cabaret. There was one requirement: you had to see a show before you could be in one. Without auditions, artists didn’t have to think, “What would Patrick like?” They could think, “What do I want to do?” As an artist I knew we create our most interesting stuff when we follow our own muse.

— Patrick Scully

Roots in Rural Minnesota

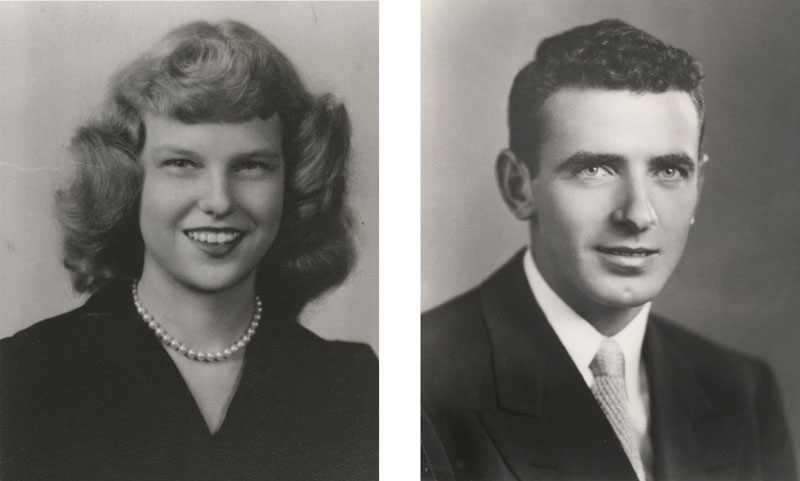

My mother grew up in Worthington, in the southwest corner of Minnesota. My dad was from Slayton, north of Worthington. They were part of that generation’s big migration of European Americans who moved from rural to urban or suburban settings for their adult lives. I grew up in Roseville with one older brother, three younger brothers and one younger sister.

Growing up Catholic in Roseville, Minnesota

Our neighborhood of Roseville was split 50-50 between Catholics and Protestants. Catholic kids like me went to St. Rose of Lima from kindergarten through 8th grade, surrounded by the same kids for nine years. I was there during the Vatican II change. One day we were being taught by nuns in black habits and the next we came to school and they were wearing clothes from the 19th century – a zoom forward by a few hundred years. I would say that the staff at the school was 55% nuns and 45% non-nuns. Every day at the end of the school day the PA system played John Phillip Sousa’s: Stars and Stripes Forever. Whenever I hear it now, I think “time to go home.”

We went home for lunch in the middle of the day. If my mom was working, my siblings and I would get our own lunch together. It was a very insular, suburban reality. We didn’t go to Minneapolis or Saint Paul with any kind of frequency. Occasionally we might ride our bicycles as far as Como Park.

My transition from Catholic schools to public schools happened in 9th grade: Fairview Junior High School. lt was an awkward time to arrive. The rest of the kids at the school had been there for 7th and 8th grade and so I found myself at a loss socially, on the outside looking in, wondering, where do I fit in? I remember thinking, “When I finish high school I want to be known and recognized among my peers. I don’t want to ever feel like an outsider again.”

Feminist and other Social Movement Influences in High School

I was in high school from 1968-71, so even though I grew up in a very conservative and Republican family I was influenced by the attitudes of the times: the anti-war and civil rights movements. The sense of the youth was that the people who were running things were not doing a good job and we needed to change the world. I was also aware of feminism; the way feminist thinking was reshaping how we understood ourselves and our culture. The kids I hung out with in high school weren’t activists, but they were smart enough to be aware of what was happening in the world.

In high school there were these days when we cancelled all the regular classes and took suggestions from the student body on who should be invited as guest speakers for the day. We got the lesbian English Professor, Toni McNaron, from the U of M. I remember her saying it was hard to teach Shakespeare when you know people running this country are telling lies. She talked about the importance of telling the truth, even when leaders don’t. She was impressive.

The vice president of the student council when I was a junior, was Barbara Jean Metzger. She became very much involved as an out-lesbian in her adult life in DFL politics in Minneapolis. It was whispered in high school that she had a girlfriend, and I was aware of malice behind those kinds of whispers.

It was during high school that Stonewall happened. I knew about it vaguely, though I don’t know how. And I was aware, from the mass media, of voices like Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan: second-wave feminists.

There was a student who always sat behind me named Barb Schumer, (we were put in alphabetical order). I remember her telling me about this gay rights group, FREE, at the university that she thought I would be interested in.

Going to College on a Golf Caddy Scholarship

I decided to apply to the University of Minnesota. It had been my plan and expectation all along. My dad had told me when I was in 7th grade that he expected that I would go to college, and that I would have to pay for it myself. He had too many kids to be able to afford to send them all to college and so he didn’t want this to be sprung on me as a surprise. I took it seriously and began working summers at the golf course. They had a program called Evans Scholars that was a scholarship program for people who’ve been caddies. I decided, well this seems like a good bet.

I got the caddy scholarship. On the surface it was a great deal, but it had some strings attached. They paid your tuition every quarter and provided you an affordable place to live in the Evans Scholars House, but if you didn’t live there, they would kick you out of the program.

Many of the Evans scholars were kids from middle-class and working-class backgrounds who liked to pretend that this was a golf scholarship; that we were an elite fraternity. There was this pretense around who we were and how we should behave. The other men were much more conservative than what I was used to. And their social rules were different. Among my peers in high school, if we were having a party, you invited everybody. If we wanted Tom’s girlfriend Kathy to come, you invited Kathy. At the Evans House, you were expected to bring a girlfriend, like we were back in the 1950s.

There were Evans chapters around the United States and every year they would get together for a big winter gathering in Chicago. Each chapter was supposed to send a representative, a “sweetheart” to represent the chapter. At one point I raised my hand at our Monday night meeting and said, “I think we should send the first male sweetheart to Chicago.” The meeting got really quiet. I continued. “We talk about the value of democratic representation. Let’s face it, there are now some girls who are getting Evans scholarships and there are probably also some gay men. We should send a male sweetheart to Chicago just to show that we are supportive of this social change.”

