At the Minnesota African American Heritage Museum and Gallery, we preserve, document and celebrate Black history, art and culture in Minnesota. We have a dedicated board and dedicated volunteers.

After the murder of George Floyd, people have been more focused on diversity and supporting Black-led organizations like ours, but it’s really a shame that a Black man had to die for people to see the value in Black history, art and culture. Also, I wonder, how long this is going to last. Is this substantive or a momentary change?

— Tina Burnside

Central Neighborhood Roots

I was born and raised on the Southside of Minneapolis, in the Central neighborhood. My mother, Dana Burnside, was from Iowa and my father, Bennie Burnside, was from Mississippi. They met in Iowa and moved to Minnesota. My mother was a vice president of a labor union and my father was an electrician. My parents have both passed away now, but my siblings and I still own the family home in the Central neighborhood.

I loved my neighborhood which was part of the historic African American enclave on the south side that included Bryant, Central and parts of the Regina neighborhoods, stretching from Lake Street to 42nd Street. Back in the day, it was one of the only places where Black people could buy houses in Minneapolis, because of restrictive covenants and redlining. It was a close-knit Black neighborhood amongst a larger white population. Today the area is more diverse with Hispanics, as the largest population, and Somali and Asian immigrants, as well as Blacks and whites.

When I was growing up there was a strong Black business district on 4th Avenue; a grocery store, a record store, barbers, beauty shops, night clubs, senior center and restaurants. The only business that remains on 4th Ave that was there from the 30s through the 70s is the Minnesota Spokesman Recorder.

Some studies show that closing neighborhood schools destabilize communities because schools are community anchors. I think the neighborhood is not as close-knit now because they closed Warrington Elementary, Bryant Junior High and Central High School. Closing Central High really took away the heart of the neighborhood. Central brought the neighborhood together for basketball games, football games, homecoming parades. It gave you a sense of pride and connection.

My brother went to Bryant Junior High, which is now Sabathani Community Center, but Bryant was already closed by the time I was of age, so I went to Ramsey—now Justice Page Middle School. My brother and older sister both graduated from Central. I went to Central High School for two years, before they closed it and I was bussed to Roosevelt High School where I graduated. My younger sister also graduated from Roosevelt.

A Curious Kid

A Curious Kid

I went to Lyndale Elementary School, one of the educational experiments in the 1970s. The school was round, rather than square. It didn’t have any walls. We had classes in pods. Our classes were mixed grades, first and second together, and third and fourth. It was unique. We called it the school without walls.

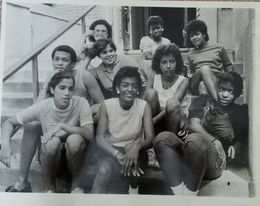

I was a very curious kid, interested in pretty much everything. I was always involved in something, learning something, trying something new. I played sports at Hospitality House, a youth center with facilities on the south and north side. I joined their basketball team at a very young age, starting in 3rd or 4th grade. Judge Pam Alexander was our coach. I think she was in law school at the time, because, you know, she grew up in the neighborhood.

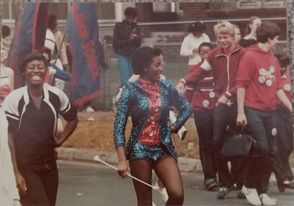

Hospitality House was like the Boys and Girls Club. They had one over South and one over North. The one on the south side was at 35th and Lyndale, I think. They had sports leagues—basketball, softball. In high school, I also played basketball and badminton. Minneapolis public schools actually had competitive badminton. I also ran track, but I didn’t really like running that much. Basketball was my sport. I was a majorette at Central and a cheerleader at Roosevelt.

Young Writer

I always liked to write as a kid. When I was in elementary school, the Minneapolis Star had a column they called “The Smile Factory,” where they would publish children’s works. They had a Halloween contest. My story about a haunted house won. I got paid and they published it. I liked seeing my byline. I decided I wanted to be a reporter. In high school at Roosevelt, I wrote for the student paper.

Urban Journalism Workshop

In high school, I participated in the Urban Journalism Workshop, which was designed to get kids of color interested in careers in journalism. You had to apply for it. I was selected. It was a summer program. Like other professions, journalism has historically not been very diverse. Newsrooms have not been representative of the community at large and most newsrooms are white. Representation is very important. If you don’t see someone that’s doing something that you’re interested in, then you don’t know if it’s possible, or even an option.

