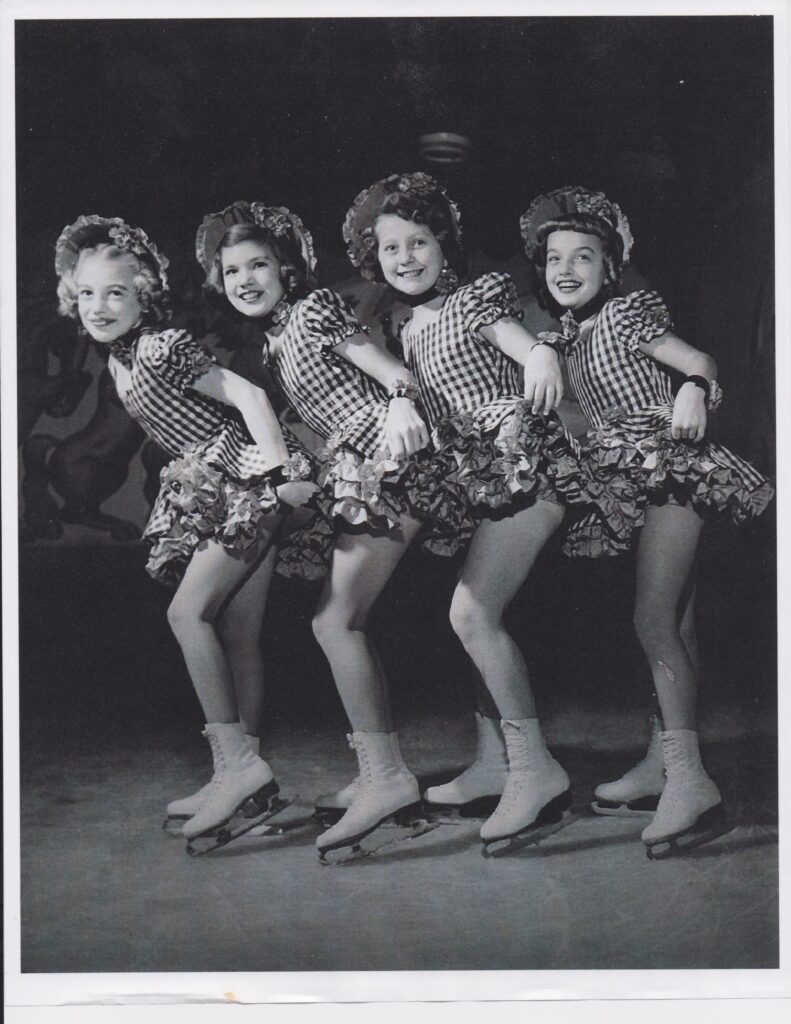

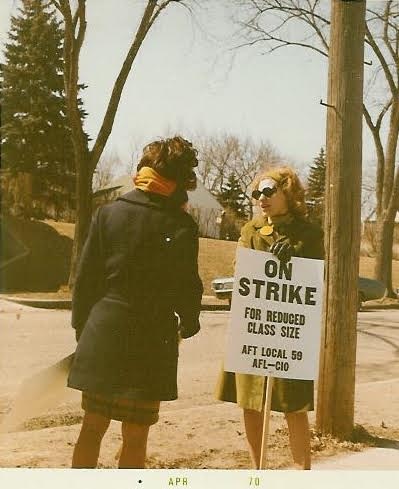

Going out on strike in 1970, I learned to speak up. I would walk the picket line in front of the driveway where the trucks came in. The Teamsters honored our picket lines. That felt really good. I kept a little make-up bag in the car in case I got arrested. We young teachers would go and picket at elementary schools after our shift at our own schools. I got into great shape from all the walking. We had our headquarters at 49th and Nicollet. Almost every afternoon we would have a rally at the Nicollet motel and occasional bigger rallies in front of the district office on 807 Broadway.

— Louise Sundin

Twin Cities Teachers’ Unions: A Great History

In 2019, we celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Minneapolis Federation of Teachers (MFT). I have been learning about that early union history. It was an interesting period, especially for women’s organizing. There were a lot of progressive organizations started around that time.

Out of all of the local unions started then, we are one of the few still in existence. St. Paul has us beat. Their local is number 28. Ours is 59. They were the 28th local of the American Federation of Teachers. Their first strike, in 1968, was before ours too. The Twin Cities have a great history of teachers’ unions.