I was out to myself by that point, but I was not out with them. It was clear to me that that would not be safe. To make the Evans House a safe place for me I constructed a persona; I was as radical as Abby Hoffman. It helped if I didn’t want to participate in X, Y or Z. They wouldn’t bother to ask me. This gave me the space to be myself, which was important.

Every quarter they changed rooms, and we changed roommates, so we’d finish finals and then shuffle into some other room and get used to somebody else’s idiosyncrasies. I’ve often wondered what it would have been like to go to college living someplace that was supportive of who I was, where I didn’t have to spend so much psychic energy negotiating my way through. But there were moments where I felt like I was helping to change the mindset of the organization.

One day I came home from class and this guy, Pat McGee says, “Hey Scully come on shoot a couple baskets with us. We’ll play a game of horse and if you win, I’ll get you elected Athlete of the Year at Evans House.” It was like a Disney movie. I threw the basketball at the hoop and it went through! I threw it again and it swished again! I threw it every which way, and it kept going through. It was like the universe was making sure I won this game.

When it came time to elect the athlete of the year, I was one of two finalists. McGee argued, “He takes all these dance classes and that’s really a kind of athletics, and we should elect him for his athleticism.” Nobody was really buying it, but McGee was able to cash in on his social capital to make it happen. A guy who was a year younger than me, who played on the intramural football, hockey, and basketball teams was enraged that this dancer won athlete of the year.

There were moments like that; sort of minor triumphs, where I felt like I wasn’t just swimming upstream, that there was something to be enjoyed in the process of the struggle.

The Evans Scholars had a faculty advisor: a staff person on campus who the Evans organization probably paid an additional stipend to make sure that everything between the program and the university was in step. We only saw him once or twice a year when he’d come to a chapter meeting. He worked in the financial aid office. For me that was a red flag. When I heard that a couple guys had gone to see him and he got them some extra financial aid, I decided that I would apply. I was working part time. If I could get a grant, that would make going to school easier. I applied and got an additional grant. I made an appointment to go in to talk to our adviser because the financial aid office had a policy that they could give you no more in grant money than you got in loans. I was just getting a grant, no loan.

I had a small tape recorder in my backpack. I turned it on when I went to talk to him. I anticipated that he would say something incriminating. I told him I was surprised I was able to get all grants and no loans. He said, “I have the job in financial aid. I’m like a parent, or a grandparent. I can look the other way and help Evans scholars out.”

I called the Evans scholars headquarters in Chicago and said that I wanted to talk to the program director. This guy had no idea who I was. They said, “We’ll see if he can get back to next week.” I said, “I’ve got information that I want to talk to you about it. If I don’t hear from him by tomorrow morning at 10:00 o’clock I’m going to the Minnesota Daily with it.”

Eight o’clock the next morning he called. He flew to town that day to meet with me. I said “Having a faculty advisor who works in the financial aid office smells like corruption to me. I want to have a policy statement from you and the board of directors of Evans scholars around this conflict of interest.”

My stomach was churning as I spoke, but I thought, this is the right thing. Some of my motivation was about retribution. Some of it was that I didn’t like a lot of about how the organization operated. I ended up not going to the Minnesota Daily with the story. I didn’t even play the tape. I just told him I had this conversation and he believed me. He wasn’t surprised.

Discovering Dance at the University of Minnesota

I was majoring in biology, planning to go to medical school. There was no dance major, then but we had to have a certain number of phy-ed credits, and I filled them with dance classes. Someone had suggested modern dance to me. “I think you’d really like it.” Modern dance classes were hard to get into, but spring quarter of my freshman year I had first-day registration, so I signed up for my first modern dance class.

When I was in high school the coaches were former GIs who ran their teams like military squads. Among my friends, athletes were considered dumb jocks; we called them sporties: a term of derision. There were a few sports that were considered kind of alternative that you could do and not lose social status among the more progressive students: the cross-country team and the swim team.

My gym teacher in 10th grade was Ken Bergstedt. One day he taught Physical Education, the next day, Health. These were the only classes segregated by gender. In Health class he loved to tell stories about the Korean War. Once, I raised my hand and said “Mr. Bergstedt, I don’t understand the connection between the Korean War and endocrine system.” Half the class laughed; the other half wondered what the endocrine system was. I was letting him know that I wasn’t OK with him using my education time to share war stories.

He had another practice that was even more reprehensible: a punishment system he called “swats.” He had a short canoe paddle. If he didn’t like what somebody had done in class, he would say, “OK Robert, that’s going to be three swats at the end of class.” We would go down to the locker room and then he would hand somebody the canoe paddle and say, “Alright give Robert his three swats.” Robert had to bend over, grab his ankles and some kid would swat Robert’s ass three times. If Mr. Bergstedt didn’t like the energy that you put into the swats, he would give Robert the paddle and have him give you three swats.

One day he made the mistake of giving me the paddle. I looked at the guy I was supposed to hit and smiled. He bent over, not knowing why I was smiling. I took the canoe paddle and swung it high over his butt, slamming it into the concrete wall of the locker room, shattering the canoe paddle. I gave Mr. Bergstedt the paddle and said, “Take it up with the School Board,” then went to my locker, changed clothes, and went to my next class.

Dance allowed me to be physical without feeling like I had to compromise my value system around participating in a kind of militarism. It was a chance to enjoy having a body; enjoy the somatic sensations without feeling like I had to win—a paradigm that I wasn’t interested in. Once I started taking classes I discovered I loved it.

