There was another, lesser-known Great Migration going on in the early 20th century–but in reverse, from the North back to the South, by northern-born African Americans seeking professional opportunities; and it included my aunt, my father, and my mother. My aunt, Martha Wright, graduated with honors from the University of Minnesota in 1938. When she asked the Minneapolis Superintendent of Schools for a job, he said to her face, “We don’t hire niggers.” However, historically black Savannah State College in Georgia recruited her to join its faculty, and she became a math professor in the deep South. There she met my Boston-born, college-educated mother, Mae Franklin Roach, who had been rejected by Boston white employers, but who had also been recruited by Savannah State. Completing this reverse migratory triangle was my father, Boyd Wright, a U of M grad like his younger sister, and who found likewise that no white-owned funeral homes in Minneapolis would hire him; so he too went south to Georgia, to work in a black funeral home in Atlanta. Aunt Martha introduced her brother to my mother, which became the backstory to me.

— John Samuel Wright

Fourth Generation Minnesotan

My name is John Samuel Wright the 2nd, named after my paternal grandfather, John Samuel Wright the 1st. I am a fourth generation Minnesotan on my father’s side. My mother’s family immigrated from Barbados in the West Indies at the turn of the 20th century. I was born into the Phillips neighborhood, and bred in one of the apartment buildings owned by my grandparents, near Franklin and Chicago, in 1946, while Harry Truman was President.

Education Pursued by Reconstruct-era Ancestors

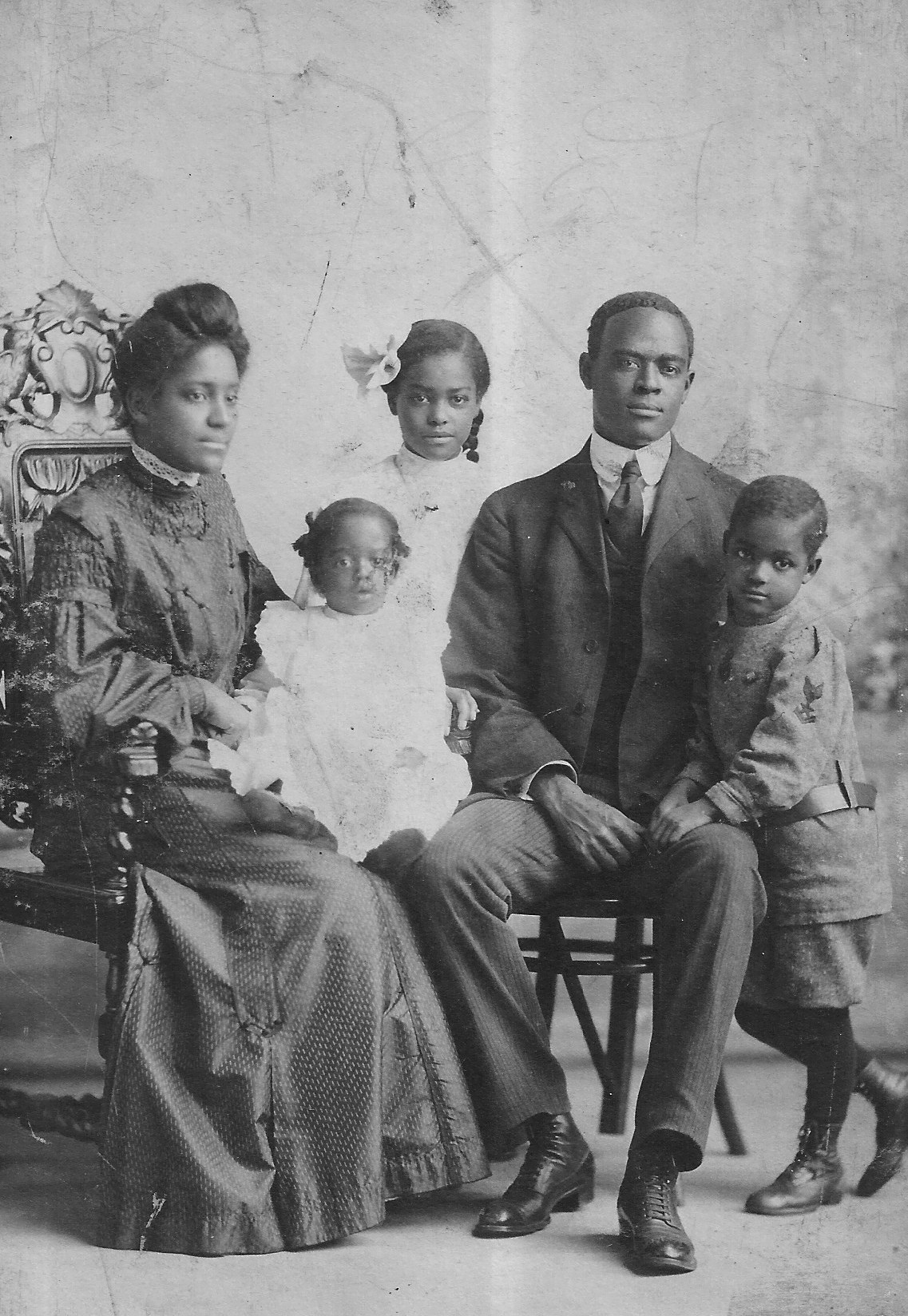

My great-grandfather, Thomas Wright, was a Buffalo Soldier in the 9th U.S. Cavalry from 1867 until 1898, when he fought in the Spanish American War in the Philippines and Cuba. His young son, my grandfather John, stayed in Kentucky with his mother until she died when he was five, after which he lived with relatives while his father patrolled the Western states and territories. Great-grandfather Thomas, who had no access to formal schooling, wanted his son to grow up where he could get an education, so he had him stay with his aunt and uncle for another five years, until he was able to remarry and gain access to education for his son.

Grandfather John, whom my father and his brothers always referred to as “Drap,” would tell his children about wanting to be with his father out West, and how at age ten, he got his wish. He described the grand trek he took from small-town Kentucky to St. Louis alone on the train, and then on stagecoaches to Flagstaff, Arizona, where his father met him with Indian ponies, and from where they rode by horseback to Fort Duchesne, Utah, the regimental home of the 9th.

The education he had been denied was vitally important to Great-Grandfather Thomas, but schools were only open on the military bases to officers’ kids. The famous West Point-trained Black officer for the 9th cavalry, Charles Young, told my Grandfather that, regardless of regulations, if he could pass an entrance exam, he could attend school with the officers’ kids. Young also skirted the rules barring fraternization between officers and enlisted men to make sure that my young grandfather, who was very bright and very eager, got enough schooling to graduate from high school at Fort Duchesne.

After my grandfather graduated at seventeen, he returned to Kentucky, where he attended a freedmen’s school, Eckstein Norton Normal School (later Eckstein Norton University). At eighteen he became a country schoolteacher. But the schools were not publicly funded—especially those for Black people—and my grandfather was often paid “in kind” with the parents’ commodities: corn, chicken, pigs, honey. He soon met my grandmother, Fannie Hall Wright; she was fifteen when they married.

Though Kentucky had not seceded from the Union, it was nevertheless a slave state; and after Reconstruction, the Jim Crow system was being constructed there at that time; and those oppressive pressures were increasing. So grandfather John and grandmother Fannie Wright decided to “go way out west,” as she framed it, to Minnesota during a period of added economic depression in the 1890s, following family elders who had come some years earlier during Reconstruction.

Jim Crow North in the 1870s

In that context, one of my grandmother’s uncles, George Hall, had come to Minnesota in tandem with a specific refugee stream—the Exodusters—who left Kentucky and Tennessee during the waning years of Reconstruction, led by a famous Black minister named Benjamin Singleton, who treated the enterprise as a prophetic biblical exodus. He led his followers west where there was still the possibility of getting frontier land for Black people to create and settle in independent Black communities in Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and elsewhere. Minnesota was an added natural route for those coming north via the railroads and the Ohio and Mississippi rivers.

My grandmother’s uncle, George Hall, had arrived in Minnesota by 1874, and was working as a barber. Back then, Black men still dominated the elite barber trade in eastern and southern seaboard cities, and they were doing so in Minnesota. George Hall became one of a group of six Black barbers, overseen by a senior black barber, working at the Merchants Hotel in St. Paul. In 1887, however, new white immigrant barbers from Germany and Ireland, unhappy with this situation, formed the first Minnesota barber’s union. But instead of forming an alliance with Black barbers, the new union excluded African Americans. They lobbied the Minnesota legislature to institute laws prohibiting barbering on Sunday, a prime business day for Black barbers. Those laws led to a police raid on the Merchants Hotel barbershop, the arrest of all the Black barbers, and their arraignment in court in St. Paul. I am still trying to recover those court records, but apparently, several of those barbers were driven out of the trade, including my great-great-uncle.

Uncle George subsequently moved to Minneapolis and lived with my grandmother and grandfather while re-establishing himself in a variety of other trades. My grandfather, John S. Wright I, like his Uncle George, also experienced racial barriers to his professional progress in Minnesota. The municipal school systems in Minneapolis barred Black teachers for decades. So he found work on the railroads and as a floor walker for a downtown department store. Ultimately, he settled into working for the Minneapolis U.S. Postal Service, a place where Black men with college degrees, barred by the color line from work in their proper professions, could find alternate employment.

Grandparents Build Black Religious and Civic Institutions in Minneapolis

My family on both sides, had a strong “race man” and “race woman” orientation.