Out of all of the local unions started then, we are one of the few still in existence. St. Paul has us beat. Their local is number 28. Ours is 59. They were the 28th local of the American Federation of Teachers. Their first strike, in 1968, was before ours too. The Twin Cities have a great history of teachers’ unions.

Prairie Roots

My mother was born on a homestead on the prairie, just across the border in South Dakota. When my German grandfather retired from farming, he turned the farm over to his oldest son and moved the family to Big Stone City, South Dakota, at the bottom of Big Stone Lake. ‘City’ is a stretch—they never had more than 500 people. There were mostly Germans in the area. My grandfather bought an abandoned Baptist Church out there, big enough for his eleven children.

I’m named after my grandmother Louise, who ran a teacherage–housing for teachers, on the second floor of the converted church. The school was right behind the house , across my grandmother’s garden. They came out on the railroad and stayed there. The farmer with the nicest buggy would go to the nearest train station in Montevideo and pick up the teachers. I tell that story often, because it is illustrative of a time when teachers had intimate contact with the community in which they taught.

Of my grandparents’ eleven children, eight were girls, so the girls became farm hands, but they also had outside jobs. The four oldest worked to fund the youngest ones so they could go to college.They were the only telephone operators in Big Stone City, from the day they company began, until it closed.

My mom, Flora, was the youngest sister. She went to college in Naperville, Illinois, to become a teacher. Two other sisters earned their degrees there. One of the older sisters drove them to Naperville and back in an open touring car. After my mother got her degree, she taught in Dilworth MN, before accepting a job in Wilmar, MN, where she met my dad.

Iron Range Roots and Union Bloodline

My dad, Millard, grew up on the Iron Range, in Proctor, Minnesota. His folks emigrated from Sweden for religious reasons. Sweden would have required them to be married in the State Church instead of their Swedish Baptist Church where my grandmother worked. They came to the US to be married. My Swedish grandpa worked on the Duluth, Mesabi, and Iron Range Railway, running ore trains to the Duluth harbor. He was always proud that he never dropped an ore car off the dock into Lake Superior.

My grandma was a really jolly person and a great cook. They lived in a house owned by the railroad. My dad was an only child. He went to Denfeld Junior College—it is now a high school — got his two-year degree and went to teach at Wilmar. Dad’s politics were influenced by his parents Swedish Social Democratic beliefs in good government, paid for by the citizens to provide birth to death support systems for all. I guess I learned most of my social justice beliefs from him. Ancestry.com should started tracking union blood. I think my dad and I both got ours from my grandpa, a leader in the railroad union.

My parents fell in love while working together at Wilmar High School. They couldn’t get married publicly, because then my mom would lose her job. Only single women could teach. So they went out to South Dakota, to the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate Reservation and got married there. Neither the state of South Dakota, nor Minnesota have any record of their marriage. I always wondered why they didn’t celebrate their anniversary. I just recently put it all together.

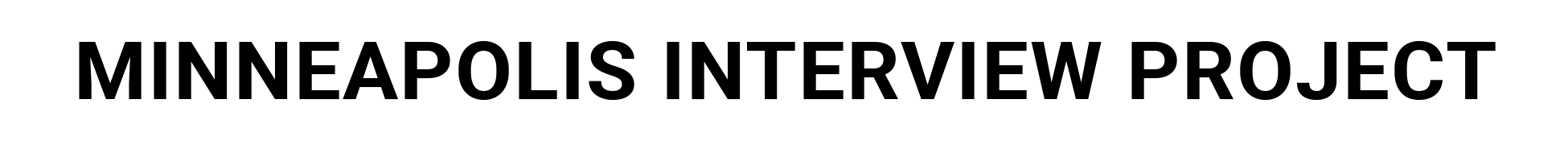

I was born in Ortonville, MN, because my mom wanted to be home with the support of her sisters for my appearance in the world. Ortonville is just across Big Stone Lake where the Richert house with the teacherage was located. My dad worked at the local grain elevator for the summer.

Soon after, they moved to Minneapolis, and my dad got his master’s degree at the University of Minnesota and was ABD. He became a 9th grade civics teacher at Phillips Junior High, on 13th Ave S and 24th St, one of the early schools to have a diverse population. It fed into South High School and was the school for most of the Native American kids in Minneapolis. Dad stayed there, teaching in the same classroom for the next thirty years. I’m sure he is rolling over in his grave that we don’t teach civics anymore.