Some dance class days, I would wear overalls so I could throw them on over my leotard and tights. Once, after class I came into the Evans scholars house and sat down in the living room. Another Evans scholar was reading the course catalog. He said “They offer dance at the University of Minnesota?! Imagine if somebody in this house signed up for a dance class.” I stood up, undid the latches to my overalls, dropped them to the floor, picked them up and walked out of the room.

Dance became a way for me to also start to make sense of the world. It was how I wanted to move and breathe.

Dance, and Gay Life in Berlin

I graduated with a double major in Biology and German. My junior year I spent on an exchange program at the Free University in West Berlin. All my classes were in German. Berlin was really important to my whole coming out process. There I was, just one person in this big metropolitan city. Nobody had any expectations of who I was or how I should be. I was not immediately in gay clubs every night, but it gave me permission to allow myself to come out, to explore and begin to make sense of my sexuality and my desires. If you were looking for a place to escape from the Midwest and explore your identity, Berlin was probably one of the best places in the world.

When it comes to culture, Berlin is to Germany like New York is to the United States. But the modern dance world in Berlin had not recovered from World War Two. There was ballet, tap, and jazz at the University but no modern dance. I said to the FU Sport Director, “Given Germany’s role in the development of modern dance in the world, I’m surprised you don’t offer it.“ He said they’d be willing to offer if I could suggest somebody to teach it. I found one woman who had been a student of Mary Wigman, but she was too busy. The director said, “You seem to know a lot about all this. Why don’t you teach a class?”

I knew that was equivalent to asking someone with four quarters of college Spanish to teach the language — but I didn’t say no. I said I needed to think about it.

Then, during my next class, the universe directed me to sit next to an American woman from LA with a dance background. I told her about the teaching offer and said, “Why don’t we teach a class together?” So that is how Sunny Burke and I ended up teaching modern dance classes at the Free University of Berlin.

Teaching helped me realize how little I knew and made me hungrier for modern dance classes when I came back to Minneapolis.

Discovering and Introducing Contact Improvisation to Minneapolis

I finished college in 1976 with no student debt and decided instead of pursuing a full-time job, I would keep dancing and see what happened. I took classes at Nancy Hauser’s Dance school at the Guild of Performing Arts on Cedar Ave.

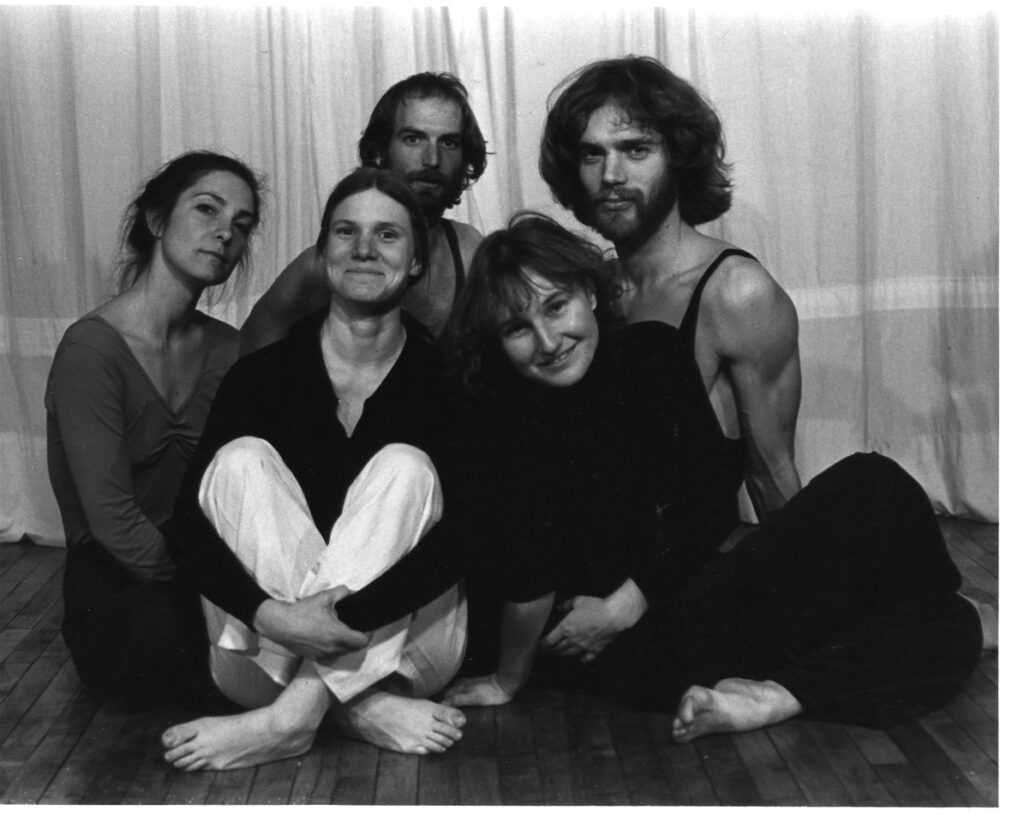

In January of 1976, Mary Cerny, a member of Nancy’s Company, came back from a sabbatical in San Francisco and taught the first contact improvisation class in Minneapolis. I took it and loved it. When Mary left Nancy’s company that summer to move to England, a group of us who’d been taking her classes, decided to get together a couple times a week to keep contact improvisation going in the Cities. In the fall of 1976, we formed what would eventually become known as Contactworks. That launched me into the performing arts world.

To survive, I lived in a collective house in South Minneapolis. Three men and three women divided up the $300 monthly rent. We shared our meals. One night a week you were responsible for cooking, and one day a week you were on your own. Men paid $16 a week for groceries and women paid $12. A part time job as a school bus driver covered those basic living expenses. By the end of a year, I was able to leave the school bus job and cobble together a living as a dance teacher.