My paternal grandparents were committed social community activists, helping to build local African American institutions. My grandfather was an early member of one of the first African American churches in Minneapolis: Bethesda Baptist Church, where he became the director of its educational programs and community outreach. My grandma was a member of St. Peter’s AME Church in southside Minneapolis, where I and my siblings were ultimately baptized.

My grandfather also became a member of the National Afro American Council, one of the first Black civil rights organizations created in response to the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court Case of 1896. The NAAC was a predecessor of the NAACP. The Black Minnesota community that my grandparents were part of played an important role in the formation of both national organizations.

Politically, my grandfather was always a Republican —in the party of Lincoln—while my grandmother was a more radical activist who allied with Black and cross-racial progressive organizations. She became the founding head of the Minneapolis chapter of the Colored Women’s Pioneer Economic Development Club. She organized fundraisers for the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, a radical Black union led by socialist A. Philip Randolph. I retrieved articles in Randolph’s New York newspaper, The Messenger, praising my grandmother and W. Gertrude Brown, leader of the Phillis Wheatley House in North Minneapolis, for organizing a fundraiser on behalf of the Brotherhood in 1927.

National Convention of Afro-American Council, held in St. Paul, 1902

In 1902, my grandfather helped Frederick McGhee, (who W.E.B. Du Bois would credit as the real initiator of the Niagara Movement that led to the founding of the NAACP), organize the biannual convention of the National Afro-American Council in St. Paul Minnesota. The convention was covered extensively in the local Black newspapers, particularly The Appeal, edited by John Quincy Adams. At the convention were W.E.B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells, Booker T. Washington, and T. Thomas Fortune. The convention had its final meeting and a grand ball, at the University of Minnesota campus.

Build Black Commonwealths or Pursue Civil Rights through Social Reform? A 1901 Debate

A year earlier, in 1901, my grandfather, as head of education programs for Bethesda Baptist Church, organized a formal public debate, with three University of Minnesota Black law students, on the question: Are Afro-Americans better off seeking to establish independent Black Commonwealths within the boundaries of the United States, or seeking redress of their citizenship rights issues through conventional social reform organizations and movements?

They assembled a panel of judges that included leading Black lawyers and clergymen. The debate was covered in the Minneapolis Journal, so we have at least a summary. My grandfather and a Black lawyer and U of M graduate named Harvey Burke, argued in the affirmative: create a Black commonwealth. But the audience agreed with the other debate lawyers, T. McCants Stewart and Joseph Reed, who argued for more conventional progressivist electoral reforms.

Acquiring Land in Minneapolis

Given his experience on the western frontier, it makes sense that my grandfather sided with the independent commonwealth-building perspective. From the moment they arrived in Minnesota, he was interested in land ownership. Once he and my grandmother acquired a home for their family, they went about acquiring apartment buildings in Minneapolis that served as homes for other Black families. In 1916, my grandparents also acquired a truck farm in Robbinsdale to sustain their growing flock of seven children.

Sisters of the Mysterious Ten

Meanwhile my grandmother, whip-smart, self-taught, and supported by her husband, had become a leading social activist within a circle of local Black female groups and societies, taking leadership roles in many of them. She became a member of the Order of the Eastern Star, the women’s auxiliary of the Prince Hall Masons. My father remembered her also being a leader of the SMTs – Sisters of the Mysterious Ten, a women’s auxiliary of a Kentucky-based fraternal organization, who wore gloriously colorful robes. Their superintending male counterpart was the United Brothers of Friendship.

During the post-Reconstruction era, emancipated Black folk formed all kinds of organizations. Modeled on groups like the Odd Fellows and the Shriners, the United Brothers and the Sisters of the Mysterious Ten were quasi-secret societies spread by the Kentucky Exodusters moving to Missouri and Texas and other points west and north. The SMTs were recreating the social life of small-town Kentucky Black women in their new Minnesota home.

Grandparent’s Properties Housed Leading Black Minneapolis Families

As I said, my paternal grandparents had seven children, among whom my father, Boyd Wright, was the youngest of five brothers. He had one older sister, Johnsie, and one younger, Martha. He was born in 1916, the year the family purchased the farm in Robbinsdale. They continued to own apartment buildings in Minneapolis: one in the Phillips neighborhood, at 911 East 22nd St. and the other on 4th Avenue and 24th St. South, two blocks from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

Both apartment buildings became the residences of leading Black families in Minneapolis. Members of the family of Cecil Newman — founder and editor of the Minneapolis Spokesman Recorder, lived at the 4th Avenue building. The Phillips neighborhood building became the home, for a while, of civil rights icon Mathew Little, and of the Curtis and Mildred Ewing families. Matt Little would become a leader of the Minneapolis NAACP for decades. Curt Ewing was a leader in the local Black Bahái community.

(People don’t realize that the Bahái movement, which began in the US in the 1910s, was at the outset a heavily African American ecumencial religious movement. About a third of the Bahái community today is Black. The Bahái were an important part of my development early on, in terms of my awareness of a spectrum of religious possibilities.)

My grandparents also provided a parsonage for Bethesda Baptist Church in the house they owned on 27th and 11th Avenue South. Amazingly, my grandparents, who came to Minnesota with nothing but the clothes on their backs, managed, through hard-working diligence and entrepreneurship, to create a stable, prosperous base for their family and their community. I have photos of community gatherings that took place at my grandparent’s farm in Robbinsdale. In those days the closest streetcar to the farm ended about three miles away in mainstreet Robbinsdale. You had to walk the rest of the way. Still, people came to enjoy the community my grandparents fostered.

Boston Barbadian Mother

My mother’s background was much more economically precarious than my father’s. She was born in Boston of Barbadian ancestry. Her people came to the U.S. during the Caribbean immigration wave of the 1910s that brought people like Marcus Garvey to America — Black people leaving the Caribbean because of the economic distress created by British, French, Spanish and Dutch colonial empires, and the displacement caused by rapid industrialization of the old slavery-based agricultural economies.

My mother’s mother, Emma Franklin Roach, was a seamstress; Mom’s father, Japheth Nathaniel Roach, was a printer. But Mom’s family soon became impoverished when her father died soon after arriving in the U.S., leaving her mother with seven young children. She remarried a Black American who was a drunkard, a wife beater and a child abuser. My mother and two of her siblings were thrown out of the house by that abusive stepfather after they tried to intervene when he was beating their mother. They were taken in by a Black Boston minister, the Reverend Oliver B. Quick and his wife who became their adoptive parents.

Boston Jim Crow

Thanks to her adoptive family, my mother managed to get a full education, went on to business school and trained as an executive secretary. But Boston was notoriously racist and my mother, and most other Black professionals in the city, were barred from practicing their certified occupations. So many migrated to other parts of the country to pursue their careers. My mother was ultimately recruited by the President Benjamin Hubert of Savannah State College in Georgia, to become his Executive Assistant. Mom’s adoptive brother, Charles Quick, also experienced Boston-style Jim Crow in his Massachusetts hometown. He graduated from the famous Boston Latin School with honors but went south to attend an HBCU, before returning to finish Harvard Law school in the 1930s, during a period when Black students were barred from Harvard’s dormitories and fraternities.

Uncle Charles’ Harvard roommate was Oklahoma-born John Hope Franklin. Through this connection, the legendary historian became a family friend and a mentor and hero to me. Uncle Charles and John Hope Franklin devoted their careers to “raising the race,” and both joined the NAACP’s legal defense team in the famous Supreme Court cases addressing discrimination in American education. While serving on the faculty of the Howard University Law School alongside legendary Charles Hamilton Houston, Uncle Charles Quick helped litigate major education inequity cases during the 1940s and 50s and was the evidence specialist on Thurgood Marshall’s team presenting for Brown v Board in 1954. He ran the Moot Court exercises at Howard Law School, where Thurgood and all the team members practiced their upcoming presentations before the U.S. Supreme Court.

