I don’t feel I have been traumatized by my upbringing. I became very resilient at a young age. I will say, however, I can only look at the Cass County Social Services and the foster care system with disdain. The word that comes to mind is “objectified.” The County’s social services treated Native American children as objects, akin to being a lamp or other household object, to be placed here or there at their whim.

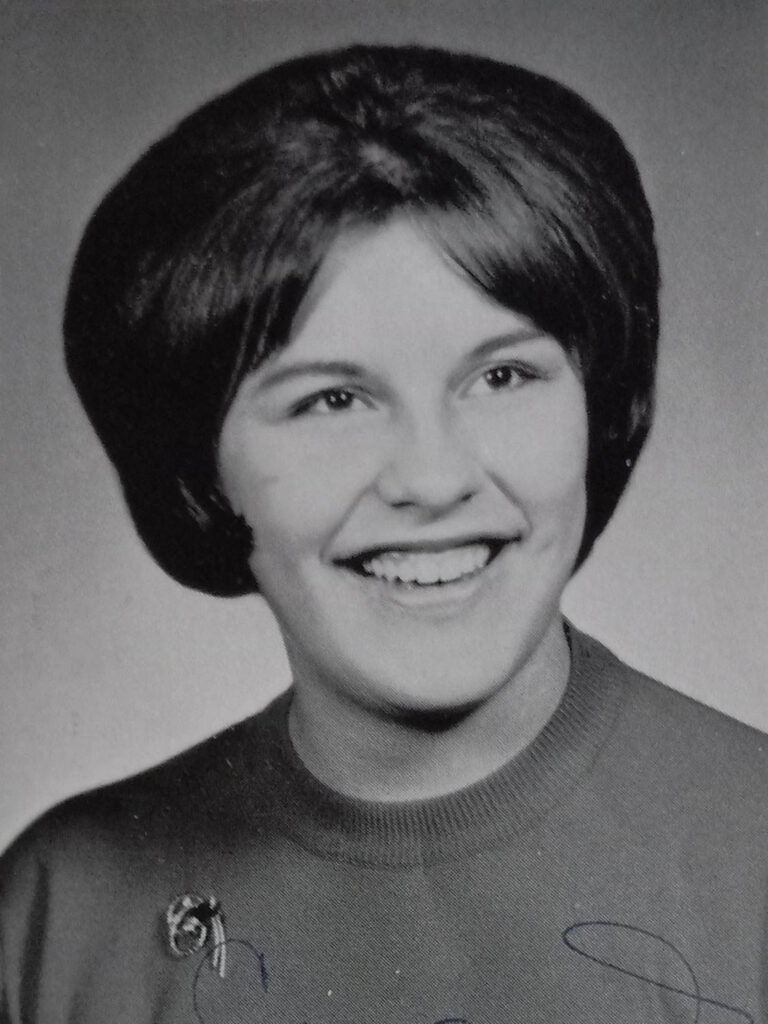

— Connie Edberg

Born on the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe Reservation

I did not speak English until I was five years old. I spoke the language of my grandmother, a traditional Ojibwe speaker. Now, when I hear Ojibwe, I understand it, but I don’t speak it fluently. Someday I would like to see a hypnotist to see if it might take me back to that time when I had the language. Sometimes, when I am in a quiet setting, or quiet repose, a word will come to me. Recently mashtadim came to mind. My grandsons love horses, as I do. I remembered the Ojibwe word for horses.

Growing Up in Foster Care

In the late 70s, I contacted Cass County Social Services to request my foster care records. The narrative was written by one social worker. Perhaps I had the same social worker the whole time. I do know I would get a visit occasionally. There was no heart in those visits. They would ask rote questions like “How far can you count?” and “Do you know your ABC’s?” I was young. I had no knowledge of the inner workings of the social services system.

I entered the foster system when my mother was admitted to the Ah-Gwah-Ching sanatorium with tuberculosis. In a recent conversation with a band member from Grand Portage, he revealed that that same thing happened with his mother. Talking with him I began to wonder if the tuberculosis diagnosis was another ruse the County’s social services used to separate Native American children from families and further fragment community ties.

I did have family, my mother’s sister, in Redby, a small community on the Red Lake Reservation. My aunt requested that I live with them, but Cass County didn’t consider it a viable placement. The goal of Cass County Social Service was placement with non-Native families off the reservation. When my mother recovered from tuberculosis and was released from the sanitarium, I did not return to the Leech Lake Ojibwe Reservation. From age five to eighteen I was placed in four white foster homes; three before aged nine. From nine until I graduated from high school, I lived with a fourth family.