I stayed with Contactworks through 1980. We were all young adults exploring questions that mattered to us. I was the only man in the group. I asked “What can we do to undermine the willingness of the audience to perceive me dancing with you, a woman, rolling over each other, in a heterosexual context? I don’t think a lot of audience members seeing you dancing with each other presume that this is a lesbian relationship. How, as artists can we undermine those assumptions?” We would scratch our heads, talk about it, read things. We grappled with questions we really cared about. We explored nude contact – a different level of intimacy as human bodies. It was a great laboratory. If any of us had an idea for a choreographed piece, we could use Contactworks as a place to create new dance vocabulary.

We had a studio in a building that no longer exists, near where the Star Tribune headquarters was in the old days, downtown, west of city hall. Sometimes we performed in that studio. One of my jobs in the collective was to find outside gigs, to contact colleges and find other places for us to perform. We performed quite a lot, in both mainstream and alternative venues.

Action Theater and Incorporating Gay Men’s Issues into Dance

What was missing for me during those years with Contactworks was a growing sense that I needed to integrate my personal politics as a gay man into my artistic voice. By the summer of 1980 I realized I had to leave Contactworks, not because they hadn’t been supportive of me, but because I needed to be around other gay men.

Contactworks had brought Ruth Zaporah to Minneapolis as a guest artist, who performed what she called “Action Theater” combining dance, language, and sound to create a kind of improvised theater. I liked the idea of adding language.

Susan Delattre, Erika Thorne, who had also studied with Ruth, and I, began to meet on a regular basis to improvise. Erika is an out lesbian. She and I did some performing together in a program that we called “Nobody Gets Pregnant,” undermining the expectation that our male/female duet would be romantic.

Building a Dance Loft on Hennepin and 7th St.

I came across this space in downtown Minneapolis; an empty third floor in a three-story building next to Shinders, on the corner of 7th and Hennepin. I talked to the owner, Peter, who was of Greek descent and ran the Best Steakhouse next to Shinders. Fortunately for me, during my time in Berlin I had taken a six-week vacation in Greece and learned some Greek. Peter loved the fact that this American kid spoke some Greek. We sat down at Moby Dicks and signed a lease for the whole third floor of his building; 3200 square feet of space for $300 a month including heat. It was really raw — abandoned — space. I needed to install a dance floor.

At that time the city, in its infinite lack of wisdom, had decided to close Nicollet Ave and put up a Kmart. There was a three-story building on Lake Street that was going to be torn down. I found out that the third floor of that building used to be a ballroom with a beautiful hardwood floor. I called 8th ward Council person Mark Kaplan to find out if I could remove the flooring before the building got demolished. The secretary for Kaplan had gone to dances in that ballroom and she loved the idea that somebody would save the floor from the ballroom of her teenage years. She got me keys to the building. By that time, they had already torn down the building next door and filled in the lot with sand. I got a crew of volunteers together. We found that if we dropped the floorboards out the window like spears and they stabbed into the sand, then we could bundle them up, and put them in the back of a van, and drive them downtown, where we built a pulley system to hoist them up the back fire escape of my new space. We had to pull the old nails out. It was a huge undertaking.

I lived and worked in that space. I wanted to have a bathtub but the only drain that I could get the bathtub to drain through was a sink drain. I built a platform to elevate the bathtub three feet so that it could drain downward through the former sink drain.

Having this space was important. It meant that I could teach a class or do a performance whenever I wanted, without getting somebody’s approval to include my work in their program. It was a hugely inspiring for my creativity. I would rent the space out to other people to rehearse, and that helped to pay my rent. Dancers appreciated the oil-finished floor that allows you to grip when you want to grip and slide when you want to slide.

I didn’t have a car most of that time. Hennepin Avenue between 6th and 7th streets was sort of the last little bit of honky-tonk downtown Minneapolis, corner to corner with no alleys, no parking lots, just building next to building filled with bookstores, bars, music stores, head shops, video arcades, an old hotel, people coming and going, buying stuff all day long. Across the street they had just put up the City Center, but small businesses, like the Nankin Café were still thriving.

People would talk about all the crime on the block; the bad element hanging out on block E or whatever, but my experience was that if there was indeed crime on the block, it was probably because there was a conscious choice to not respond to situations as quickly as one might respond in neighborhoods with resources, so that the city could point to the segment of downtown as a place that’s problematic and in need of renewal. I had an experience that helped solidify that in my mind. It was Tuesday morning maybe 10:00 o’clock. The entrance to my loft was in the middle of the building on street level. That door was always locked from the inside. So I heard what sounded like somebody trying to break the door down. I was alone in the building, up on the third floor. I called 911. It took 45 minutes to get a squad car to respond to an active break-in call. (The downtown precinct was so close to my place; you could walk backwards with a donut and a cup of coffee and get there faster). That’s just anecdotal, but it points to the possibility that the city wanted the block to be considered blighted, so that they could offer it to some developer to redevelop.

Hennepin Ave between 6th and 7th streets, was the gay-central corridor of Minneapolis in 1980: I was two blocks from the Saloon, and two blocks from Gay 90s. In those days gay bars were very much the center of gay men’s culture. If I wanted to go out but didn’t want to stay out, I could take a walk, be out dancing for 20 minutes, and be home in 1/2 an hour.

Making Art Space for Myself and Others in Downtown Minneapolis

My space was used by all kinds of people. I had a children’s show that I was doing through Young Audiences, in collaboration with WAMSO, the Women’s Association of the Minnesota Symphony Orchestra. I hosted their Halloween fundraiser for Young Audiences. They were a fabulous group of women, and from a very different social segment than those who lived, worked and frequented Hennepin Ave. It was a night in late October. I arranged for somebody from the farmers market to deliver like three dozen pumpkins. The audience came up the stairs from the street up to the space. Pumpkins lining the whole way, that made the occasion magical.

Another time, the Walker Art Center hosted a reception there. Nigel Redden was the director of performing arts at the Walker at that time and he knew me through Contactworks. At some point in the evening, somebody broke the plumbing in the bathroom so that the bathroom sink was spraying, in a very beautiful way, creating a fountain, that, fortunately, landed in the bathtub. It was as if somebody had designed it.