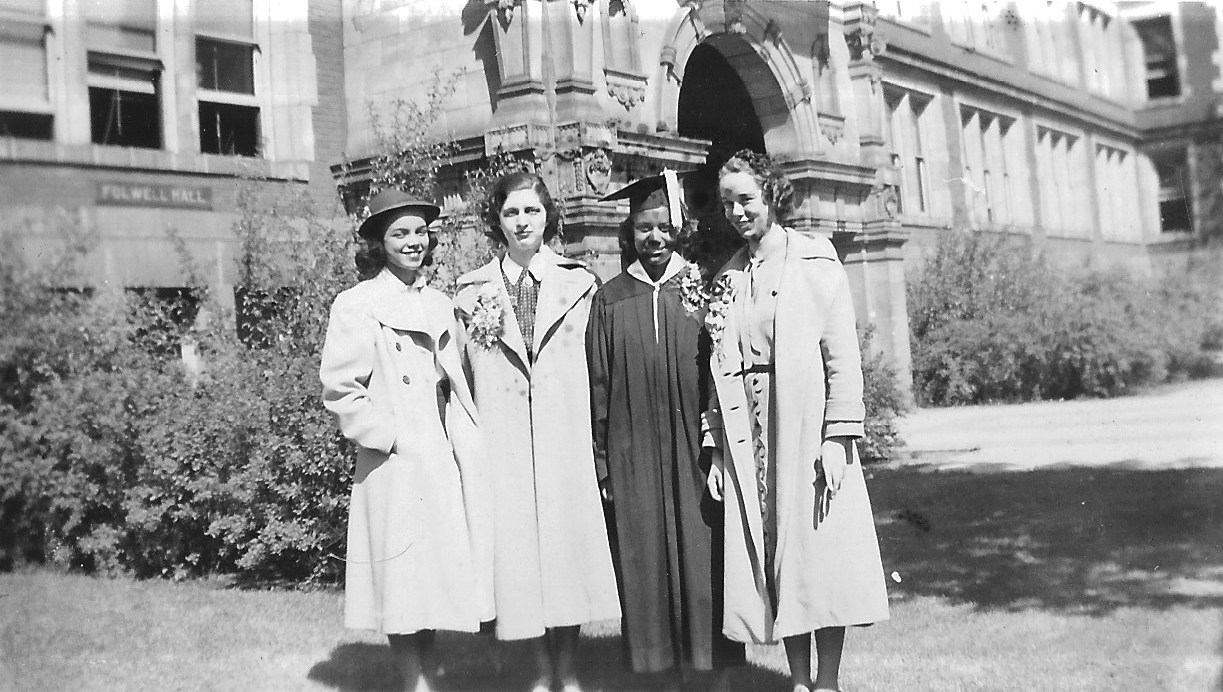

Aunt Martha, Valedictorian of North High

Soon after arriving in Savannah in the late 1930s, my mother met a newly recruited mathematics professor named Martha Wright. My father’s younger sister, born in 1918, was a brilliant scholar, who went to elementary school in Robbinsdale, where she was the best student in the district, and then North High School in Minneapolis where she was the class valedictorian. She skipped two grades and graduated from high school at the age of fifteen in 1934, alongside my father. At that time, North High was a school largely of white immigrant groups–Germans, Scandinavians, Italians, Jews, Anglos and only a handful of Blacks. The administration was so non-plussed to have a Black valedictorian that they took the counter-measure of designating a second valedictorian, who didn’t have a straight A average like my aunt, but who was white and male. Decades later, when my aunt and father went to their 50th class reunion at North High, classmates were still asking, why were there two valedictorians?

Back in the 1920s my grandfather had sent his older sons south to Fisk University an HCBU and Du Bois’s alma mater, in part because in 1923 the University of Minnesota had allowed a KKK float, with robed, shotgun-carrying riders, in its homecoming parade. That was in the wake of the Duluth lynching of Black circus workers just three years earlier, two of a series of incidents that made it clear to many northern African Americans that if they wanted their children to have optimistic attitudes about their life prospects, and a degree of safety, they were better off at independent Black institutions in the Jim Crow South.

During the Depression years, that calculation changed. My father and aunt both enrolled at the University of Minnesota. Aunt Martha became the only Black student in the School of Technology, which enrolled only five women students in 1934. My father became the only Black student in the School of Mortuary Science. Lotus Coffman was the President of the University then. My aunt and father became members of the very first Black student organization in 1936-37: the Council of Negro Students, created in opposition to Coffman’s policies. A notorious racist who had come of age in KKK-infested Indiana, Coffman supported the social segregation of African American and Jewish students in separate housing together with limiting the number of Black students allowed on campus.

Aunt Martha became President of the Council of Negro Students; and she was also President of the AKA (Alpha Kappa Alpha), the Black sorority on campus, which prided itself on having the highest grade-point average of any sorority or fraternity on campus at the time—campus Jim Crow policies notwithstanding.

Jim Crow North Brings Parents Together in Savannah

In 1938, my aunt went to the Minneapolis Superintendent of Schools to ask for a job. She had just graduated with honors from the School of Technology and the School of Education. The Superintendent looked her straight in the face and said, “We don’t hire niggers.”

With no apparent teaching prospects and amid the depth of the Great Depression, Aunt Martha stayed on at the U and got a master’s degree. The U of M had a kind of subterranean relationship with HBCUs. The same President of Savannah College who had recruited my mother, had completed a master’s at the University of Minnesota School of Agriculture in the 1920s, and he continued to have links to the U of M. He recruited Aunt Martha to come to Savannah State College to teach math, where Martha and my mother became fast friends.

My father also graduated in 1938, from the School of Mortuary Science, but he too couldn’t find a job in his profession locally. None of the white-owned funeral homes in Minneapolis would hire him, so he went to Atlanta, Georgia, to work as an associate mortician in a large Black funeral home there. Ultimately Aunt Martha introduced him to my mother, Mae Franklin Roach, her colleague and best friend at Savannah State, which supplies the back story to me.

World War II. No Double Victory

At the start of WWII, my father was shipped off overseas, and from 1942-45 he served in Germany, Italy, and North Africa in the Jim Crow U.S. army. He had some horrific stories to tell about boot camp training in the deep south before being shipped overseas. When he returned years later at the end of the war and deplanked, he got off the boat in Virginia and was immediately insulted and called a “nigger” by white folks.

After the war, my parents decide to come back to Minnesota to help out my grandfather, who was ailing. All the other siblings except one, my Uncle Frank Wright, had left Minnesota to seek their fortunes elsewhere. My father agreed to help maintain the farm and manage the apartment buildings in town. He couldn’t get bank loans to start his own independent funeral home, or a license from the Minneapolis City Council; so he did what his father had done and went to work for the U.S. Post Office.

Youngest Years in Phillips Neighborhood

After the war, my mother became a housewife, birthing four children in succession; me first in 1946, my sister Beryl in 1948, my brother Boyd Jr. in 1950, and my younger brother Charles in 1954. I, Beryl and Boyd Jr. were born into the Phillips neighborhood. I started elementary school at age four, at the old Horace Greeley elementary school, and was there until the end of second grade. My mother, who was a great lover of books and reading, taught me to read before I started school. I spent the first seven years in a central Minneapolis neighborhood that was a cultural amalgam of white and Black folks, Native Americans, Hispanics, Asians, Jews, and so on — a very mixed terrain – still mixed today, although a little different combination of cultures. ButI have no recollection whatsoever, of racial conflict or racial epithets targeting me during those early years.

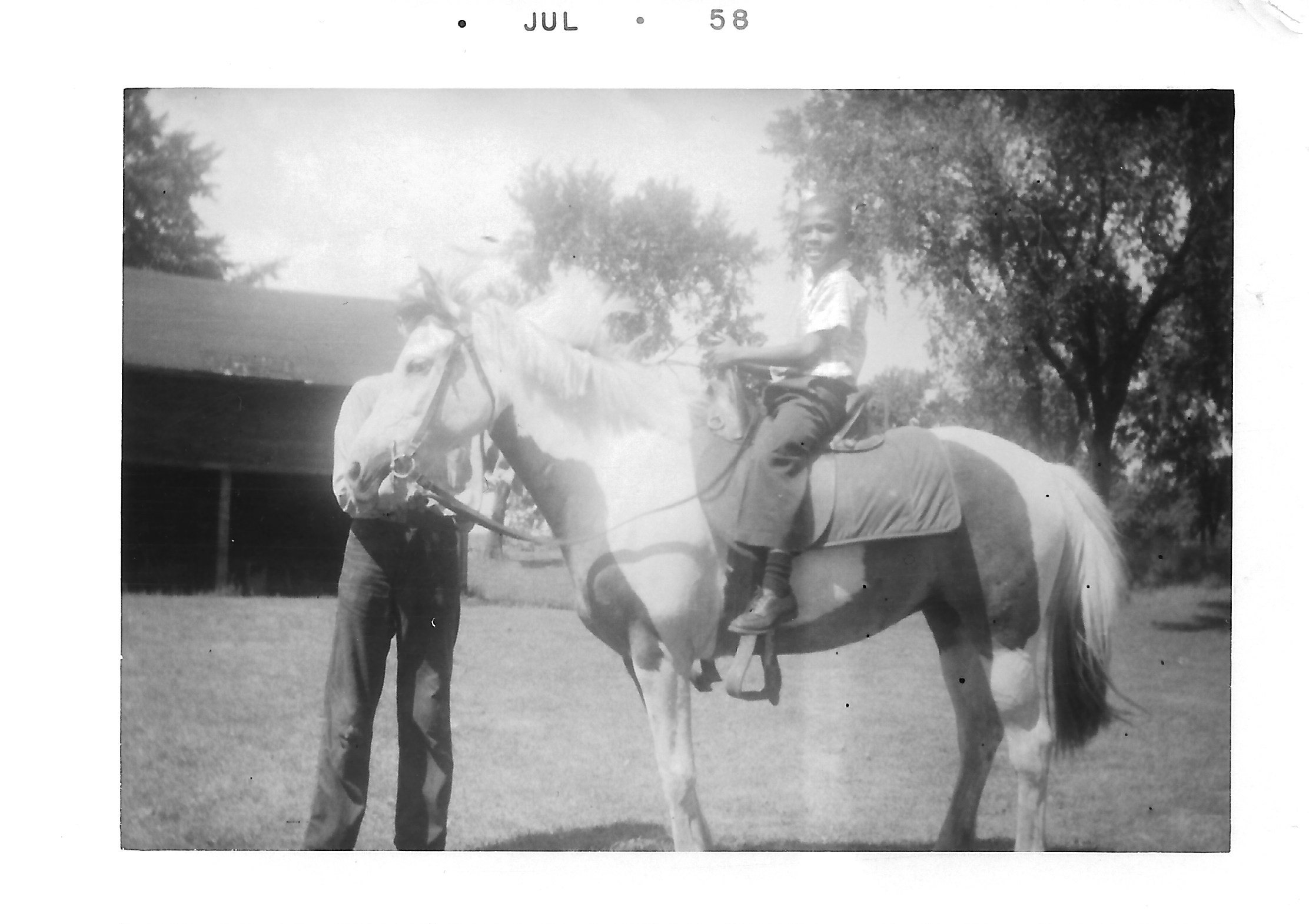

Becoming a Farm Boy

So, my parents had three kids and my mother was pregnant with a fourth, when my grandfather died and we moved out to the farm homestead in Robbinsdale in early 1954, leaving the Phillips neighborhood. The twenty remaining acres of farmland and orchard was beyond my grandmother’s capacity to keep up; and the decision to move our family out to Robbinsdale had economic consequences. My father had been working two full time jobs: one at the Post Office and another at the Minneapolis Park Board. Park Board rules required Minneapolis residency, so he had to give up that job. My parents had to plan to live off one income until the youngest was old enough so that my mother could go back to school for a degree in education and a teaching career outside the home. So, we lived for a few years on the twenty-acre farm homestead with its huge apple orchard, until most of the acres were sold to a suburban tract housing developer. Until then the nearest house was a block away. My father and I did the farm work, harvesting food, primarily for us to eat and for me to sell. Selling apples became my first source of independent income.