A Childhood in the Woods, Waters, and Farms of Cass County, Minnesota

The first family I lived with owned a farm about 15 miles west of Backus. Farm-living was a fun time. They had a small operation that included baling hay. I especially liked the fall harvesting. Grain flying through threshing machines mesmerized me and the smell of fresh baled hay was intoxicating.

The family had two teenage daughters, about fourteen and fifteen years old. There were also two young boys in their care who helped to work on the farm. They were the “farmhands” who milked cows, fed livestock and poultry, help plowed fields, and planted seed. I lived there for a year and a half. They were licensed for two children and preferred to keep two boys who worked for him rather than me.

I was placed in another home in December 1953 in the middle of second grade: new family, new town. The social worker’s report at that time said She is a tomboy, a quick learner. Kindness and praise go far with her. She has adjusted to this home where she is receiving more attention.

In third grade, I had a teacher I loved. After school I stayed to wipe the blackboards, organize crayons, and clean the erasers. I was the teacher’s pet. My teacher was very lavish with praise. She wrote: Connie is third highest in her class, well behaved, well dressed, no behavior problems. She is gifted with obviously superior intelligence.

In that time, I learned how to ride a bike, roller skate, swim, and explore the riverbanks. I went to the movies once a week. On Sunday afternoon rides to visit their extended family, I learned about the surrounding lakes. It was a major vacation area called the Whitefish Chain of Lakes, an area known for its many resorts. They had one child at the time of my placement. A second child was born with serious health problems and needed additional care. Because of this family health crisis, I was again placed in another home.

Growing up in Cass County, I most often lived close to water, so I learned early how to swim and aquaplane in the summer, and ice skate in the winter. I liked being outside. Walking in the woods and on trails was a great adventure. I went alone. The other people were not interested in the great outdoors. To this day I remain an outdoor enthusiast.

I became a fearless horseback rider at age eleven. One special memory I have is of accepting the task of riding a Palomino Stallion to Walker, MN where it was going to lead the July fourth parade. We managed to ride together from Backus to the town of Hackensack before he stopped and would go no further. I had to call for a trailer to take him the rest of the way, to the parade route.

In the Twin Cities: Beauty School to Educator

After high school I moved to the Twin Cities. I spent the summer of ’64 caring for three children in the northern suburb of Spring Lake Park. That fall I enrolled in a beauty school near Lake Street and Nicollet Avenue. I lived with a friend from up north in a place off Grand Avenue. I was certified after eight months and began work at a salon owned & operated by Horst in the Towers, located behind where the Whole Foods Market is now at the intersection of Excelsior Boulevard and West Lake Street. I enrolled in Minneapolis Community College, and after a year, transferred to the University of Minnesota.