When they tore Phillips down—which was a dumb idea—they decided to use a wire and pulled the wire through the building with a dump truck, but it didn’t work. People said, “See, you shouldn’t have taken it down. It didn’t want to go.” Only the pool building remains.

Dad didn’t make enough on a teacher’s salary, to allow mom to stay home and raise kids. During the first couple of years teaching in Minneapolis the School Board reduced teacher pay at the end of the school year . They said they didn’t have enough money to pay the amount in the contract. Actions like that tend to radicalize workers. To make ends meet, after his day at Phillips Junior High, Dad drove a few blocks and worked as a tool grinder. He had two eight-hour jobs his whole career. He was a member of the machinists’ union and the teachers’ union. During winter breaks he worked at the Post Office and summertime he worked for Brinks Armored Car Service, until one summer when we stopped in Detroit on our way from visiting my aunt in Cleveland and Dad stopped at the Brinks Office to inquire about their union. When we got home he found out he was fired for inquiring about organizing a union.

My mom taught English at Southwest High after we John and I graduated. She was head of the English Department and advisor for the student paper. Like mother, like daughter. We were on strike together in 1970. She did picket duty at the delivery entrance to Southwest. She would tell of how six big male coaches would meet and drive together in one car to cross her picket line. “those big lubbers were afraid of me,” she would joke.

When my parents first moved to Minneapolis they lived in an apartment at 2nd Ave South and 32nd Street. David Roe, President of the Minnesota AFL-CIO also grew up ia couple blocks away. “It was a poor neighborhood then” David told me. I still exhibit the habits of those Depression years. I call it frugality. My friends call it cheap.

The first years my parents were in Minneapolis was 1936, the hottest summer on record. One day it got up to 108—and weeks of 100 degree temps. Those brick buildings without air conditioning were god awful. My folks slept in Powderhorn Park that night. Their apartment building was later sacrificed to build the 35W. freeway.

My folks finally saved up enough money to buy the home in SW Minneapolis where I now live. It cost $7,500i n 1944, (which is half the cost of my annual property taxes today. This is my forever home. I plan to age in place.) My bother John was born that year, in a later October blizzard. Dad drove mom to the hospital by following the tracks of the streetcars that had snow catchers on the front, plowing the snow ahead of them. They made it to St Barnabas Hospital in time.