One of the best projects that I got to do while I was living on Block E, was a collaboration with filmmaker Dan Polsfuss and poet Roy McBride we called Shinders to Shinders, a fifteen-minute, sixteen-millimeter film that portrays life on my block of Hennepin Ave during the time that I lived there.

We showed the film on the Avenue, projecting it onto a billboard above Shinders on 7th. It stopped traffic as drivers slowed to watch the movie. It was a magical time.

By 1983, the city had discovered we lived in the building. By then I had friends who had taken over the second floor. It was not in the interests of the eventual developers to have artists living in the building. They wanted to demolish the whole block. Artists might organize resistance to the block being torn down. They came down on us, saying the block wasn’t zoned for residents.

Forced out of my fabulous loft space in downtown Minneapolis, I moved to Washington, D.C. in June of 1983.

An Education in Creating Art and Community in Washington, D.C.

I wanted to go to New York, but I didn’t have a place to land there. I had a friend who lived in D.C. and had a two-bedroom apartment where I could live in the Adams-Morgan neighborhood. The week I got to D.C., gay pride had just happened. I found a program for the week, listing all the different stuff that had happened. There was a performance artist/poet named Chasen Gaver whose name was listed in the program, who I took a chance and called. With cold-calling like that, I managed to build a biracial network of gay men and lesbians – Black and white. (I don’t recall any Native, Latino, or Asian people in the network).

Being brand new to town, it seemed easier for me to bring these people together. We taught each other. I was introduced to the feminist Kitchen Table Press, became acquainted with the writings of people like Audre Lorde, learned about Langston Hughes and met some of his peers from the Harlem Renaissance who were still living in D.C. at the time. All of this helped me to find my own voice as a white gay man who had something to say, who didn’t want to be made invisible by the world. I also met people in the dance community: Liz Lerman had a company at that time: Dancers of the Third Age. Greg Reynolds had moved back to DC after having danced with Paul Taylor in New York. Nigel Redden had left the Walker in Minneapolis and moved to Washington to run the dance program for the National Endowment for the Arts. I moved into Nigel’s house on Capitol Hill and helped him renovate in exchange for rent.

I was there in D.C., meeting people in the gay community and the dance community, and still living a very kind of bohemian existence, enjoying the change from Minneapolis. Liz Lerman let me use her studio to do a concert in October of 1983. On my 30th birthday I got a very favorable review in the Washington Post about my dance concert. If you want to be appreciated back home, it helps to go make it somewhere else. Then the people back home start to take you more seriously.

I had the opportunity to dance with Pola Nireńska, in a concert funded by the national Endowment for the Arts. Pola had been in Mary Wigman’s company in Germany. Being Jewish and Polish, she fled Nazi Germany for the United States. She was married to Jan Karski, the Polish anti-fascist. I had no idea who Jan Karski was. I learned, when he died and there was a half-page obituary in the New Times, that he had been instrumental in getting word to the West about the horrors of the Nazis in Poland.

My time in Washington was rich in many directions. I met Andrew Hudson, a painter who taught at the Corcoran School. He would hire me to model for him. I would do a couple of hours of modeling, and then he’d make a lovely lunch for us. He paid me well. I think it was his way of helping another gay man and another artist.

Working With Out Gay Dancer and Writer Remy Charlip in New York

While I was in D.C., I found out that Remy Charlip was going to be teaching a series of dance classes specifically for men in New York City. Bill Herron, a dancer in Minneapolis, had told me I would love the work of Remy Charlip. Based on this recommendation I decided to sign up for his workshops. I could drive up from DC for four weekends.

Remy was my parents’ age, but unlike, for example, Merce Cunningham, who was happy to stay in the closet, Remy was having none of that. He was out to the world. His unwavering support allowed me to minimize my own imposter’s syndrome. His confidence in me helped me find confidence in myself.

I think we all suffer from some amount of self-doubt. For me, coming up in the art world, starting as late as I did, and not through the normal channels, like years of ballet or even standard modern dance, being on the fringe with my focus on contact improvisation, all of that made it easy for me to have doubts about my abilities. Remy allowed me to get beyond my fears and accept myself as an artist. The last workshop weekend he was explaining that his next big project was a show he called Ten Men. I thought to myself, how great would it be to be one of those ten men. I found the courage to tell Remy that. He got back to me in a couple weeks and said “I’d love to have you be one of the ten dancers.”

So I made plans to move from Washington and build a new life for myself in New York City.

That summer, in between my move from D.C. to New York, I returned to Minneapolis to work at the Children’s Theater. The whole school had just fallen apart with the John Clark Donahue scandal and they wanted somebody to teach in their summer program who had no previous affiliation with the Children’s Theater. I taught in the summer program, and then got in my little Nissan Sentra and drove back to my apartment in Brooklyn.

New York was a very intense, brief chapter in my life. I supported myself, rehearsing with Remy and doing some arts administrative stuff for him. Remy’s rehearsals were such a peaceful loving and supportive environment to work in.

The other group I got involved with New York was called Men of All Colors Together, a gay men’s organization. They had a chapter in Washington and even one in Minneapolis, where it was called Black and White Men Together. New York was ahead of the curve, wanting it to be more than just Black and white. It was a great group. Every Friday night they would have a gathering for consciousness-raising sessions. They would have cultural outings. I remember this one guy—James Credle, who had been a medic during the Vietnam War—giving a talk to us about how the army would hire him to be with GIs as they were dying and bleeding in the field, but, had they known that he was gay they would have thrown him out of the service. The group was very mixed in terms of people’s backgrounds. It was a great opportunity for me to be in the mix with Latinos, Asians, Native Americans, African Americans, and whites, figuring out how we want to be with each other as gay men.