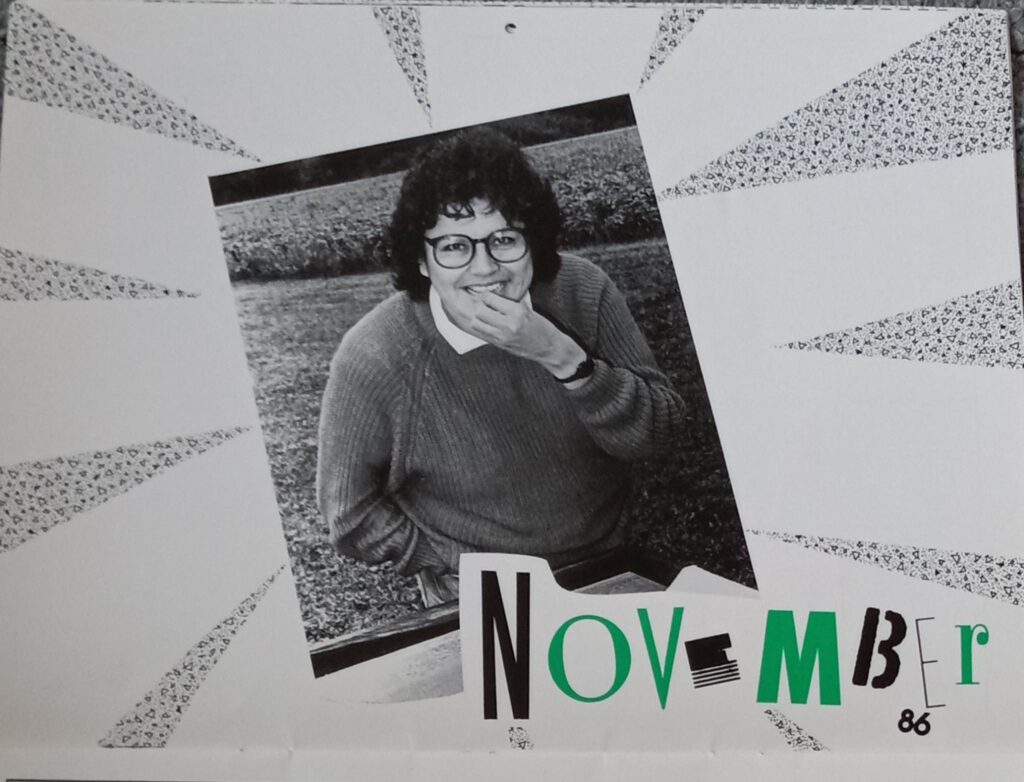

My degree is in American Studies with credits for a minor in American Indian Studies and an emphasis in African American Studies. After the University I went to Mankato State and completed coursework for a Library Sciences certification. I began my employment with Minneapolis Public Schools in the 1979-80 school year as a reading and writing specialist and a parent involvement specialist. My assignments took me to six different schools in the district, until 1983 when I took on a new role at the Office of Indian Education.

Office Of Indian Education, Minneapolis

The Director of Indian Education was fiercely committed to the community and led with an intimidating force. She was from Mole Lake Community. close to Lac du Flambeau in Wisconsin. Most were fearful of her abrupt manner. I never had that problem because I was strong willed. I believe she appreciated that.

The director was one of the founders of the National Indian Education Association, so she was called on to speak throughout Indian Country. We traveled together quite a bit: Oklahoma, D.C., Seattle, Salem, Oregon, Stevens Point, Madison, Chicago. She presented at conferences and conducted research. I liked going with her to the Library of Congress and the Newberry Library in Chicago. It was interesting, fun, and educational, to look through the microfiche and reference books. We wrote a curriculum on the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. I worked with artists on that project. People called it a “Conflict,” which made it sound like neighbors fighting over the back fence. It was a war.

My daughter, Shannon, just went to her first National Indian Education Conference. That was something I did for years.

Educator, Minneapolis Public Schools

I didn’t want to leave, but sadly we had a superintendent, Robert Ferrera who felt the OIE had too many teachers—that it was too top heavy with educators. He had us excessed and sent back into the schools. I went to Anderson for quite a while, then Four Winds on 24th and Chicago, back to Anderson, and then Bethune, a small K-5 school.

The district uses Media Specialists as prep teachers for music, art, homework, home economics, and industrial arts. And they use Media Specialists to relieve teachers for their one-hour prep time. I worked at many schools and did everything.

The Heartbreak of Losing Students

I cared very much for all the kids that I taught. Seven or eight of them have passed away; committed suicide or ODed. That’s crushing. I just lost a young man whose dad—a policeman who worked around Little Earth—was charged with sexual abuse of a girl and was sent to prison. The son was a really neat student, just bright and shiny. The community lost him last summer. About seven years ago he came up to me at a pow wow at the Indian Center and said “Are you Connie? I was in your Media class.” I said, “Oh my God!” He was such a little guy when I had him as a student. Now he was a grown adult man. I wish I could I have done something to save him.

You can hear the emotion in my voice. I see myself through these kids. Maybe it’s—what do you call that when you push grief issues down?—repressing feelings and memories. It’s just incredibly heartbreaking for me to think about these kids. I’m 77 years old and they are in their 30s. It makes me feel very sad. When I share these stories, other people will say “the damn drugs,” as if that explains everything. But I just can’t rectify. It’s in my heart but I can’t process it. It’s not processable.

Being a Grandma

My grandson, Avery, was born in 2002. I took the time off to take care of him. Aneila was born in 2005. I took care of her too. Sometimes I’d have both, sitting on my lap rocking. I also cared for Biiwan and Tyr when they were little. Tyr is seven now. I go meet his school bus once in a while.