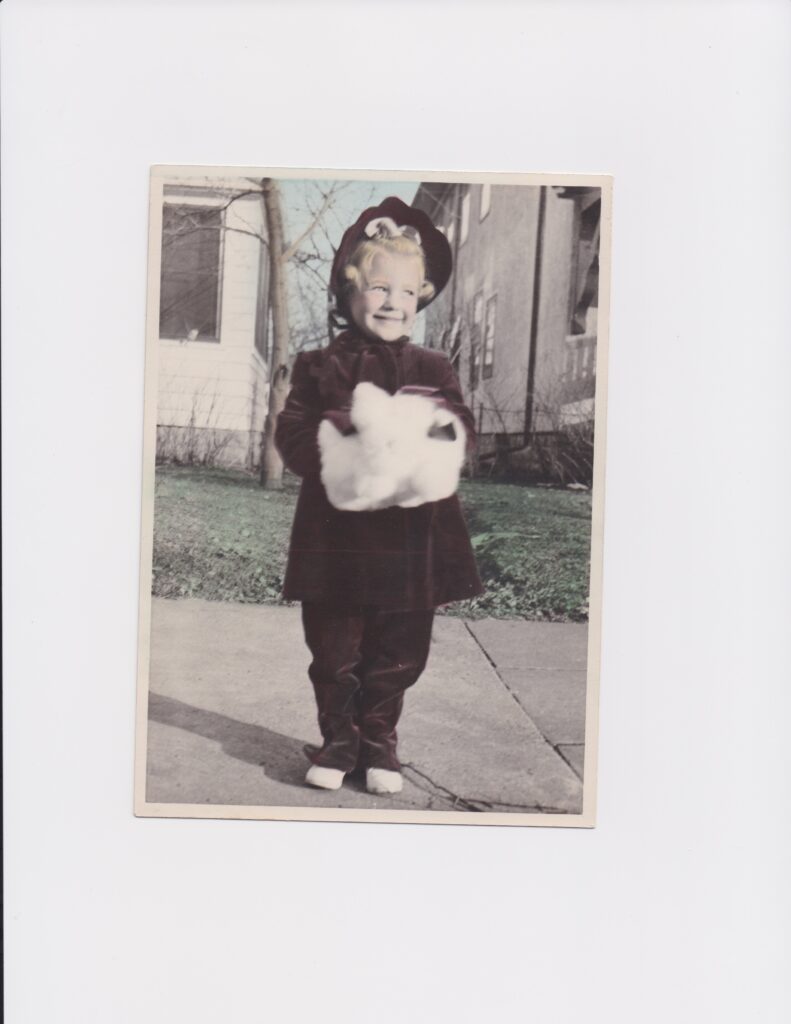

My brother John inherited my folk’s traits of caring, compassion, attention to detail, and service to others in his career, as a hospital pharmacist and church organist in Moose Lake, MN. When we were kids, our family was actively involved in the Minneapolis Figure Skating Club. My dad was President for a few years and my mom sewed costumes. I still have the stuffed teddy bear costume my brother wore when we skated to “Teddy Bear Picnic.” It was a wonderful time of togetherness as a family. We also took a family road trip every year, usually to a National Park. We leaned about the beauty and history of our country.

With the Rookies, Leading the 1970 MFT59 Strike

I did balk at becoming a teacher. My mom said what lots of mothers said: “Get the degree and you can always fall back on it.” I got a B.A. and a B.S. from the U of M. In 1970 I was a rookie teacher, only in my third year, still on probation. Back then, teacher jobs were everywhere, because there were so many kids. Minneapolis Public Schools (MPS) had 66,000 kids then—exactly twice what they have now. Those demographics gave the MFT the power to strike. If we lost our jobs we could find other ones.

There was a strict no-strike law then. It was easier for us rookies to break that law than it was for the older teachers who had invested in pensions, who had seniority and were heads of households. Our union president resigned the week before the strike, and Norm Moen was elected President of MFT 59, AFT, AFL-CIO. He and Dale Holstrom, Union Business Agent and the Executive Board led us out on strike after the membership voted to go out against the law.

Those who didn’t go out on strike were members of City of Minneapolis Education Association, CMEA—an NEA affiliate. It was the organization that represented Minneapolis teachers prior to the collective bargaining election that was won by MFT. They purported to be more professional and didn’t believe in striking. We went out on “truth squads,” knocking on doors, trying to convince families we were doing the right thing. It probably was a good strategy, one that the labor movement uses today, to knock on doors and connect with people.

Going out on strike in 1970, I learned to speak up. I had the greatest time. I was teaching at Ramsey (now Justice Page). I would walk the picket line in front of the driveway where the trucks came in. The Teamsters honored our picket lines. That felt really good. I kept a little make-up bag in the car in case I got arrested. Many of us union high school teachers would go and picket at elementary schools after our shift at our own schools. I was in great shape from all the walking.

We had our Ramsey and Washburn picket headquarters at 49th and Nicollet S. Almost every afternoon we would have a rally at the Nicollet Hotel downtown. Occasionally we had bigger rallies in front of the district office on 807 NE. Broadway.

The Minneapolis Board of Education was made up mostly of business leaders then. The President of the Lutheran Church was on it, and other male civic leaders. There was only one member who was sympathetic to teacher issues.

Our negotiating team had only one woman, Colleen Schepman. After the strike had been going on for a week or so, the Governor was talking about calling in the National Guard. The board invited us to the Minneapolis Club to negotiate. At that time women weren’t allowed in the front door of the club. (Muriel Humphrey was the first woman member of the Minneapolis Club, and that was after Hubert died). So the whole team went with Colleen to the back door. But she still had to sit in the basement and the team sent messengers back and forth to her.

We negotiated for equal prep time for elementary school teachers and smaller class sizes. Mostly, we gained respect.

Aftermath of the Strike

Because of the no-strike law, we all lost our jobs. We had to get legislation passed to get our back pay, our jobs back and our pensions restored, so we did that by advocating and organizing through legislative and legal systems. It took four years. As a result of that strike, the Minnesota Public Employee Labor Relations Act (PERLA) became law. it still survives—one of the most progressive labor laws in the country—protecting collective bargaining rights for public sector workers. In Michigan and Wisconsin, they lost those protections in recent decades.