Initiation Into the Minnesota Paradox

When we moved out to Robbinsdale, I was quickly initiated into what my colleague Sam Myers calls the Minnesota Paradox. My very first day at Forest Elementary School in Robbinsdale, was a week after the Brown V. Board decision. To figure out what class I should be in, the teacher had me get up and read in front of the class.

As I read, her eyes widened.

She then brought me a higher-level text to read aloud.

Next, she called for someone to take over her class, then shepherded me around the school to read in front of other classes. She told the other teachers and students, “This is what proficient reading looks like.”

I was seven. I understood enough to know that I was doing very well. My little chest was probably a little pushed out. But I was not sophisticated enough to know what would happen next. Because as soon as we were released outdoors for recess, I was surrounded by a throng of white kids chanting in unison various “nigger” cat calls.

However, one of the things my father had presciently done back in the city, was take me to the Eliot Park Neighborhood Settlement House at Chicago and Franklin (now gone) and enroll me in a boxing program. I knew how to use my fists. Surrounding by these epithet-screaming white faces, I got into one fight after another. After the third fight, the playground supervisor sent me to the principal, who called my mother to come and get me. I was the problem. The so-called “Minnesota Paradox” was right in front of me on that first day of school. No matter how much I excelled in the classroom, it didn’t mean a thing outside of it.

My father, who had undergone that same kind of lone Black kid trial-by-fire in Robbinsdale in the 1920s, had a ready-made answer for me: “I can’t protect you and your sister at school. That will be your responsibility. I don’t want to ever hear that you started fights, but if they start with you or your sister, I expect you to fight back. If they are bigger than you, or there are too many, avoid a fight if you can, but if you can’t, leave marks on them to remember them by. Don’t come home crying to me.”

It was a tough lesson to swallow; but it’s what I learned to live by. I was bigger than most of the kids; I was definitely stronger and faster; and I was a decidedly better boxer. So fighting became part of my modus operandi throughout my elementary and junior high school years.

My only relief in that context was that there was one Native American student at my Robbinsdale school — Lyle Iron Moccasin. Lyle was Cheyenne River Lakota, part of the Leonard Iron Moccasin family, with whom my grandparents had a long, close relationship. Our fathers knew each other since Phillips neighborhood days. My grandmother kept the beaded hand-made moccasins that Lyle’s grandmother had given her in a prized place on the living room mantle. Lyle and I were the lone students of color in our school. Lyle was bigger than I was, and just as fast and strong; but he was less inclined to fight. He left Minnesota many years ago, but returned some years back, devoted to addressing Native American issues. He now works for AIOC in the Phillips neighborhood; and we connected once again at a joint African American / Native American summit.

Many years after my Forest Elementary School experience, I learned that School District 281 had put me on a list of promising athletes. They apparently tracked kids from elementary school onward. I was also on the honor role. But at the same time, I was fighting all the way through; and my elementary and junior high years were very isolating psychologically and socially. To compensate, my parents made a concerted effort on weekends to go back into the city to visit Black friends. We also visited Black farm families in some of the small African American enclaves scattered around the metropolitan area.

Still, the move from city to country was in many ways marvelous–especially before we sold most of the land. I had a wonderful rural agricultural experience, working on farms, growing all varieties of apples and selling them, joining Cub Scouts and then Boy Scouts, developing a sense of wildness and love of nature. I hunted and fished all over what is now the northern suburbs of the Twin Cities. I wouldn’t trade away any of those rich memories.

From Farmstead to Segregated Suburban Tract Housing

When I was about ten, my grandmother and father sold the land and orchard, saving only the hilltop homestead and a few surrounding lots, turning the sale proceeds into education trust funds for her grandchildren. With that sale, and the sale of the last remaining nearby working farms, the invasion of suburban working-class tract housing came to Robbinsdale and Crystal.

A lot of the earlier German and Scandinavian farm families had known my grandparents and their children for decades and had very amicable relationships. But with the new suburban tract housing, much of that old pattern changed. We began to have a series of conflicts with the children of the new suburban homeowners, who were living in what had been my grandfather’s pasture for half a century. They vandalized our house, threw rotten eggs and tomatoes on our windows, etc.

Violent Inauguration of Restricted Covenant

This harassment reached an apex one day when I was about eleven. My father was away at work. I was on one side of the house when I heard my mother screaming. Part of the front lawn was on fire. A group of young whites had poured oil into a 30-foot cross that was flaming. Instinctively, I grabbed my father’s 22 automatic rifle, ran outside, telling my mother to go inside, and fired shots overhead. The white folks ran away.

My adolescent response reflected a siege mentality that increasingly displaced my relatively peaceful rural balance. I became intensely preoccupied — much to my mother’s concern — with weaponry of various kinds. I accumulated an arsenal and operated like I was in an undeclared war.

My father had told some of his friends in Minneapolis who were thinking about moving out of the city, to consider buying a house on what had been our family’s Robbinsdale homestead, in what had now become the suburb of Crystal. A few of Pop’s friends came out and tried to buy a house, but were summarily rejected. The contractor had apparently instituted unwritten restrictive covenants. Black buyers were being prohibited from buying houses on my grandparent’s homestead farmland, and we were simultaneously being terrorized by the new suburban white folks who now inhabited my grandfather’s prior pastureland and orchards.

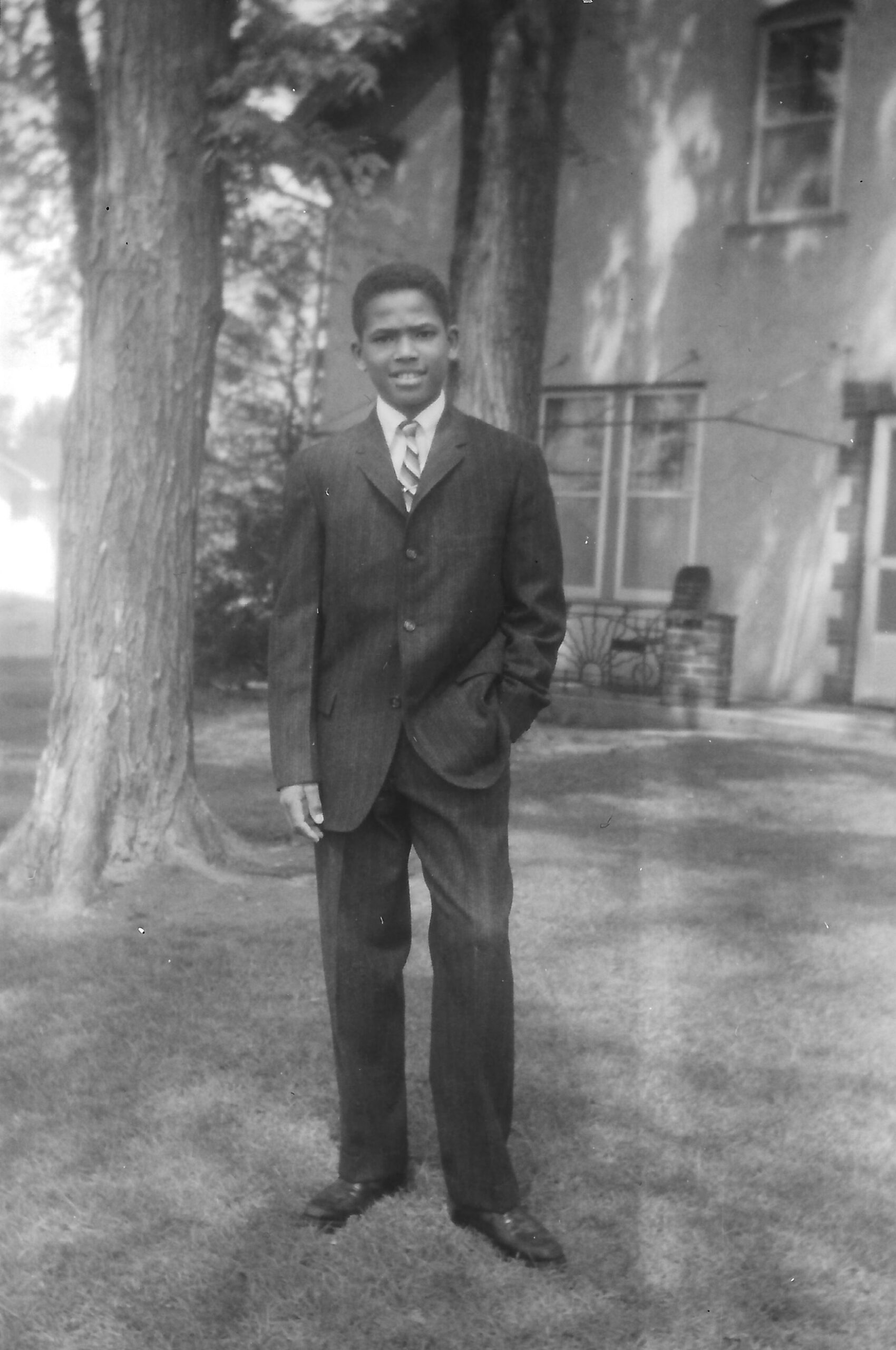

Accelerated High School

Because I had excelled in the classroom, when I finished junior high I became part of an experiment in public education at the time—an “accelerated” group of high-ability students capable of working well above grade level, who were given special opportunities and challenges. I ultimately became a National Merit Scholar. I took university courses in high school, in some cases taught by college professors, and had the opportunity for early graduation, which I took without hesitation.