One day I was sitting in the subway and somebody across from me was reading the New York Times. The page facing me had a photograph of me! It was one of the promo photos for the Ten Men show. I thought, “Wow, I must really be a dancer. The New York Times has a picture of me as a dancer, in their Arts and Entertainment section.” It was such a pivotal time for me in terms of just the joy of doing the work with Remy making the connections with him.

At the same time this was 1984. New York was about to become the heart of the AIDS epidemic, like a tsunami out in the ocean: already in the city, but about to crash with a lot more force and violence. I think New York is always hard. It’s expensive, loud, and crowded. Once the concert with Remy was over, I got contacted by Karon Sherarts from Film In the Cities. She had a gig for me working with a group of junior high school breakdancers. I ended up coming back to Minnesota, to Duluth. I stayed in my brother’s log cabin on Lake Superior. He had electricity but no running water, and a wood burning stove. I stoked the fire and then went to Washington Junior High to work with the break dancing kids.

The First Patrick’s Cabaret

Back in Minneapolis, I needed a place to dance. I approached Sister Pat who was the principal at Saint Stephens School, down the hill from the Art Institute—a very progressive kind of inner-city, Catholic school—and I offered her a barter. I would teach a creative movement class to her K-6 classes, and in exchange she would give me permission to use the school gym whenever it wasn’t being used by somebody else. The school didn’t really have any money to pay a dance teacher, but they had space and that space had value for me. Now I had a place to rehearse and to invite other artists to come and work with me.

That led, in 1986, to the first Patrick’s Cabaret, in the gym at Saint Stephen School on a Friday night. I had the idea that I would do something similar to Walker’s choreographers’ evenings but it would not be all dance; it would be any anything that could be on stage; dance, poetry, theater, etc. I’d just look through my rolodex and called people and said, “Do you have 5 to 15 minutes of anything that you’re working on that you’d like to show people?” Once enough people said yes, I stopped calling, and put together a flyer.

I did Patrick’s Cabaret at the school for three years. In 1989 I moved into a storefront space just across the freeway, in the Phillips neighborhood. We didn’t have as much space as we had St. Stephens, but the advantage was we could do a show Friday night and then repeat the same show Saturday night. I had the intuition that there would be enough demand for that.

Creating Dances that Addressed the AIDS Pandemic

The AIDS epidemic was hitting hard in Minneapolis at that time. Sometimes I would get a call about a memorial service for somebody, and I didn’t even know they were sick. From 1989 through 1996 or ’97 when there were finally effective combinations of medicines to treat HIV, it was a really hard time, like living in a war zone. It was not the sole focus, but it definitely influenced my work. There were two pieces in particular, that I developed, to address how it was impacting my life.

Too Soon Lost, was a ten-minute mixed-media piece. I had made a time-lapse film of the demolition of my old neighborhood on Hennepin from 6th to 7th Street. I played the film and told a story about the first building on the block and then I would segue to friend who had died in the AIDS epidemic, telling a short story of his life, then go to the next building, and then talk about another friend: seven buildings, six friends. In the background I played Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings, the saddest piece of music that I knew. After each building story, I put up a realtors Open House sign. When finished talking about a friend, I would drop a flower at the foot of the sign, making it a tombstone. I played the demolition film in reverse, from rubble and debris, ending with the block intact again. That helped somehow, to not leave the audience in total despair.

The other piece that I performed at that time, I called Queer Thinking. It had three parts, all based on autobiographical stories from my life. In the first part I came on stage in the persona of Tanya, a drag queen based on Patricia Hearst during her days with the Symbionese Liberation Army: high heels, fishnets, a micro miniskirt, an audacious wide red cape with enormous shoulder pads. I had long blonde hair at the time. I wore it in a ponytail tied on top of my head so all of this blonde hair cascaded down the sides of my head. The focus of Tanya’s story was how homophobia impacted my life. In the second section, I’m completely naked. I talk about ways in which I internalized homophobia, becoming my own enemy. The third segment of the show, I come on stage dressed up like an Act Up activist and talked about strategies for dealing with homophobia when it arises. It started out as a 30 minute piece, and over time it evolved and I continued to add stories. In its final evolution, it was an hour long.

Those two pieces were among the most important works I’ve created as an artist, and I think they really capture a spirit of the time. I got to perform them a lot and I got very favorable reactions. I did them both in a show in New York in September of 1992, and got a great review in the New York Times. I took the pieces around the United States and Canada, and to Berlin, Potsdam, Dublin, and Belfast.

Running Patrick’s Cabaret

With Patrick’s Cabaret, I had a venue that I could perform in whenever I wanted, which was a huge asset. I didn’t have to wait for opportunities to perform, based on approval of some individual, institution or committee. As the master of ceremonies, I had a spontaneous monologue I would create each night for 3 to 15 minutes depending upon how involved it got. The fact that my own career was meeting with success locally, regionally, nationally and even internationally, meant that Patrick’s Cabaret became a more important venue locally. It had more prestige and power because a successful artist was its director.

So often power comes with negative connotations. I became conscious of how important it was to create a situation that empowered artists. I never auditioned anybody to perform in Patrick’s Cabaret. There was one requirement: you had to come and see a show before you could be in one. I did that partly for myself. I didn’t want to have somebody come in with expectations I could not provide. Without auditions, artists didn’t have to think, “What would Patrick like?” They could think, “What do I want to do?” Artists create their most interesting stuff when they are following their own muse. I also did it to make my life simpler as an administrator. I just kept a calendar. It might be six or even twelve months before somebody would get on the calendar, but anybody who wanted to, could do it. I think it had a transformative impact on the local performing arts community, to democratize the means of artistic production.