After the strike, one of our MFT members—Lyndon Carlson—was elected to the Minnesota Legislature. He is now the longest surviving member of the MN house—48 years. It was an exciting period to be a part of the union. Augsburg History Professor William Green contends that due to our strike, the Citizens Alliance—the business alliance the Teamsters fought in 1934 Trucker’s strike—finally lost control of the city. He is the historian. I’m not going to argue with him.

Integration Efforts and Riots at Ramsey and Washburn 1972

I taught English at Ramsey Junior High (now Justice Page Middle School). The district, led by a group of parents, was instituting BAR: the integration of Bryant, Anthony and Ramsey. Anthony and Ramsey became 7th and 8th grade and all the 9th graders were at Ramsey. We loved it. We were doing creative things, with those 1000 9th graders. But then the School Board needed to close a high school. That is a hard thing to do, so instead they closed Ramsey and sent the 9th graders into the high school, eliminating our wonderful program. I followed the 9th graders to Washburn High School.

In 1972 Black students rebelled at Washburn. I looked out my window and there was a double cordon of police heading toward the school. The kids closed off 50th Street. The police officers sent dogs into the school. One of the students parked his car by the front of the school, popped the trunk and handed out baseball bats to the students. One teacher got injured.

Becoming a Union President

It wasn’t too much time before I ran for a union position: the district-wide professional development committee. I lost. I didn’t realize the election was stacked. It was a good lesson to learn early: how to count. If you want to get something passed, you better figure out where your support is. Jim Pearson, our MFT lobbyist, and a social studies teacher, taught me to always count the votes.

In 1984, a group of us decided to oppose the MFT59 union president. They decided to run me. No one had ever run against a sitting president before. Turnover happened when someone retired or decided not to run again. I ran against Bob Rose. It is in my mind today, because tomorrow is Bob’s funeral. He was chair of the strike team and he was wonderful at that. He just wasn’t as politically adept at being president.

I won and was president for 22 years, until 2006.

Starting a Master’s Degree Program with the Union

When I was president of MFT, I started a master’s degree program for MFT teachers through St. Thomas. Elementary teachers didn’t want to get a master’s in a subject matter. We developed a degree in “Curriculum, Instruction and Professional Leadership.” It was for all grade levels. We held the classes at the MFT offices. Free parking, good classroom space. And we fed them. We got a cut from U. of St Thomas on tuition because we did that. I got my master’s degree from my own program. (I’m still debating if I should get a doctorate before I’m done.)

By the time the program ended, we had gotten over 500 teachers master’s degrees. For them that meant they jumped several lanes—an instant raise. They felt good about getting a master’s degree they could use. St. Thomas taught half the courses and union staff taught half the courses. We taught Professional Development, Organizational Change, and Educational Reform—stuff that teachers said was enriching for them. They were having discussions with different grade levels, with their own colleagues. A cohort from Patrick Henry High school decided to do the program together. As a part of their degree they designed a teacher support and preparation program at Henry. I got some support from the superintendent at the time, and a grant from the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), and they started a professional practice school at Henry High School to train teachers. Shreds of it still exist today.

Working with Superintendent Richard Green

When I become president in 1984, Dr. Richard Green became the first African American superintendent. We started monthly meetings. The first time we met, he told me, “I have something to prove, being the first Black superintendent, and you have something to prove being the first woman president in a very long time, so it would do best to work together.”

He and I started a labor/management committee on professionalizing teaching. He bought the professional agenda. We included the chair of the school board at that time, She and Richard and I had a lunch together and pledged to work together for the kids. It was very tense between the union and the district before that. We had almost gone on strike again. There was distrust within the union as well. When I became president, we decided we needed to work as a team.

The first results of the L/M Committee was a mentor program with new teachers working with experienced teachers. There is a version of that stilling existing. Teachers inducting their own was the first step toward professionalizing teaching.

Pollyanna of the Prairie and the National AFT

In 1981, I ran for regional vice president of the National AFT and won. I had to present all my labor bonafides. I already had quite a bit of experience in the labor movement. I was already one of four women on the Minnesota AFL-CIO Executive Board. I was proud that a state labor leader referred to me as “tough as nails.” IAt various times I was a delegate, a VP, and an acting President of the Minneapolis Central Labor Union Council, now the Minneapolis Regional Labor Federation. I was also on the Minnesota Federation of Teachers Governing Board, and I served on the Twin Cities Labor Management Council and the Minneapolis Charter Commission. (Tom Dwyer with the Railroad Retirees, and I are vying for how many years we can serve. We both started as CLU delegates in 1975.)