Through the Urban Journalism Workshop, I got to work with Black journalists. They would tell us about their careers. We learned all aspects of the trade, from photography to editing to writing. We did a series on teen pregnancy, interviewing different people involved: social workers, teachers, administrators, and actual teen parents. That was really great.

The program was at the University of Minnesota. We stayed in a dorm so we got to know the campus. We got U of M college credit, if you went to the U, you would have some credits going in. That solidified my interest in writing and wanting to be a reporter.

Becoming a Journalist

I went to the University of Minnesota from 1984-1988 and graduated with a degree in journalism. The U isn’t for everyone because it is so big, but I liked the large campus. The big classes didn’t bother me. I liked the different opportunities and wide variety a Big 10 university has to offer. The campus is a lot different now, after they built that stadium. I go over and I don’t even recognize parts of it.

While I was a student, I wrote for the Minnesota Daily and had internships at the StarTribune, Chicago Tribune, and the Milwaukee Sentinel. The Sentinel offered me a job before I graduated.

The Transformation of Journalism

I liked being a reporter but did not like the changes occurring in print journalism. The industry was going through huge changes while I was working at the Sentinel. Before cable news channels, newspapers could always hold their own against TV news, because we had the space to tell stories in more detail. I liked hard news stories, not fluffy features.

With the arrival of 24-hour cable news stations, print started trying to compete, so there was less of an emphasis on hard hitting news and more sensationalized stories. Today, a lot of newspapers have closed and the ones that are still open survive by having on-line editions. There’s less advertising so the papers are a lot thinner than they used to be. It’s sad to see the death of newspapers.

Discrimination from White Editors at the Milwaukee Sentinel

I left journalism because I just didn’t like the direction that it was going in. I also become dissatisfied with the lack of opportunities for Black journalists. When I was a reporter at the Sentinel, I broke the story of the serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer. It was a huge story, and I had a front page article in the paper about it. However, afterwards the white editors assigned the continuing coverage of the story to a white male reporter. I was furious and confronted the editor who had no real reason for the assignment, but to say that it was his decision. This would not have happened to a white reporter and was a clear example of discrimination.

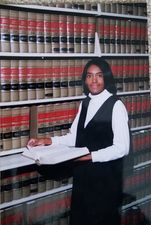

I still loved to write, providing information to the public, and telling people’s stories. But I lost interest in “journalism” as a profession. I didn’t quite know what else I wanted to do. A friend was planning to go to a law school fair and she asked me if I want to go. I was like, “Oh yeah, sure.” She ended up not going but I still went. I collected all this information from different law schools and then decided: law school is three years so maybe I’ll do that.

From Journalism to Law School

Law school is not usually something you do to pass the time away, until you figure out what to do, but that is what I did. I went to the University of Wisconsin Law School in Madison and graduated in 1996. I was fortunate that for both undergrad and law school I got scholarships and full rides.

I graduated and then I was like, OK, well I have a law degree, should I practice law or go back to journalism? I never planned to be a lawyer, but I started working with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and I have been doing that for 24 years. I worked for the EEOC in New Orleans, Milwaukee, Charlotte, and now Minneapolis.

Senior Trial Lawyer with EEOC

Senior Trial Lawyer with EEOC

I’m a senior trial attorney at the EEOC where we sue companies that discriminate against people in their employment on the basis of race, national origin, sex, religion, disability and age. Employment for most people is an essential and important part of their life. To some it’s what defines them, gives them purpose and gives them the financial means to support themselves and their families. When companies discriminate, it has a devastating impact on that person’s life and impacts society as well since this shatters the alleged “American dream” that the United States is built on. That premise that if you work hard, you can achieve anything in America. Well, that’s often not true for people of color in this country who experience disparate treatment and inequality. So being a civil rights attorney is fulfilling. I can do my part to fight against discrimination and get justice for people who have been treated unlawfully.

Becoming a Historian of the Minnesota Black Experience

I came back to Minneapolis, in 2013 to work in the Minneapolis EEOC office, when my mother was sick. When she passed away, I stayed. I’ve been here ever since. I began doing some writing for the MN Historical Society for their MNopedia page and then for the Hennepin History Museum magazine and that is how I became a local historian, writing about African American history in Minnesota.