By the time I reached high school, I was no longer being directly assaulted verbally or physically, as I had been earlier on. I was a lean, highly coordinated athlete, capable of taking most of them out and never failed to do so when necessary. Instead of confrontation, I and my siblings were instead ostracized socially. We were the lone Black students, which was especially hard on my sister Beryl. I confronted a series of incidents having to do with dating white girls, since in the absence of black girls, they were around me in abundance. White females showing an interest in me, and vice-versa, seemed inevitably to end up as a source of strife. Robbinsdale High was at that time the largest high school in the state, with some 3,000 students and almost 800 in my graduating class of 1963—and me the lone black face among them.

Sixteen Years old at University of Minnesota

So in 1963, I graduated from Robbinsdale High School a year early, and in the Fall of ‘63, at the age sixteen, I entered the Institute of Technology at the U of M—and, to my chagrin, the one Black student majoring in electrical engineering. The University of Minnesota in 1963 was a foreboding place for Black students. We could never count more than 75-80 of us, out of 40,000, in any year. There were more students from individual foreign countries than there were U.S. Black students. About half of those few Black students were athletes, recruited from the deep south: Murray Warmath, the Gopher football coach, had broken the Big Ten color bar a few years earlier by signing Sandy Stephens, Carl Eller, Bobby Bell, and company, who brought the University its first national championships. Most Black students were enrolled in General College, a few in CLA. There were no visible Black faculty or staff. It was hard to develop of any sense of community on campus. While Blacks were no longer barred from dormitories as they were when my father was on campus, there were still all kinds of racial problems. The athletic department was exceedingly paternalistic; and coaches from the deep south had Jim Crow attitudes about interracial dating.

Before I got to college however, I had developed a view of my possibilities beyond what the University could offer. My family had broadened my outlook with summer trips to Savannah, Atlanta, Cleveland and Detroit. Whenever John Hope Franklin appeared in the media, my mother would tell stories about him. My Uncle Charles was an ongoing inspiration–teaching law at Howard, and then the University of Illinois and Wayne State; developing U.S. civil rights law at the Supreme Court level itself; working on an international NAACP project to help newly independent African nations like Tanzania establish postcolonial legal systems; mentoring people like John Conyers and Derek Bell—all these expanded my sense of possibility. The March on Washington and MLK’s I Have a Dream speech, happening a few weeks before my first semester began, also gave me a sense of new social and political horizons.

I eventually graduated from the University in 1968, the year Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy were assassinated, in the midst of massive student rebellions. The years in between my freshman and senior years we had the so-called “long hot summers” of massive urban disorders—“riots” the media called them—in which Black folks, in many cases instigated by police brutality, rose up, prompting governors all around the country to call out the National Guard or the U.S. Army to contain them. At the same time, we saw the passage of the national Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and ‘65. These events framed and reframed my social consciousness.

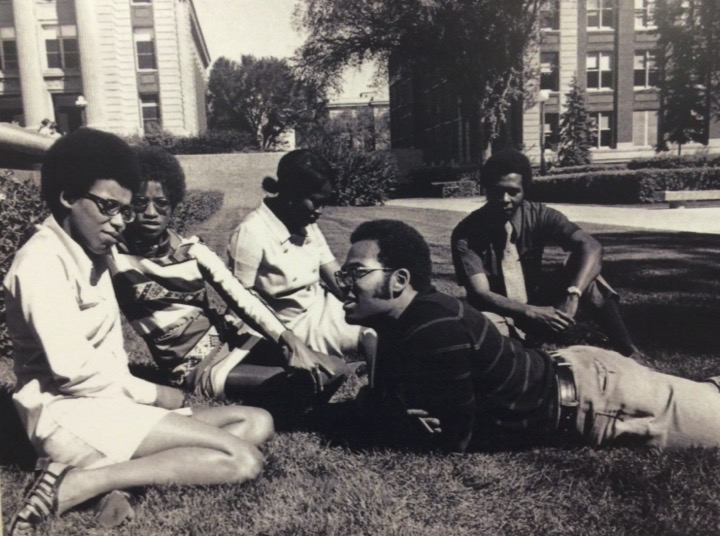

Organizing as Black Students During the Rise of the Black Power Movement

We had established a Black student organization called Students For Racial Progress, STRAP, on campus in 1966. Scottie Stone, from New Orleans, was our group president. We stayed in contact with Black colleges and universities and sent representatives to assist in the Freedom Rides. In 1967, we brought Martin Luther King Jr. to campus. We had him speak on the St. Paul Campus green to an audience of over 4000. He had recently been stoned in Cicero, Illinois and experienced various forms of white violence in other Northern cities. He came to us after spending some harsh weeks living in tenements on the southside of Chicago.

King gave an impassioned address, describing where he had gone politically, psychologically, and spiritually since 1963. He was drafting his last book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community, wrestling with the old civil rights agenda and worldview that he, Ralph Abernathy, and other SCLC leaders had been identified with, an agenda which was increasingly showing its fissures as the civil rights enterprise moved to confront de-facto segregation in the North.

By 1966-67 the Black Power Movement was on the rise. Many of those activists, like Stokely Carmichael, were students of my generation, who started out in the civil rights movement and had been part of SNCC. Our rapidly transforming global perspective was influenced by colonization movements in the Caribbean, Latin America, Africa and Asia. We were reading Franz Fanon and Amil Cabral.

One month after we brought Dr King to campus, we brought Stokely Carmichael, and filled up Williams Arena. He articulated the tenets of Black Power, explaining that he still respected Dr. King as a moral leader, but that morals and ideals do not run the world. Power was the operative issue we had to address. He articulated the position that African Americans had more in common with colonized people in the Third World than with white European immigrant groups in America.

After STRAP brought Carmichael, we decided to change our name to the Afro-American Action Committee (AAAC). In the fall of 1967, Rosemary Freeman and Horace Huntley arrived on campus and quickly became leaders in our new organization. They were both older students from the deep south, Horace from Alabama and Rosemary from Mississippi. Horace had been in the military; and Rosemary had already been involved in civil rights and Black Power organizing in Mississippi. They brought new perspectives and seasoned militancy to our campus organization.

Morrill Hall Takeover

On April 4,1968, when Dr. King was assassinated, we were in a state of shock. A roommate and I were in the old Sergeant Preston’s bar at Seven Corners when the news came on the television. Over that weekend, America went up in flames in more than 100 cities. The U.S. Army was called out to quell massive rebellions. AAAC met that following Monday to decide what we should do that would honor Dr. King and contribute constructively to institutional change. The group asked me to draft a letter of response. I came up with a list of “Seven Demands” for the University, based both on my awareness of what students were doing around the country, and what specifically was needed here. We sent them to President Malcolm Moos. He responded that his administration would form a task force to study the problem.

We made plans for our summer work in connection with those demands. The University had never actively recruited students from local Black, Native American, Hispanic or poor white communities. So, we went door-to-door, passing out admissions information that summer of 1968, while we were waiting for the University to respond to our demands.

Late in the Fall of 1968, we were still eagerly awaiting a substantive response from the University to those seven demands for principled and practical action. they included 200 scholarships for graduating Black Minnesota high school students, an investigation of the policies of the athletic programs toward Black athletes, and a curriculum that reflected the contributions of Black people. The University wasn’t responding substantively; and the task force had made little if any progress. After an infuriating meeting with University administrators two weeks into the new year, we took a vote and decided to act in the spirit of Dr. King’s non-violent civil disobedience, and take over the administration building, which we then proceeded to do on January 14, 1969.

Horace Huntley, Anna Stanley and Rose Freeman were leading us into the building on the ground floor, southern entrance but I told them that we needed instead to go up to the bursar’s office if we were going to stop business at Morrill Hall. That night on the national news, Walter Cronkite announced that Black students had taken over the administration building at the University of Minnesota, attracting the attention of national Black leaders.

After the takeover of Morrill Hall, President Malcolm Moos conceded that the demands that I drafted were “eminently reasonable.” The two major structural outcomes were the creation of the Afro-American & African Studies department, and the Martin Luther King Jr. Counseling and Advising Program. I became involved, extensively, in both of those enterprises.

Inaugurating Black Studies at the University of Minnesota

Though I had graduated with a degree in electrical engineering, my heart was increasing pulled toward African American and African Studies, but there had been no operative program and few courses in any department at the University save History. Happily, the foundations of the AFRO department were formally established in 1969. We brought in faculty from the community, leaders like Josie Johnson and Mahmoud El Kati, a charismatic mentor at the Way Community Center in North Minneapolis, and an intellectual advisor and inspiration for all of us in the AAAC. We fought for a department with tenured faculty, not a program which could easily be disbanded. Lillian Anthony, a Minneapolis civil rights official and a devotee of African culture and history, became the first chair.