The AFT was organized by regions across the country. I became regional VP for Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, and the Dakotas. I had that position for 25 years, through four AFT presidents. The New York folks are the majority in the AFT, and in charge because there are so many of them. I learned how to deal with New Yorkers early on. They called me “Pollyanna of the Prairie.” Anybody that knows me now think that’s the funniest thing they ever heard. The New Yorkers taught Pollyanna from the Prairie how to hug and kiss. Scandinavians don’t do that in public. We stay 18 inches apart. And so, I had to learn. It brought me out of my introverted shell.

The Saturn Experiment

From 1984 to 2000, the AFT developed a professional/labor management model of teacher/ union organizing, which I fully supported. I think it is a union model that can only work for teachers. For a short while, I thought it might work for other industries—but you know what happened to Saturn…

Saturn was a company that started with a new labor management model. For a while, I went around giving talks about their model—in my Saturn. Al Shankar, president of the AFT, took us to the Saturn plant in Tennessee. There were a lot of workers who were transplanted to their new plant in Spring Hill, Tennessee, from Detroit. Saturn was started by the president of the UAW and the president of General Motors. The two of them developed a solid trusting relationship and believed they could work better together—as every labor management team always believes. The punch line is the two of them died, and the relationship—and idea—died with them. But the corporate structure within General Motors put a stake through the heart of the model before the first car went off the line.

AFT President took us to Spring Hill three times, because he wanted us to see the just-in-time construction and the way the workers worked together. The parts came in the door and onto the car. A group of six workers construct the whole car together so they had ownership of that vehicle. They didn’t just stand in one spot and turn one screw. When it rolled off the line they would have a little ceremony. If someone on the team had an idea for an innovation they could go into a glassed-in space to explore their innovation. One employee redesigned the cart for their tools.

One of the visits we had was during the summer. Usually car companies lay people off in the summer until a new model is up. Saturn kept everyone on and the workers cleaned the place during the downtime so it was a spic and span factory. We interviewed the workers. I will always remember this woman who said “In Detroit, I was valued for what my hands could do. Here I am valued for what is in my head and in my heart.”

Whenever I tell the story I cry. That was the point of the trusting relationship. Saturn also redid the way cars were sold. In the dealership, you didn’t have to haggle. You go the bottom line price. When you bought a car there was a celebration. They gave you a calendar with your picture, and you got free oil changes and cleanings for the life of the car. In the fall they had reunions. Saturn owners like me would show up in Tennessee and have a party. I still have mine with 250,000 miles on it.

But there are no remnants of that labor model anywhere in the car industry.

Professionalizing Teachers

As a teacher’s union leader, Shankar was about professionalizing teachers, and I was sold on that idea. He said that teaching shouldn’t be organized any different than a law, medicine, or architecture. Teachers should be in control of their own work in schools. In his 1985 speech he outlined his professionalization vision.

The first wave of the professionalism campaign was instituting site-based management. Teachers, parents, and other employees were on leadership teams to make decisions about how the school was run. There were some buildings where it went really well. Not all of the principals could handle it of course. Those of us working as AFT vice presidents, who were sold on this model, had an unwritten contest with each other to implement the idea in our districts.

We created TURN: Teacher Union Reform Network.

TURN was a national group started by about 24 unions—the most progressive in the country—some little, some huge locals. They were from both AFT and NEA. I was one of the founding mothers of the group. It lasted 20 years. It expanded. The Regional TURNS survived for a while. As one example, we got teachers on interview teams to hire new teachers. A researcher in Milwaukee created an interview process that we used.

In Minneapolis I took Pawlenty’s idea of Qcomp, (quality compensation), raises for quality. I said we would try it because there was a lot of money with it. So we had peer review, leading to professional pay. I was on a pro-pay national task force. Then we began professionally developing and enhancing each other’s skills, and increased our pay for it. Teachers teaching each other. At one point we had twelve schools that were Teacher Centers. We had professional development sessions at Coffman Union at U of M. Teachers who carried out research in their classrooms presented their findings to their colleagues. An AFT Task Force I was on wrote a report about it: “Professional Development is Union Work.”