A lot of museums are not interested in Black history. They’re more interested now than they were before, but I looked for ways to capture stories that were being lost. I had this History Harvest event where people from the community brought items from their personal artifacts and I would interview them and take a picture of them and the item and that would tell the story of their life, or their family or their community. It was a good tool for capturing African American history. A lot of our history can be found in individual stories and in items in people’s homes. These artifacts tell stories passed down for generations. But often, when the elder passed away those stories and the significance of those artifacts was lost.

How We Started the Minnesota African American Heritage Museum and Gallery

I was having this History Harvest event at a church on the south side, St. Peter’s AME Church, and Coventry Cowens came. I thought she was there to participate. She did bring something, and I interviewed her. At the end of the interview she said, “I’m trying to start up museum of Minnesota African American History, would you be interested in helping?” I said, oh yeah, sure, not having any idea what it takes to open a museum. So we got together, had these meetings, went around and talked to different people in the community, and talked to elected officials, trying to gauge the temperature of the community, their interest in a museum and what they would like to have in it.

There’s been several efforts to have a Black History Museum in Minnesota. Back in the 70s there was the Afro American Cultural Arts Center on the south side. (David V. Taylor papers at the MN Historical Society discuss this enterprise). Maybe ten to twelve years ago, Coventry was involved in an effort with Roxanne Givens to open the Minnesota African American Museum and Cultural Center. It had challenges and never really opened, but Coventry still had the dream.

And then Thor Company was opening a new building over at corner of Plymouth and Penn. We had a meeting with them, and they offered us a space. Since we didn’t have a space at the time, that became our starter space for the museum. We opened in 2018. We are in our third year.

Challenges of Running a Black Museum

It’s very challenging running any institution, particularly a museum, under any circumstance. It’s even more challenging if it’s a museum that’s Black-led and focused on African American history and our culture. Funders are not supportive of it. You have to jump through many more hoops than white-led organizations. Your requests are scrutinized more. We’ve had comments like, “I don’t know if we should give you this money because I don’t know if you have the capacity to manage that money.“ Like Black people can’t manage money? They don’t ask those questions of white-led organizations. They just automatically assume that they are credible and qualified.

After the murder of George Floyd, people have been more focused on diversity and supporting black-led organizations and black businesses, but it’s really a shame that a Black man had to die for people to see the value in Black history, art and culture. Also, I wonder, how long this is going to last. Is this substantive or a momentary change?

At the Minnesota African American Heritage Museum and Gallery, we have this motivation, desire and commitment to carry out our mission to preserve, document and celebrate black history, art and culture in Minnesota, and so we have a dedicated board and dedicated volunteers. Some volunteers have been with us from the beginning.

We just now got some grant funding, so we were able to hire three employees: a communication specialist, a community engagement coordinator, and a youth program coordinator. In order for the museum to be sustainable, build a legacy, and establish an institution in the Black community, we need permanent ongoing funding. We need to hire an executive director who can do many of the things that I’m doing. Thankfully we have Coventry who is retired and is able to be at the museum so we can have regular hours. We are open Tuesday through Friday, 1-5 and Saturday 10-1. Coventry is running the day-to-day operations.

Permanent Exhibit at the Minnesota African American Heritage Museum and Gallery

We opened three years ago. I’m really proud of what we’ve done in three years. We’ve put on over fifteen exhibits and programs. That’s a major feat within itself. We do both history and art.

We have a permanent exhibit called Unbreakable, celebrating the resilience of African Americans in Minnesota, that looks at the history from about the 1800s to the 1950s. It’s really popular. We won an award from the Minnesota Alliance of Local History Museums for that exhibit. Schools bring their kids to see it because they’re not getting that history in the schools. The comments that Coventry hears often from visitors are, “Oh wow, I didn’t know that. Why didn’t I learn that in school?” and “Where can I find out more information?”

We allow people to take pictures of the exhibit panels so that they can go and research more on their own. We encourage that, because we’re only giving like a snapshot, and we want them to go home and do more research.

We talk about early settlers. Most people had no idea that Black people were here before Minnesota became a state. We talk about some trailblazing women who did amazing things in Minnesota and on the national stage. We talk about Blacks who served in the military in World Wars I and II, when the military was segregated. We also focus on the Great Migration, which was the mass exodus of six million African Americans from the South to the Northeast, Midwest and West between 1916 and 1970.