Avoiding the Draft by Any Means Necessary

Partly to avoid the ever-present military draft during the Vietnam War era, I had been working in the summers at jobs that prepared me to be a corporate engineer: at Western Electric, Northern States Power, and Pako Photo in Golden Valley. I had been told by my high school advisors, “with an engineering degree you will never have to worry about a job”; and that appeared to be the case, but when I got a good taste of the corporate world, I became disaffected with it. I began contemplating changing my degree in my junior year, but the draft regulations against extending student deferments constrained me.

Earlier, to avoid being drafted into the military as an enlisted “grunt” I had enrolled in the Air Force ROTC program on campus my freshman year, but had quickly discerned that I and military culture were not simpatico, before exiting. During the Vietnam War, all male students faced the prospect of being drafted into the army if we left school or delayed our graduation process without Selective Service approval. The government was now vigorously prosecuting anti-war activists and so-called “draft dodgers”; and I was participating in the anti-war protests. All of us in the AAAC became increasingly opposed to the war, in the same way that we opposed the ongoing colonization of Africa and the Third World.

To avoid going to Vietnam, to serve in a war I could not justify ethically or politically, I had taken a fifth year of college, with the help of an anti-war engineering professor who signed the required papers saying that I needed one more year to finish. Now, as a graduating senior following that year, my chances of being drafted increased. Graduate students were not guaranteed deferment from the draft, but there was some limited consideration from the Selective Service if you were in a graduate program that somehow contributed to the war effort.

I was offered a full fellowship in the UMN MBA program at the Business School, where I became the only Black student in the program. I began taking graduate courses in economics and accounting, and very quickly found I had very little interest in those classes. Moreover, the ethos of business school was off-putting and distasteful to me.

In the Fall of 1969, despite my being enrolled in the graduate program, I was drafted. By then, I had a number of friends who had gone into exile in Canada. Others had defied the draft and gone underground. At that time, many students were doing so and getting away with it because the government could only prosecute a small percentage of those who refused induction. But I had a white roommate who took a public stand against the draft and was prosecuted, convicted and sent to prison.

So I had no illusions that if I openly defied the draft, I would somehow get away with it. Once AAAC became well known on campus, it was seen as a threat by the FBI, who were surveilling Black campus organizations nationwide. Many of us had FBI and CIA files. The draft boards were selectively prosecuting those who would make good public examples. But I was not ready to go to Canada; so I took a subterranean strategy.

I had become more and more involved in weight training and bodybuilding. When I started college, I was underage at sixteen; and women–much to my dismay– were not generally interested in going out with younger men. I took up weight training to look older, and more like my more heavily-muscled football buddies who were BMOCs. Between my sophomore and junior year, I underwent a dramatic physical transformation through intensive powerlifting at a local gym. I came back to campus in the fall with 50 new pounds of muscle. My friends didn’t recognize me. They thought I was a new football recruit, an illusion I did not try to dispel. I was happy to “pass” as a football player.

As it turned out there were a number of guys in the gym who had been in the war, and they counseled me on ways to use the gym training to defeat the military physical exam for the draft. I won’t go into the details here; but on the day I was supposed to be shipped off to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, I got the physicians at the induction center at Washington and 3rd Ave., to send me out to the VA hospital for special cardiology and neurological tests where I was ultimately declared physically unsuitable for service—though, the examining neurologist said, “You look very healthy.”

Leaving Business and Engineering for Literature and American Studies

After eluding the draft, and reexaminIng my goals in life and education, I resigned my research engineer job at Pako Photo, gave back my MBA fellowship funds, and looked for alternatives that better suited my enthusiasms for history, humanities and Black Studies. I had spent my extra year of college taking history, philosophy, political science, anthropology and literature courses. My classes in the English Department were pivotal, especially courses by Toni McNaron, who later helped form the Women’s Studies Department, and Chester Anderson, an expert in Irish and Black literature.

My experience in their courses inspired me to sign up for a Masters in English and American Literature. Because my undergraduate degree was in the sciences, not the humanities, I was only allowed in provisionally, but that was all I needed. I had been a very good writer from very early on and an extensive reader. In high school I was reading Dostoyevsky, winning statewide essay contests, and excelling in debate. I was no stranger to the arts and humanities.

I ended up developing close relationships with some of my English professors, including Samuel Holt Monk, world-renowned scholar on 18th century English literature, who had once summoned me to his office to talk about a paper he said was so brilliant that he wondered if I might have consulted some sources I failed to cite. But I brought along my midterm blue book to that meeting, in which he had given me an A+ and extended written commentary. After our meeting, Professor Monk encouraged me to take more courses with him, and to consider specializing in 18th century English Lit. He and several other professors would ultimately declare me the best expository prose stylist in the English department graduate program.

Unreconstructed University of Minnesota

But the English Department was, nevertheless, unreconstructed. With the sole exception of Chet Anderson’s course on Black writers, we read no African American authors, there were no professors of color, and there were no other Black graduate students in the program. So when I finished my English master’s degree, I signed up instead for a Ph.D. in American Studies, which was also unreconstructed but, fortunately, was multidisciplinary. We took courses in Anthropology, Sociology, Music History, Religion, Philosophy and Political Science, which allowed me access to people like Mulford Q. Sibley.

Most exciting, it allowed me to take advantage of a new graduate program within the History Department called the History of African Peoples. It was one of the first graduate level programs in the country that focused on comparative history in the African diaspora. Faculty included Lansine Kaba, Russell Hamilton, Russ Menard, Alan Spear, Stuart Schwartz, Alan Isaacman and August Nimtz. Best of all, they brought in a cadre of ten to twelve Black graduate students — many of whom would become leading lights in African American Studies: people like Earl Lewis, Joe Trotter, Quintard Taylor, and David Taylor. It was an exhilarating experience for me—and a stride forward out of intellectual isolation into camaraderie. Being allowed to design a customized hybrid Ph.D. program that fused he History of African Peoples with American Studies was an exhilarating experience for me and a stride forward out of intellectual isolation into inspiring camaraderie.

MLK Program Counselor

However, I had had no fellowship support in English or in American Studies; and there was no financial support for us in the History of African Peoples Program either. All of us had to fund ourselves. I worked as a CLA Advisor first counseling students who had applied to the Institute of Technology and been rejected and who were trying to get their grade point averages up to reapply. Eventually I was reassigned as a counselor in the new MLK Program (one of the institutionalized outcomes of the Morrill Hall takeover). The first MLK director was a very dedicated white woman named Barbara Uppgren. But by the second year, I took over as Director, running the program from 1971-1973. We had a superb staff of traditional academic advisors and counseling psychologists who helped non-traditional students of color, as well students coming to the University through social welfare programs, prison convict release and veterans’ programs. I developed a strong interest in and knowledge of counseling methodologies and educational psychology. One of those staff people was Harriet Haynes who later became head of Student Counseling at the U. For a while I, very fortunately, lived with Black graduate students who were in the Clinical Psych and Ed Psych graduate programs.

Building Bricks Out of Straw: Black Studies at Carleton College

When I finally finished my Ph.D. coursework and prelims in 1973, Lansine Kaba and Russell Hamilton recommended me for a position at Carleton College, where Black students had pushed the administration to build a Black Studies major. Upon relocating to small town Northfield, Minnesota, I and art professor George Jones apparently became the first regular Black faculty members at Carleton. I took the appointment with my dissertation unfinished and no idea how demanding the job would be to create a program from the ground up—circumstances that were recurring across the country then. In many cases, colleges were asking junior black faculty like me to perform the academic equivalent of building bricks out of straw. Little financial or staff support was being provided for the Black faculty being recruited; and I was given no paid release time for my administrative labors.

Paul Wellstone had joined the Carleton faculty a few years earlier as the lone Jewish professor and a political radical in a very conservative political science department. His mission was to create a Chicago-based Urban Studies program at Carleton; and he had ties to Jesse Jackson’s PUSH organization there. Paul and I collaborated in building both programs.

I spent ten years at Carleton. It was a challenging professional and personal learning experience on multiple levels. My sense of intellectual and social isolation was profound, though I had some wonderful colleagues. I was living in Northfield, a single, Black male, tenure-track professor on the Carleton campus. That was social strain of the first order. Looking for professional and social supports, I strenuously applied for and received national grants for research trips—and escapes—to the Harlem Renaissance archives at Atlanta University, Howard University’s Moorland Spingarn Collection, the Amistad Collection in New Orleans, the Schomburg Research Center in Harlem, and the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute at Harvard, researching and building networks for myself.

Directing African American & African Studies at U of M

In 1983, Lansine Kaba and Russell Hamilton asked me to come back to the University of Minnesota to teach in African American & African Studies; and I was ready to put Carleton in my rear view mirror. So I came back in the Fall of 1984 with the specific proviso that I would not have to chair or take on other administrative duties and that I would have full support in completing multiple research and publication projects that I had been postponing for a fifteen years while being cornered and cajoled into administrative duties, first at the U of M and then at Carleton. Five weeks into the semester, however, and much to my dismay, Lansine Kaba resigned from the University, and I was implored to take his place as chair. Cornered by the Dean, and without many expedient options, I agreed to do so. I ended up chairing the department productively for the next eight years.

Developing the Archie Givens Sr. Collection at the U of M

Once I settled in and reconciled myself to my administrative fate, I began focusing on how we could build African American archival resources for students and faculty at the U. I was teaching courses in African American literature and had a pretty devoted group of Black students. They included a bright, energetic young black woman named Amy Russell, who I helped get an internship in the rare books collection in Wilson Library. One day I got a call from Amy, saying, “Professor Wright, you need to come over here. A catalog for a private collection of Black literature has come in, and they’re about to put it away on the shelf.”