Through collaboration with the school district and contract language to support innovation, we started half a dozen experimental schools within the district, including Public School Academy, The School of Extended Learning, Chiron School in Community, Target School for parents working downtown, and others. None lasted more that a few years because the innovation and flexibility lost support of the District and they were sucked back into bureaucracy.

The One Thing We Forgot: Teacher-Powered Schools

We should have added teacher autonomy. That is what we forgot. Richard Fingersol writes about teacher-powered schools: encouraging and supporting teachers who are willing to work without administrators. You take away administrator costs and put those into teaching and get autonomy so that teachers do what they do best. That is what we should have ended with. There is a book published by Chuck Kirshner and Julia Koppich, the United Mind Workers describing how unions could provide the teachers with professional empowerment, by having the unions hire teachers.

My biggest mistake in my career was to not take the opportunity to do that for substitute teachers. At the time the district offered that to the union, the economy was really good. I chickened out because I thought, if they can’t find the substitutes, how are we going to find them. I shouldn’t have passed up that opportunity.

Thoughts on Teachers Union Organizing Today

TURN is still organizing at the regional level. I just learned recently, there is a new organization advancing the idea of moving into community organizing. Chicago Teachers Union was one of the first. Others are following suit. Working with community organizations is important. I don’t think it should be at the expense of helping teachers with their professionalism. We need to fight against a curriculum based on test-taking and recording. When you get a teaching degree, there isn’t a class in professional empowerment. There is no discussion or example of schools being professionally empowered and run. only top down, bureaucratic models. The union needs to care about empowering teachers. What is falling by the wayside is assistance to teachers to advance their teaching. The focus is now external. I worry about how many teachers are leaving, and telling their kids not to go into teaching.

During my generation, when women’s choices were limited, those who chose teaching were really the best and the brightest. Now those women are getting professional pay as doctors, or whatever. Teachers need to have that pay in order to attract the new innovative teachers.

Leading Retirement Labor Organizations

I am now involved in six retired workers’ organizations. Retirees want to stay active and make a difference. We organize around things we need, like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Health issues can lead to homelessness quickly. So housing and health care are our issues. We are in the political arena and are valued by the AFL-CIO because we are so active and good at it. The activism of retirees is recognized. In 2020, Governor Walz appointed me for another term on the Board of School Administrators, representing the public. I am steeped in union, education and public advocacy work.

Labor Chorus

I sang in high school. As an adult I sang in church choirs. I was excited to help organize the labor chorus. Reverend Barber, creator of the Moral Mondays campaign, came here from North Carolina because one of MFT59 members had a connection with him. MFT President Lyn Nordgren and Barber did a march down Nicollet Mall. He spoke at a forum and said “Movements run on song.” Wherever he goes, he has a musical director that leads people in song. I thought that was fascinating. Songs are powerful for inspiration and for messaging. Recently a few of us from the Labor Chorus went out to sing on the UAW picket line. There were only five striking workers there, and it was raining. But they sent a note later, saying how much it raised their spirits.

The MFT59 Strike of March 2022

Teachers don’t take to the streets easily. The members and leaders of the Minneapolis Federation of Teachers, Local 59, are as strong in 2022 as they were in 1970. Together, MFT members are working to strike a better bargain, one that improves the conditions under which our city’s children learn and our teachers teach. It’s a powerful action in support of Minneapolis families.

Teachers no longer have to worry about their strike being against the law. The 1970 strike was illegal— we risked going to jail for going on strike. The 2022 strike is legal thanks to the Public Employee Labor Relations Act that was passed because of our 1970 strike. Despite that difference, the issues are painfully similar— class size, support professionals to serve the students who struggle inside and outside the classroom, professional pay and respect for all MPS educators. Society hasn’t respected education or educators very much for a very long time. And we have two strikes, with 52 years in between, to prove it!

Following My Parents’ Footsteps

I am basically an introvert—so the personality inventories show. People don’t believe that. Going into a fundraiser, I feel very uncomfortable until I find a person I know. My dad, on the other hand, was fun, outgoing, and the hardest working person on the planet. My mother was always quietly helping people in trouble. She would hear of a person needing help, find out the problem and find a way to help, quietly, so no one ever knew. Fix the problem and then go onto the next problem. I’ve been trying to emulate them both, all my life. I hope they see me making progress toward emulating their unmatched work ethic, and selfless and quiet assistance to others.