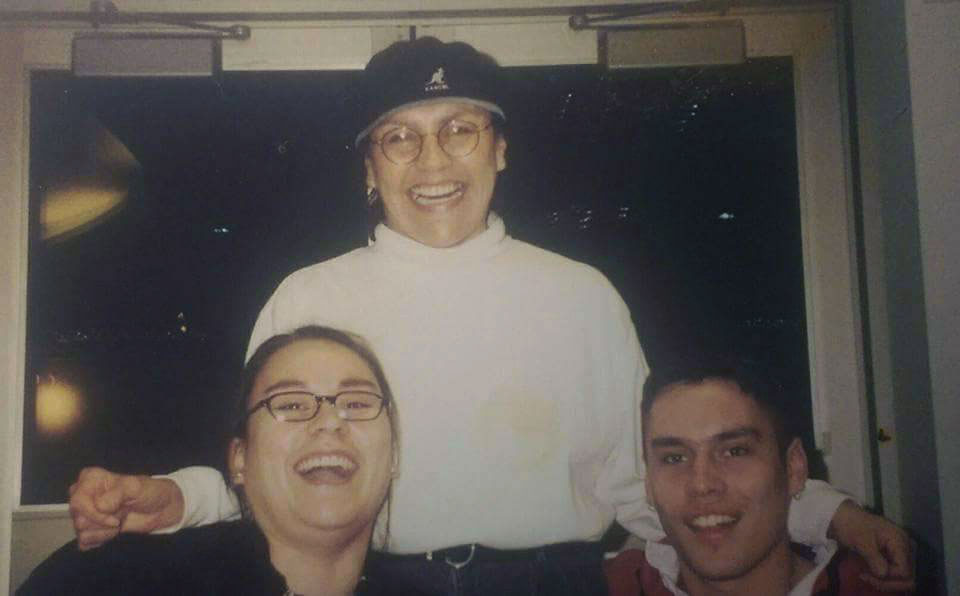

Reconnecting My Daughter With a Son I Put Up for Adoption

In addition to my son, Jeff, and my daughter, Shannon, I had a child when I was like 18 years old. His name is Joe Nordin. He lives out in California, down by San Diego. He came to visit us this past summer for four or five days, and Shannon got to meet him. His adoptive family had lived in Glenwood, MN, before they moved out to California. It was a real good visit.

I never felt a tinge of guilt for giving him up for adoption. I could not have been a mother at that age. He grew up with a wonderful family and has a good life.

Homelessness in My Phillips/Seward Neighborhood

I live across the street from the Taco Bell. There are homeless kids, homeless people that hang out there. They don’t have tents and sleeping bags—I mean it’s not counted as a homeless encampment, but they are there. A person used to come through with a stroller full of stuff. People would flock around her. I think she was dealing drugs. I’d walk over there and there’d be kids and I’d be worried about them wandering into the street. There is a fire station right there. Why isn’t the fire department doing something with these kids? Why aren’t they addressing the drug-dealing on their block? Recent evictions just make the problem of homelessness so much worse. We need to be going in the other direction.

Not Your “Authentic” Elder

I had the idea that becoming an elder meant that I would be required to live, know, and put into practice the traditional ways of the Ojibwe. Elders are supposed to transmit traditional knowledge, strengthen social cohesion, and help deliver positive attitudes such as reciprocity. But to me the whole idea of “elder” feels ingratiating and patronizing. It has been a personal struggle.

I was invited to an elementary school in south Minneapolis to share my perspective about being an elder with a class of fifth graders. The teacher was a former colleague at Four Winds where I taught Media from 1990 to 1995. Each student was given instructions and cues on how to interview me. A couple of them had questions ready to ask. The videographer created a video of this event, and it was online for a brief time. I asked politely to have it removed. It did not feel authentic to me.

Resilient, Despite an Objectifying System

I don’t feel I have been traumatized by my upbringing. I’ve not felt as if I was a victim of something. I became very resilient at a young age. I will say, however, I was bounced around in those early years and I can only look at the Cass County Social Services and the foster care system with disdain. The word that comes to mind is “objectified.” The County’s social services treated Native American children as objects. akin to being a lamp or other household object, to be placed here or there at their whim.

I began running right after Jeff was born and now he’s 45. Then I had an accident, and I couldn’t run anymore. I just have all this energy and I have to do something with it. If I can’t move, then I don’t feel good.

Like a lot of Native kids who were placed in foster homes, I grew up going to church, going to vacation Bible school, learning the songs. I do not feel strongly against Christianity, but I do not say I grew up in the church. I understand the church and its mysteries and have used the King James Version as a reference book. I have learned their holy songs. But Christianity ruined Native culture. For me, Native spirituality is a positive.