A white, New York, Brooklyn-based playwright and community college teacher named Richard Lee Hoffman had spent the previous quarter century collecting African American first edition literary classics, ephemera, pamphlets, and playbills linked to the Harlem Renaissance. He didn’t want to break up his collection or sell it piecemeal, so he had an agent send around the catalog to major universities around the country. There were over 3000 items in that catalog, and with it a chance for the University of Minnesota, in one dynamic step, to acquire a collection of national quality.

I went to the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, Fred Lukermann, and told him, “We’ve got a rare opportunity that we can’t afford to miss.” The collection was priced at $125,000, a fraction of its market value. Fred and I spoke to U of M President, Ken Keller, to ask for his support. Presidents in those days had sizable discretionary funds. Ken agreed to provide a loan that would have to be repaid to the President’s office; and the terms we secured with Hoffman’s agent for purchasing the collection gave us 60 days to raise the money.

Typically, the way collections are acquired at the University is that they have some kind of standing advocacy group made up of faculty, students, the larger community, etc. Nothing of that sort existed for African American literature, so we had to build the enterprise from the ground up. I contacted friends, associates and alums at the University: Claudia Wallace Gardner, Leroy Gardner, and Ezell Jones — a very active former Gopher football player and dedicated alum—to begin a fundraising campaign and mobilize the local African American business community. To help energize this organizing group, we contacted the Givens family, who already had an educational foundation linked to Minneapolis K12 schools. Archie Givens Sr. had been a strong advocate of public education. The Givens family agreed to refocus their foundation to prioritize the University and to focus on higher level community outreach. We were able to recruit a dozen Black families willing to contribute $10,000 each, alongside the Givens family contribution of $75,000. That was how we raised the money to repay the University and have a little surplus.

Building what we initially called the Black Literature Collection but later renamed as the Archie Givens, Sr. Collection became my focus for the next decade. There were no curators on staff who were familiar with African American literature, culture and history, so I became the ex-officio curator and faculty scholar, pro-bono, with no release from my classroom or administrative obligations. We began with the operational commitment from the outset that this would not be one of those collections that sat in the archives and was visited only by professional scholars. This would be a living collection, part of a communiversity — a term that we borrowed from Mahmoud El Kati, the legendary scholar and community activist who has been a powerful continuing influence on me and so many others.

Ken Keller forgave that initial loan, and we put that money to excellent programmatic use. We mounted training projects with teachers in the Minneapolis and Saint Paul school systems, junior colleges and elsewhere. I also became a member of the Minnesota Humanities Commission, which hosted a number of teacher training projects. Through the University’s summer extension division, we brought in teachers to develop innovative new curricula to implement in their schools. We created an online website so the curriculum could be shared. That was an energizing program. We got artists, activists, poets and writers in the community involved.

Rekindling Memory and Interest in the Harlem Renaissance

These days people might not understand that the Harlem Renaissance had essentially disappeared from public perception after the 1940s. The only place it survived was at historically black colleges and universities, because significant numbers of the key figures in the Renaissance continued to teach in those institutions during the 1940s and 50s, when higher education was still racially segregated all across the country. I had met Sterling Brown at Howard University in the 1970s; the legendary scholar-poet who mounted the first national conference on the Renaissance after his colleague Alain Locke died in 1954, a conference which Sterling called The New Negro, Thirty Years Afterward.

Sterling used the geographically broader term, “New Negro Movement.” for the 1920s-1930s explosion of African American culture. “Harlem Renaissance” was a localized scholar’s term, first used by the legendary poet Melvin Tolson in his master’s thesis at Columbia University in the 1930s. John Hope Franklin had then used it in his classic history From Slavery to Freedom in the late 40s. Still, if you went to research libraries outside of HBCUs, as late as 1970, you would not find a reference to the Harlem Renaissance. It remained invisible and as a consequence, there had been no public exhibitions on the period.

Mounting a Traveling Exhibit on the Harlem Renaissance

So I contacted Colleen Sheehy, Assistant Director of the Weisman Museum. We co-wrote a NEH proposal to create the first national traveling exhibit on the Harlem Renaissance. We won a grant for $250,000 and brought together a distinguished national board of advisors, including my sister Beryl, who had become part of a group of Yale University Black art historians. We created the exhibit, “A Stronger Soul Within a Finer Frame: Portraying African Americans in the Harlem Renaissance.” It toured the country for three years, 1990-1993, and was seen by more than a million people at HCBU’s, Black community centers, and settlement houses, as well traditional museums and exhibition spaces. It was enormously successful. After that three-year run, it got new life and additional funding support from local foundations to tour around the state of Minnesota.

Through the exhibit, we helped the word get out nationally about the 1920s & 30s Black community arts phenomenon. We began to get offers of materials related to the Renaissance from all over the country. I spent significant time and energy reviewing and collecting, purchasing, or acquiring by whatever means necessary, materials that became part of the collection.

The Langston Hughes Manuscript

Langston Hughes and Zora Neal Hurston were the pivotal figures that we used as guiding lights for the exhibition. In midlife, Langston wrote screenplays, novels, and historical works. Later in his life, in the 1950s, he returned to what he considered his primary work—poetry—writing a series of volumes, one of which was called Montage of a Dream Deferred, which, unlike some of the earlier more folkloric-styled and blues-based poems, showed the influence of American modernism. He dedicated it his close friend and mentee, Ralph Ellison, and Ralph’s wife Fannie Ellison, whom I had met when I helped orchestrate the first scholarly conference on Ralph’s work at Brown University in 1979.

Following Dream Deferred, Langston re-immersed himself in jazz and blues as an accompaniment to performance poetry. He was one of the precursors to the Beat Generation, and later, hip-hop. He lived to see and influence the emergence of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 70s.

In 1960, Langston Hughes served as the emcee of the Newport Jazz Festival, which coincided with a pivotal year for global freedom and anti-colonial struggles in Africa, the Caribbean, and the U.S. civil rights movement. At the Newport Festival, promoters were swamped with public appeals for tickets; but ultimately they had to turn away a large crowd who “rioted” for several days in that elite Rhode Island community. The National Guard had to be called out to quell the “jazz-crazed” crowds, and the festival was closed down. Langston had to reside over the final session.

Langston had a vision there for a multidimensional artistic project that would become his praise poem to the freedom struggle globally, and that would use jazz and the blues and other forms of African diasporic music as its framing motifs. He began writing what would result in a suite of jazz poems that he called Ask Your Mama: Twelve Moods for Jazz, inspired by the vernacular verbal street dueling provocation: “ask your mama…”

Langston wanted to perform the new suite with musical accompaniment, before a live audience; and he had earlier put together a thematic cluster of a poems and performed them with the great jazz bassist and composer Charlie Mingus. He proposed to Mingus that they perform Ask Your Mama, but Mingus health prohibited that, and then Langston died in 1967, before he could realize this performance dream.

By a marvelous turn of good fortune, we had acquired from one of Langston Hughes’ Dutch collaborators, a complete typed manuscript that included his musical liner notes for Ask Your Mama.

Performing Langston Hughes’ Ask Your Mama: Twelve Moods For Jazz

So, I said, why don’t we do it ourselves. The head of the jazz studies program at the University of Minnesota since the 1970s had been my colleague and dear friend Reginald Buckner, a consummate musician, dedicated teacher and one of the most sweet-souled human beings you will ever encounter. Reggie had been battling the U of M music schools over the status of jazz in its hidebound conservatory-based musical program steeped in the exclusionary European classical tradition. The battle had driven Reggie nearly mad, and ultimately to premature death.

As part of the efforts to celebrate Reggie, I brought together with one of Reggie’s collaborators, Frank Wharton, a local Black musician-teacher, and Sowah Mensah, a Ghanaian percussionist, and said “Lets perform a couple of the Moods from Langston’s Ask your Mama suite at the School of Music memorial for Reggie Buckner.” So, we did.

Then, for the grand opening of the newly completed Weisman Museum, Colleen Sheehy asked us to perform the entire Twelve Moods. With members of Reggie Buckner’s faculty jazz quartet, we created a multimedia performance. To accompany the poetry and music, I constructed a duel set of synchronized photographic and art slides, thereby adding a visual component. The performance got rave revues and we got calls to perform it at other venues. The Walker Art Center was preparing to host a traveling exhibition on the Beat Movement, and they wanted to include the African American dimension. So we did a performance double-billed with Amiri Baraka, on the Walker stage.

From there my Langston Hughes Project project continued to spread. I was still chair of the Department, and curator of the Givens collection, still trying to do my own research. But it was a heady time. We toured the country for a decade, performing in dozens of universities and concert halls, inspiring others to perform it — but nobody else had developed the three dimensions–verbal, musical and visual. Eventually the technology of the slides advanced and became digital. One of my very important collaborators was E. G. Bailey, local Liberian American multi-media artist, filmmaker and playwright. He became my regular videographer for the Langston Hughes project.

Ultimately, I performed at Carnegie Hall with the Carnegie Hall jazz band playing in its final season, during the fall of 2000. As the spoken word artist, this time I was double-billed alongside a slate of ballet dancers, opera singers, and the famous cabaret singer Bobby Short. We got a rave review in the New York Times. They called it an “unlikely performance with an unlikely star, the scholar and academic, John S. Wright.”

Film Documentarian

At the turn of this new millennium, my teacher training projects and the summer Harlem Renaissance seminars also reached an endpoint, in part because the U’s summer term programs for teachers were shrinking. At the same time, funding for K-12 school systems were eroding. These were not good developments, but for me, it was a good time to change my focus.