When people think about the Great Migration, they think about Black people leaving the South for cities like Chicago and Detroit, because they have large Black populations, but the great migration route did include Minnesota. We look at places where people settled and how that impacted the population growth in the Twin Cities. I did some interviews with elders who were part of the Great Migration, leaving the South and moving to Minneapolis. We have this panel called Minnesota Voices of the Great Migration. My father and his family were part of the Great Migration. My dad’s parents were divorced and he, his mother and her sister and her kids moved from Starkville, Mississippi to Des Moines, Iowa. My grandfather (my dad’s father) and my great uncles moved from Starkville, Mississippi to Chicago. They all left the South in search of better opportunities in the North.

Rotating Exhibits of the Minnesota African American Heritage Museum and Gallery

Rotating Exhibits of the Minnesota African American Heritage Museum and Gallery

At the museum, we rotate other exhibits every three to six months. I’m also the curator at the museum. Currently we have an exhibit called, Gather In His Name, From Protest to Healing for George Floyd. It’s a black and white photography exhibit by local, photographer John Steitz. He went out to protests and up to George Floyd Square and took portraits of people who were involved in the movement. He contacted the museum and asked if we’d be interested in his photographs. They are really stunning—different from what the mainstream media would show, because the media only focuses on the burning of the precinct and property damage. They don’t focus on people and why people were so moved by the murder of George Floyd to leave their house during a pandemic to protest in the streets against police brutality and systemic racism

This exhibit humanizes the people that were involved in the movement. Along with the photographs we have a video from Unicorn Riot, an organization that does amazing work. They did a five-part series on the first five days of the Uprising. We have the first day. People are really intrigued by that video because, if the only place you get your news is from watching TV, all you’re going to see is burning buildings. They don’t see what led up to the police precinct getting burned down. We show that first day, in order to put things in context.

In June we opened a new art exhibit called The Absence of Justice. We have seven different artists involved in it, and we have pieces ranging from tapestry and ceramics to paintings, and a video from the Sounds of Blackness. That art exhibit focuses on the history of injustice in America as told through works of art.

I like to blend history and art together in some of the exhibits. We had an exhibit on the spiritual and cultural history of African American women wearing church hats. We had actual hats and we also had paintings and photography to tell that history. Last year we curated the BLACK LIVES MATTER mural that was on Plymouth Ave. We brought together sixteen brilliant and talented artists and they each painted a letter to create the mural. We had a permit from the City, but it was only for one day so the artists were amazing in their ability to paint a mural in 8 hours! People came out and helped artists with the painting. It was 100 degrees that day, but it was a beautiful community celebration to affirm that Black lives do matter and to show that the museum stands in solidarity with those fighting for racial justice.

So, we’re a very small museum, but we do amazing things. We have many ways for people to get involved. You can become a member, volunteer. You can donate.

More Than Just A Museum: A Community Resource

Since I don’t have a background in museum studies, I probably approach exhibits a little different than other museums. I draw on my background as a journalist, a writer and an attorney, focusing on research, fact-checking and making sure things are accurate, but also, with my journalism skills, I focus on telling stories. I don’t know the rules that may be out there about how you’re supposed to do things, and because of that, we are probably unique—a kind of a fresh first look. We don’t fall into this mold that other museums may follow.

The way I approach an exhibit is to think: what story do I want to tell? What facts do I want people to learn? What information am I trying to give people? I also want to make it entertaining. Because I am a writer, sometimes the exhibits get a little wordy. I need to edit myself. I have to remember that people are not coming to read a book. I’m working on that.

We see ourselves as more than just a museum. We display history, art and culture but we are also a gathering place for the community. We want people to feel that this is their museum. And so we ask, what would the community like to see.

We open up our space for community programming and participate in different neighborhood events. Before the COVID pandemic we used to have an open-mic poetry night. That was really popular. People could come out and express themselves, do spoken word or read poetry.

We also do partnerships with different organizations to reach broader audiences and get more done. We partnered this year with Black Fashion Week Minnesota, and we did a fashion show at our museum on the rooftop just a couple weeks ago. It was a really great event. Everybody had a really good time. We had a pop-up exhibit on the history of Black iconic designers like Willi Smith who did Willi Wear, and Fubu, Dapper Dan, and Ann Lowe, and then we had four local Minnesota designers who had pieces in the museum on exhibit of their fashions: Troe Williams of Vandalism Designs; Alexis Brazil of the Lexurie Collection; Kendall Ray of KD Designs; and Rammy Mohamed of Ramadhan Designs.