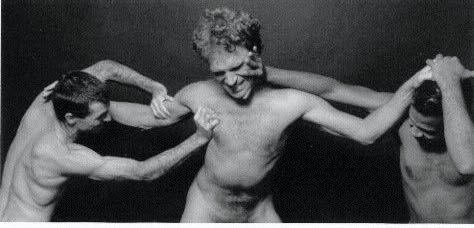

A Gay Men’s Dance Trio: Unsafe/Unsuited

In the mid 90s, I initiated a trio of three dancer/performance artists: Ishmael Houston Jones from New York, Keith Hennessy from San Francisco, and myself. All three of us had a background in contact improvisation and performance art and all three of us had a reputation for sometimes being naked on stage. I was motivated to start this trio because I wanted to bring a clear and more distinct queer voice into the world of contact improvisation. Many of the men in dance are gay, but in the world of contact improvisation that was less the case. It was one of the straighter corners of the dance world. Keith, Ishmael and I traveled to San Francisco and worked together a while, then to New York, and then Minneapolis where we premiered a series sponsored by the Walker, at the Southern Theater. We called the show Unsafe/Unsuited. We also performed in Oakland, New York, Houston, San Antonio and Washington DC. Even Torino, Italy! It was pretty amazing, at the peak of the AIDS epidemic, three gay men performing, improvising, addressing our lives. When we did this show in New York Deborah Jowitt, a knowledgeable, intelligent dance critic from the Village Voice, brought her insight to it. She articulated things about the work that I intuitively sensed but had never talked about out loud and so that was it was a real gift to me.

The flip side of that story was that in Minneapolis, Mike Steele, the main dance and theater critic didn’t come to our show. He could write more comfortably about gay men from other cities, but for him to write about a hometown boy who was gay made him uncomfortable. I took solace when the review came out in the Village Voice. I mailed him a copy and said “Here is what you missed.”

Too Radical for the Minnesota AIDS Project

I remember talking with another radical gay man about being on the board of directors of the Minnesota AIDS Project. He said: You would never get elected. They are way too mainstream for you.” I guess I kind of knew that, but to have somebody clearly articulate it was a reality check. It gave me a certain freedom.

The Minnesota AIDS Project was on Nicollet Ave just off Franklin for a while. For a long time they had no sign on the outside of the building. I would publicly criticize them for that, saying, “Your internalized AIDS-phobia leads you to think that it’s a smart choice. You’re thinking that there are people who would be afraid of coming in a building that says AIDS on the outside for fear that it would out them to the world, and they want to keep their HIV or AIDS status private. But what you don’t realize is, in making that choice, there are activists like me who will not come in your building because we are so angry at your willingness to buy into the closet as opposed to inspiring people to come out and insist that the world adapt. Being out living with HIV, is like being out as a gay man. The problem isn’t us. The problem is the attitude of the world.

Finding a New Home for Patrick’s Cabaret

In 1996, the city discovered that Patrick’s Cabaret didn’t have a theater license. They closed us down and we had to jump through a lot of hoops to get it reopened, including going to zoning meetings.

Most of the other commercial activity in our Phillips neighborhood was illicit: drug dealing and prostitution. At the zoning meeting, city employees had a map showing the neighborhood. I said “Look at this map. You know the building immediately behind our building? That’s not there anymore, because it burned down. When it was here, it was the most active crack house in the neighborhood. If we move up the block, this building here, is now the active crack house in the neighborhood, and this building next door, it’s boarded up. The owner is in jail for drug dealing. You talk about the Cabaret being detrimental to “a stable residential neighborhood” I wonder what zip code you live in?

The city decided that we could stay there if we were willing to become a “lodge” which had easier zoning regulation then a theater. As a lodge, we could put on events for our members and for their guests. We could live with that for a while, but we still had fire code restrictions because of changes that needed to be made in the space. So only 50 people at a time could come to a show, when at that time, we were usually averaging about 80 people per show.

We ended up finding a different building. We decided to buy and renovate the old fire station on Minnehaha and Lake St. That purchase was made possible by a woman who prefers to be called the fairy godmother. She loved what we were doing with Patrick’s Cabaret; she was a woman of means and she wanted her kids to learn how to give their money away.

She bought the Firehouse and asked me what kind of rental agreement I wanted. I said 20 years at a dollar a month, thinking that I was being as outlandish as a person could possibly be. Her response was, “I’ll have my lawyers draw it up.” It was like winning the lottery without having bought a ticket.

That was 1999. We were able to build a wonderful floor for the dancers in town to have a world-class surface. I left it in 2001 and came back a few years later. I had had the intention of turning it over to the next generation. That didn’t work out. In 2005, I contacted the board and said I would be interested in coming back. They’d had a plan to merge two organizations. I thought that would not be good for either. So I came back to the Cabaret and did a lot to stabilize certain things that were needed if you’re going to survive as a small arts organization. I stayed through January of 2009.

At that point I felt like I needed to leave so I could focus on my own performing work. I had become an arts administrator not because I had always dreamt of being an arts administrator. I left. The organization kept going until it closed in June of 2018.

A conflict came up between some of the staff, some of the board members and the fairy godmother. They were considering leaving the Firehouse, being nomadic. I foresaw a disaster in the making. I did my best to share my concerns. A big part was financial. Leave the Firehouse and your budget shrinks. With a shrunken budget comes a reduction in general operating support from the state arts board that gives general support that is based on a percentage of your budget. I was told they were not interested in my advice. I felt like there was ageism involved in that decision. I wasn’t in a position where I could insist that they do anything because I wasn’t on the board, even though I had been the founder. Sadly, my prediction came true: in 2018, Patrick’s Cabaret ceased to exist as a nonprofit organization.

The good news was people knew of the experience of Patrick’s Cabaret and could take the idea and adapt it for their own use. I’ve seen that happen in numerous situations and been glad for it. At the same time, I was sad we lost a performing space in town. Sometimes I thought, oh maybe this is what it’s like to be a parent. At some point you have to let go and let the kids do whatever it is they’re going to do, enjoying their successes and suffer the consequences of their failures.