I began teaching courses on African American cinema and became involved with creating documentary films on African American history. Dan Bergin, someone I mentored, had become a leading producer for TPT. We began doing documentaries on Black Minnesota and regional African American history, including a series called North Star . I also became involved with consulting for national documentaries, some done by PBS, some by independent black documentary production enterprises. Blackside Productions was one of them, linked to Henry Hampton, who created the Eyes on the Prize series. I served on the consulting board for the WGBH series Africans in America, for which one of the producers was Llewellyn Smith, a former Afro-American Studies major of mine from Carleton.

I also consulted for a documentary on the early Black filmmaker, Oscar Micheaux, and a PBS series on African American modern dance. Last spring, on TPT, we released a documentary called This Free North: Black History at the University of Minnesota, which drew on campus research linked to the Morrill Hall Takeover and materials tracking back into the nineteenth century. Documentary filmmaking became a new way for me to make contact with broader audiences and create visual teaching tools for the African American educational world.

Mentors

My life was increasingly being influenced by my contacts with generations of former African American graduate and undergraduate students of mine, whom I had helped move into professional worlds where they were now calling the shots. At the same time, Mahmoud El Kati continued to be a mentor for me, reminding me of my commitment to public education and the communiversity idea. Mahmoud is still creating these educational enclaves of younger Black folk that he pulls me into, very willingly. For a while we met at the Golden Thyme Coffee House to screen films and hold discussions with young activists. Now he’s shepherding an enterprise called New Skool.

Pan African Perspective, Global Travel

At the same time, connecting with the African diaspora globally has been important to my research since graduate school days. I traveled to Haiti in 1979 with Atlanta U professor Richard Long’s New World Festival of the African Diaspora. That was during the later years of the Duvalier regime. We were a group of African American scholars and artists, there to study Haitian and Haitian American history and culture, invited by the Haitian American Institute. It was a powerful experience. After that, every other year the New World Festival would travel to a different part of the Black world. One of the most noteworthy junkets for me took place in 1988 when we went to Brazil during the centenary of that nation’s abolition of slavery; and we participated in the celebrations in Salvador de Bahia, the heart of Black Brazil.

In 1991, I got a Fulbright Fellowship to travel to Ethiopia and the University of Addis Ababa as a visiting scholar, invited by Ethiopian faculty and students who had seen the title of my two volume, 500 page, Ph.D. dissertation: “Ethiopia in Babylon: Antebellum American Romanticism and the Emergence of Black Literary Nationalism.” They wanted me to lecture about Ethiopianism.

I went to Ethiopia when things were politically precarious. A Marxist revolution had taken place and the various secessionist movements exposed the divides between the traditional Amhara elite and the Tigrayan, Eritrean and Oromo subgroups.

On another occasion, I traveled to Ghana with students of color from a non-traditional alternative arts high school in St. Paul, funded by one of the local musical associates of Prince, a rapper named TC, who had a strong interest in promoting arts education. Most of those students had never been out of the state, let alone out of the country; and none of them had ever been to the African continent. We took about twenty students. At the University of Ghana in Accra, I gave a talk about an 18th century Ghanaian theologian, and then we toured slave coast castles, most notably the Elmina Castle. It was a transformative experience for those students and a rich one for me, being around those young folks on African turf that I had long researched but was visiting for the first time.

The Diasporic Spread and Significance of African Games

As a spinoff of my dissertation research on 19th century African American literary and cultural history, I had devoted considerable time at Harvard’s W.E.B. Du Bois Institute, studying the pages of the first US Black literary periodical called The Anglo African Magazine, published in New York City in the late 1850s by pioneering Black New York journalists, scholars and activists. It presents a fascinating angle of vision into the inner life and outer activities of Black folks on the eve of the Civil War.

In that volume was an unsigned essay simply titled Chess, an utterly astounding capsule exploration of the intellectual and psychological faculties that went into making a consummate chess player. It was written in the context of the First American Chess Congress, which took place in 1857 when chess was just being established as an organized international phenomenon. At the Congress, the final match was between an exiled German chess master named Louis Paulsen and a young New Orleans Creole named Paul Morphy—the 19th century equivalent, and idol of the 20th century’s Bobby Fischer. Like Fischer, Morphy was a child chess prodigy who had become the greatest player in the world. The anonymous essay made it clear that Morphy’s ambiguous racial identity had special interest for a group of Black and Jewish chess players who met regularly back then, and that the author of the essay was analyzing them, and their playing styles and political lives as well.

I began probing and eventually discovered that the author was the first university-trained African American physician, James McCune Smith, the mixed-race offspring of a self-emancipated black bondswoman and a white father he never knew. Smith had gone to the New York African Free school which was supported by Quakers, and the African Methodist Episcopal Church. They also supported his medical education abroad in Scotland and France, when no American Medical schools would admit Black students. Smith returned to New York to start a medical practice and dedicate himself to the struggle to abolish slavery and gain first-class citizenship for free Black people. He was one of the most highly educated Americans of any sort at that time, fluent in five languages including Latin, Greek, German and French; and he was the primary intellectual mentor of none other than Frederick Douglass, yet Smith remains largely unknown even day.

This spurred me on what would become a scholarly research obsession: the history of chess, the interconnected study of ancient Egypt, the rise of Egyptology, and the history of abstract strategy games in the African world, including the mancala family of games transported to the New World during the Atlantic slave trade, over the course of five centuries. From 2012 on, my wife Serena and I have traveled to South Africa, Kenya, Cuba, Antigua, Jamaica, Barbados, and elsewhere, tracking the links that tie these abstract strategy game traditions to political, cultural and psychological history, all in the context of the struggle for freedom.

A Campus Divided

I retired from the University two years ago in 2019. During the previous years, I served as an advisor for a pioneering campus exhibition called A Campus Divided: Racism and anti-Semitism at the University of Minnesota, 1930 to 1950, put together by Professor Emeritus Riv Ellen Prell. With an enormous dedication of time, energy and personal resources, she and her graduate students turned up new troves of information about the underbelly of the University’s institutional history. I had done some work on this earlier, for Twin Cities Public Television projects and articles in the U Alumni Magazine in connection with AAAC reunions held at the 37th and 40th anniversaries of our Morrill Hall Takeover.

The Campus Divided exhibit went viral, and brought intense scrutiny to the University. New groups of students on campus who were grappling with current issues of exclusion, discrimination and marginalization, became increasingly energized and mobilized. In 2019, the intertwined histories of American higher education and American slavery had become a national issue, alongside battles over Confederate monuments and rightwing extremism, affecting universities across the country. At the U of M, this became manifest in the call to rename those buildings named after culpable University administrators, Coffman and Nicholson, especially.

President Kaler established a task force to consider renaming buildings on campus; and I participated as a member of the initial task force, offering my insights, my background, research, and family history as context.

Board of Regents Meeting, April 2019

Ultimately this would lead to a confrontation at the Board of Regents meeting on April 28, 2019, in which the Board was supposed to vote on the recommendations to rename the buildings. The room was filled with students and faculty. But It was not clear that anyone other than a Regent, was going to be allowed to speak. Regents protect their meetings fiercely; and they have total control—officially.

Professor’s Riv Ellen Prell and Elaine May were up in front of the throng of protesters. The police had surrounded the chamber. The proceedings were being shown on camera outside to a large crowd in the hallway. Calls went up to have me speak. When I initially stood up, a Regent threatened to have the police remove me if I didn’t sit down. Ultimately, President Kaler intervened and advised, “Let him speak.”

The Regents did not know who I was, my family history, my role at the University, or that this was not the first time the administration threatened me with arrest. They allotted me ten minutes. I think I spoke close to 20, framing the moment in a larger historical context, going back to my grandfather’s era and experiences with the University more than a century earlier. This all took place a few days before a retirement party for me on the West Bank that my wife masterfully orchestrated. My address to Regents went viral and ended up drawing some commentary in the New York Times.

The Murder of George Floyd

Regarding the George Floyd murder and all it has come to signify: it is impossible not to pay attention to it at this juncture. A number of my former students are members of local Black Lives Matter, playing leadership roles. I’m proud of them for their engagement and staying power. I’ve tried to pass on the need to develop a genuine historical consciousness in which you understand that the struggle for freedom is transgenerational. It is ongoing and unceasing. You have to be able to think in those terms and at least have some grasp of what has transpired historically, in order to know what not to do as well as what to do; what’s possible and what may not be possible; the difference between the contexts of the past and the contexts of the present.

A Personal History of Police Abuse

I’m retired now but I’m still a citizen, still engaged in educational enterprises, and trying to complete long gestating writing and research projects. And I have personal connections to what happened to George Floyd at 38th & Chicago. The first house I bought as an adult was on 39th and Fifth Avenue, just a few blocks away in that southside neighborhood. It is impossible for me to forget that since age fifteen, when I first acquired a driver’s license, I was being stopped for “driving while Black.” When I left or came home then, from the Robbinsdale homestead, police assumed that I wasn’t where I was supposed to be. Later, as a student member of the AAAC, we were being surveilled and harassed by Minneapolis and University police, and by the FBI.

More pointedly I had an indelible encounter with brutal security guards and Minneapolis police officers back in 1971, in the old downtown Minneapolis Dayton’s building. I was unjustifiably suspected of shoplifting, though I had in my hands the box with the sales receipts for the special order merchandise I had purchased. But I was nevertheless confronted at gunpoint, forced onto the ground prone, handcuffed behind my back, and detained behind closed doors by security guards and Minneapolis police. It was an enraging near-death experience that left me with recurring nightmares for more than a decade. After seeing Darnella Frazier’s video of George Floyd’s murder in 2020, that horrendous fifty-year-old scenario was retriggered in my long submerged subconscious memories.

Precarious Justice