We see the museum as a place to provide a platform for Black artists, authors and creatives who do not get that opportunity at other museums. We provide opportunities and a platform for them. We promote Black local authors and invite them to come read their books and do book signings.

We also have a Children’s Reading Circle. It is virtual right now, but before COVID we used to have kids come to the museum every Saturday, and we would have local Black authors or community members come in and read to the kids. Melvin Carter, the Mayor of Saint Paul, was a guest reader. Now that it is on-line, you can find those readings on the website. Coventry and I both feel that literacy is very important and so we wanted to introduce kids to books at an early age so that they would fall in love with books and reading. We give away free books to kids. Before COVID, we also had free art classes for kids during the summer.

We wanted to provide an opportunity to get high schoolers involved in the museum. We get a lot of little kids and we get 20-year-olds and up, but we don’t have a lot of high school students visiting. They have more important things in their lives, I guess. To get them interested, we got a grant from the Minnesota Vikings to have a Youth Curators Program this summer. We have twelve students this summer. They started in June and the program goes until the end of July. They come to the museum every Saturday to learn about the museum, Black history in Minnesota, and art. We have guest speakers. The students are learning research and writing skills. They’re making videos and doing interviews. They’re also learning about art and the role of art in racial justice movements. They are working on creating a history and an art exhibit with the theme of racial justice which will be displayed in as a pop-up at the museum starting in August.

We’re always trying to provide opportunities to people who you normally don’t see in museums. We are trying to get more Black people involved in the museum field and let them know, you don’t have to have a background in museum studies or history. Neither Coventry nor I have that type of background and we are running a museum so they can do it too. Our message is, if you’re interested, there is a place for you.

We have four artists who are doing a nine-month paid artist-in-residency at the museum and a history fellow. The artists’ and history fellow’s individual exhibitions will be on display at the museum in 2022. We got funding from the Transformative Black-led Movement for these programs. We also got some funding for the artists residency program from artists Ta-coumba Aiken and Seitu Jones.

Writing About Race, Plays, and a Book

I’m a playwright. I’ve written several plays that have been produced here and in other places. I write about Black history and culture, race and injustice. I wrote a ten-minute play called Just a Rope. It had to do with lynching. It is set in the 2000s. A cleaning crew in an office building, comes upon a noose. White people see it as a rope, but Black people see it at as noose. The play is about how people view things very differently based on their perspective and their history.

I wrote another play called Kinks, a couple of years ago, before the pandemic, that had to do with a Black woman who goes on a natural hair journey. The play explores the issues surrounding Black women and hair, discrimination and how the standard of beauty in America is based on the image of white women. The play focuses on dispelling the myth and false messages that society has created: that the closer a person is to white, the more beautiful they are. I want to show how Black women are rejecting this message and embracing our beauty and celebrating the uniqueness of Black women.

I also wrote a book called Have Mercy, back in 2002. The idea for it came when I was a reporter. I did a story about a young girl who shot and killed another girl for her jacket. Her defense always stuck with me. She said she had PTSD from growing up in a violent neighborhood and a violent family environment. I took that theme and wrote a book about race and the criminal justice system and how it treats juveniles. I explored the question, can people develop PTSD from growing up in a in a violent environment. Since then, there have been studies that show that African Americans have historical trauma from the legacy of slavery.

Still, you know, a lot of people want to say, “Forget about slavery, that was so long ago,” or “I didn’t have anything to do with it.” People don’t look at the legacy of slavery. It’s not like slavery ended and everything was equal. There was Jim Crow segregation. We still see the effects of discrimination and segregation in every aspect of society from housing and education to employment and policing, and this country never wants to deal with that. They say, that was in the past, just move forward. Or there’s this revisionist history about what actually happened.

So yes, I think there is historical trauma. We are never going to move forward unless we can actually acknowledge what happened to Black people in this country.

Juneteenth: More Than A Symbol

For Juneteenth this year the museum participated in a jubilee festival that Rose McGee put together over in Saint Paul. Before COVID, we participated in the one in Minneapolis.