A Water Ballet With Boats As Dancers

It did free me up to put a lot of energy into two very big projects. In 2010 I got to create a dance on the Havel River in Potsdam near Berlin. The dancers were the boats and the stage was the river. There were kayaks, canoes, sailboats and vintage yachts, 50 different boats. It was an hour long, meditative piece for the audience to enjoy watching from the shore. I was able to do a version of it here on the Mississippi River in 2015. The rivers are so different. The river in Potsdam is so slow moving that is more like being on a lake. The Mississippi River has a current, but the currents not always the same, so one week of rehearsal it might be strong and other days it might be barely noticeable. They were huge community-based events in both cases.

Leaves of Grass: Retrospective on Walt Whitman

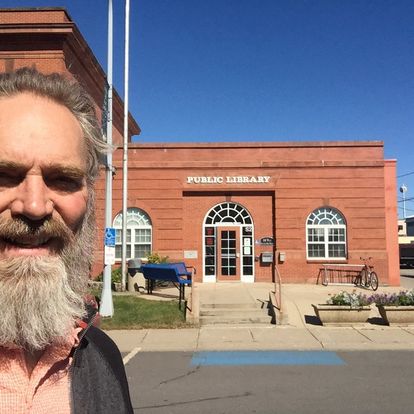

My other project, which I’ve been working on for a decade, is my show Leaves of Grass, about Walt Whitman. It has given me a chance to work on a project that is not autobiographical, but continues to work with themes that I’ve worked with my whole life as a performer: bringing material about men loving men onto the stage.

When I first came out as a young gay man everybody was saying the most important thing you can do as a gay person is to come out. So it is interesting to tell the story of a man who much of the world did not know was gay. Whitman’s fame has opened doors for this material that are not open for Patrick Scully, radical queer performance artist, like the chance to perform at the library in Two Harbors, Minnesota.

I did a lot of research for Leaves of Grass. I have a bibliography of more than 50 books. Then I needed to write the script. I’m sure, as a writer, you’ve dealt with this: they want 500 words and you’ve got 50 pages.

In some ways I got to recreate the work environment I had experienced with Remy, bringing together men of different ages, many of them gay men. In order for Walt Whitman to survive, he code switched. I used that as a theme in the dance section. When you watch two men dance: you might think, are they lovers, friends, brothers, neighbors, coworkers? What lens do you choose to look at these dancers?

I created a really big version of the show that we did at Illusion theater with two actors and 18 dancers. I hired Nancy Mason Hauser to videotape our rehearsals and performances so that at some point I could go back into all that videotape and have it edited down and then tour as a one man show but bring the dancers along as video projections, and sometimes a low tech version, with just me, no video. I have been able to do that with some support from the state arts board, traveling to approximately half of the 87 counties in Minnesota with the show.

I’ve also done it at the Guthrie in a totally sold-out run.

I first went to the Guthrie as a sophomore in high school with my German class, to see Bertolt Brecht’s the Resistible Rise of Arturo UI. To be able to go to the Guthrie with the show that I had created, written, and performed was really a peak experience for me.

Since the pandemic, Leaves of Grass has been on hold, as I work on other things. A couple of years ago Mark Wojahn, a local filmmaker, said he wanted to make a documentary about me. It’s called The Dance is Not Over. He came with me when I toured Leaves of Grass, interviewed me, my partner Kevin, and other people in the community. His editor said he wanted to take the Guthrie footage, and make it into another movie, so that is done and actually premiered a couple months ago at the Minneapolis/ Saint Paul Film Festival. Mark is still working on the bigger film about my life.

Patrick’s Cabaret Reprise in the Era of COVID

When COVID hit, I realized there was this huge need for artists and audiences to stay connected to each other. By then Patrick’s Cabaret had been closed for more than a year. I decided to revive the name and start doing Patrick’s Cabaret online, as a way to keep myself and other artists connected with audiences. I’ve done probably a dozen of them, ten online and two of outdoors last summer on Nicollet Island where I live.

I’m 68 now. That’s no longer middle aged. I can just say old. I learned from the feminists in the 70s how to change language and embrace terms considered negative, turning them into a positive. I wrote a new show that’s called The Third Act, which looks at the challenges of aging in such an ageist culture. I performed that back in February, online, with the support of Illusion Theater. I’m figuring out where to go next with that show. It is a one-person show, designed specifically to be able to have a conversation with the audience, most of whom I expect will be older people, coming to share their experiences.

The 2020 Minneapolis Uprising

Following the night that Lake Street burned, I went down to the firehouse at 5:00 AM. I didn’t know if the place that had been the home of Patrick’s Cabaret would still be there. The National Guard were standing in the street. Lots of buildings in the neighborhood were still actively on fire. The firehouse had been damaged, but it was still there, which felt kind of like a miracle to me. I took a 360-degree circle with my video camera, capturing that moment in time. I hope we will look back on it and recognize it as a pivotal moment. I hope people are not too anxious to run back to business as usual.

At this moment, during the corona pandemic, the only thing that seems for sure is that the new normal is the absence of the new normal.

My point of view is that if there’s something watershed that happened here in 2020 it is that enough people started paying attention. It raises the possibility of enough political momentum that some real change can be manifested. Audre Lord talks about how there is no hierarchy of oppression. My hope is that the consciousness that she articulated will motivate people to engage in making change happen, relative to issues of race, gender, sexual orientation, class, and age. We need racial equity and we need to approach that work intersectionally.

Creating Free Spaces: A Life Project

The personal is political indeed. Particularly for people in the queer community. You know it was Oscar Wilde’s lover, Alfred Douglas, who coined the phrase, “the love that dare not speak its name.” That speaks volumes about who we are and how our oppression is manifested.

I have taken it on, as my vision on the planet, to do what I can to create space for me to live as freely and openly and honestly as I can, and to create space for other people to do the same. If I’m only creating the space for me, I don’t get to draw on as many new resources, whether it’s a psychic space or a physical space. I realize that if I’m willing to share space, more space gets created.