My feelings about Juneteenth being a national holiday: I think it’s a good thing. It’s about time. But I also don’t want it to be a symbolic thing: like, lets pass this law and give them Juneteenth as a holiday. Then we don’t have to deal with issues brought up by the murder of George Floyd, and the George Floyd Criminal Justice Act. We don’t have to deal with the racial justice issues associated with the infrastructure bill. We don’t have to deal with harder issues like voter suppression and voting rights.

The real question about the national holiday is whether they are going to incorporate it into the curriculum and teach what Juneteenth is about. Right now they are trying to get rid of critical race theory because it makes white people feel bad.

Opal Lee has been advocating for a Juneteenth national holiday for years. It’s a good thing. Long overdue. The problem is, whenever something becomes a national holiday, it gets commercialized. There is already Juneteenth merchandise at all the big box stores. Juneteenth cookies. Next year it will be Juneteenth furniture sales. That’s the downside of it.

Minneapolis Policing and George Floyd Square

I don’t understand the thinking of the City Council, the Mayor and the police department. Let’s start with George Floyd Square. It seems that the city is always reactionary. They don’t consult with their constituents and the other people who are affected by it. Instead, they are thinking about what’s going to be politically beneficial. It’s been a year now since George Floyd was murdered. The streets been closed for a year, and they still haven’t figured out what they should do.

I don’t understand why the city can’t sit down and have an honest meaningful conversation and listen to what the activists and the community are talking about. The activists have put forward these demands. Some of them are things the city has no authority or control over, so they should just tell them that, so it’s not a point to be considered. Other things the activists are demanding are reasonable, and within the city’s authority and control, and so the city should work with them on those.

You can’t just make a decision without consulting the businesses, the residents, and the activists. And you have to be honest. This recent debacle, when the city tried to open up 38th and Chicago at 4:30 in the morning, without telling activists, and then they said, “Oh no, it wasn’t the city it was AGAPE.” Do they think we are all stupid? AGAPE can’t just call up public works and get them to remove intersection barriers without city approval.

They have to come up with a solution that will open up the intersection but also respect the activists and create a permanent memorial for George Floyd. The city can’t just wash their hands and say its AGAPE now.

That’s my neighborhood, where I grew up. I used to be on CANDO’s board. I know something needs to be done, taking into consideration all of the numerous parties. Not everybody is going to get everything, but you have to meet people in the middle somewhere.

The city is also not thinking about the black businesses who are still there, trying to hang on. In Uptown they are willing to do all kinds of things to protect those businesses, but nothing to help the black businesses in George Floyd Square at 38th and Chicago.

It’s a tale of two cities. The city has all this money to develop north loop and downtown. And you know, southwest is always going to get their piece of the money. So what about Central and Bryant? Where is the money for economic development of Black businesses? Where is the money for creating living wage jobs? Where’s the money to assist with homeownership to build generational wealth? If taxpayer dollars are being invested in affluent and predominately white areas of the City, then taxpayer dollars can also be spent to address problems caused by systemic racism in Black communities.

They still haven’t done anything about police reform. Training is not enough because it’s a problem of police culture. Police have been trained with a mindset of “us” against the enemy. The community is not the enemy. I think there should be residency requirements because if police live in the communities where they work, they are more likely to be invested in that community and get to know the people of the neighborhoods they patrol. They are less likely to see people as a threat but see them as humans who are in need of their help.

There needs to be a shift in the public perception of the role of police. They are not trained or skilled to handle every issue for which they are called, particularly mental health issues. Also, maybe some non-violent issues get handled by restorative justice or community dispute resolution methods rather than police. Also, get rid of qualified immunity for police because that often shields officers from being held accountable for wrongdoing. If police officers break the law or engage in misconduct, they should be fired and held to the same standard as everyone else.

After George Floyd was killed, Black people are still getting killed by police. We had Daunte Wright, and then Winston Smith. Who knows what went on when Mr. Smith was killed. Nobody was there to film it. Law enforcement says one thing and the woman in the car says another.

We know we can’t trust law enforcement because they put out false statements initially, and then they backtracked. They said Smith was a murder suspect, but then they had to admit he was wanted on a warrant for possession of a weapon. Why should people believe the police when they lie? Remember, the police initially said George Floyd died from a medical incident during police interaction. Have we not learned anything in a year?

It’s just an ongoing struggle for justice. I have to give credit to those young people; they have a lot of resilience and a lot of endurance. They are staying on the front lines until they get resolutions, justice, and real change.