I had learned to navigate the world at that crossroads of misogyny and racism. Now I stepped out as a Black man and my whole world turned upside down. I experienced overt violence. It was the first time I had negative interactions with the police. I did not understand the Black experience of racism until I literally experienced both sides of it—or I should say all sides, because there is no real binary.

— Phillipe Cunningham

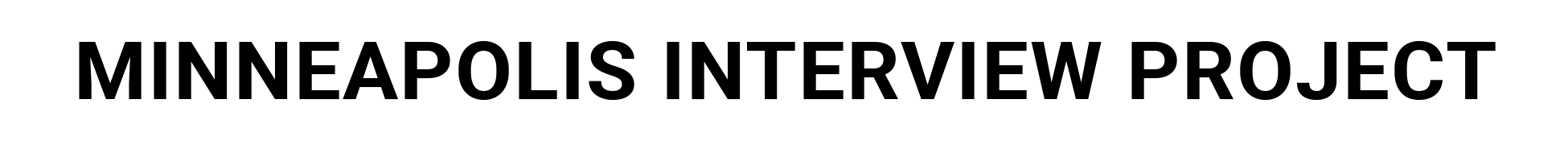

Being “First” and “Only” as a Black Kid in Rural Illinois

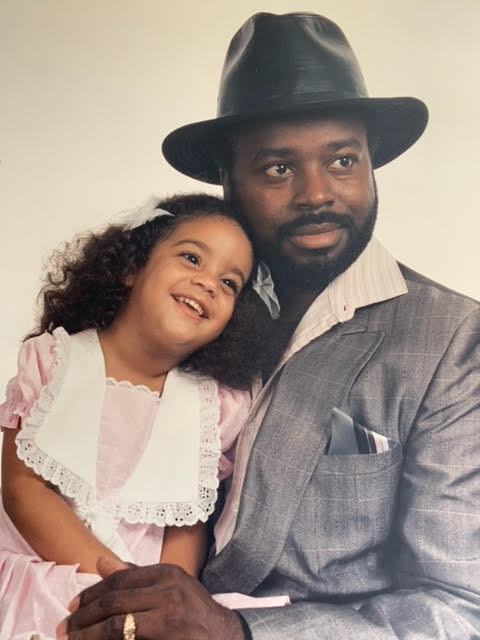

We were one of a handful of inter-racial families in Streator, Illinois, a rural town 100 miles from Chicago. I was the only Black kid in my class, the first Black kid to be elected to student council in junior high, the first Black kid to be student class president (three years in a row), the first Black kid to be a have a high-ranking elected position in Key Club International (a youth Kiwanis Club) in Illinois and half of Iowa.

In Oakland, Where Black is Beautiful

As a youth, I counted down the days to when I would be old enough to leave home.

A few weeks after I turned 18, I ran off to college to southern Illinois. If I had known about them, I would probably have gone to a HBCU, but I didn’t have HCBU awareness. I thought, where are there a lot of Black People? Oakland! Home of the Black Panthers!

At my first opportunity I moved to the Bay Area. I took one summer session at Berkeley and then transferred to Mills, a women’s college in Oakland. It was a good place for me. For the first time in my life, I was surrounded by “Black is Beautiful.”

I moved to the Bay Area in 2006. Remember what happened in 2008? The Great Recession.

The college lost endowments and I lost tuition assistance. I ended up leaving college and working full time as a youth worker. I was a dancer, classically trained in ballet and tap, but my preferred styles were modern and jazz, and I had performed in Chicago and the Bay Area. I also had a background in martial arts and gymnastics. I figured I could teach kids to dance.

Teaching Special Education on Chicago’s Southside

Turned out I was really good at working with youth, and I loved it. I decided to go back to college and become a teacher. I moved back home and enrolled at De Paul University, completing both the undergrad degree in Chinese I had started in California, and a post-baccalaureate program in special education. With those credentials I was able to land a job as a Special Ed teacher on the south side of Chicago.

My classroom was thirteen high school kids, each of whom needed a one-on-one para- professional, but I only had two. In addition to having the fewest resources and the neediest kids, the school was a toxic work environment. There was a very nasty division between white and Black teachers. By that time, I had transitioned, but I was stealth trans person, which means you just don’t tell people that you are trans. As far as my coworkers knew, I was a Black gay guy, someone who didn’t perform black masculinity in a way that aligned, which caused a lot of threats to my safety.

Coming Out and Transitioning

For those of us who are both transgender and queer coming out to yourself and the world is like peeling an onion. Am I like this? No that’s not me. Who am I? I grew up without representations of Black queer trans people. When I was 22 years old, I took a LGBTQ American Studies to a multicultural requirement at De Paul University. I read a story about a gay transgender man. I sat back and went, “Oh my God, finally!” Two weeks later I was out to the world. Once that light bulb went on, I couldn’t turn it off.

Coming out was not dramatic in my immediate circle. My mom had a hard time at first, but she eventually got over it. My dad was like, “Ok, cool.” The people around me knew I was going to do what I wanted anyway. I’m a headstrong kind of person. The drama I experienced was in the broader world.

The hardest part of my transition was navigating in the world as a Black man. I had learned how to survive as a Black woman. I was a femme woman. People wouldn’t look at me and say, “Yeah that women is on her way to becoming a dude.” I wore makeup, I wore jewelry. I had learned to navigate the world at that crossroads of misogyny and racism. Now I stepped out as a Black man and my whole world turned upside down. I experienced overt violence. It was the first time I had negative interactions with the police. I did not understand the Black experience of racism until I literally experienced both sides of it—or I should say all sides, because there is no real binary. Once I made my medical transition and had masculinized to the point where people on the street saw me as a man, I became public enemy number one.

I am a small person. Folks were pushing me on the sidewalk, cutting in front of me in line — those kinds of interactions. And I was experiencing horrible racism from gay men. The anti-blackness did not just come from white gay men, but also from other non-Black gay men. And, trust me, they were transphobic too.

I came out in 2010. I know that is not forever ago, but in terms of transgender rights, it is. There weren’t a lot of trans men in the public eye, eleven years ago. I was navigating spaces as the only trans man and living an entirely new Black experience. I experienced multiple levels of marginalization; different forms of racism, homophobia, and transphobia, all in my first 25 years. Although living it was traumatizing, now, as a professional and a policy maker I see these experiences as an asset.

But I certainly didn’t see them as an asset at first. I was just surviving. It wasn’t until I moved to Minneapolis in 2013 that I had this moment, of “Oh, my experience is valuable!” Everything I have survived, means something. But it took time.

Teaching in Chicago during the 2012 Teachers’ Strike

I loved my students. I still have my class picture up in my office. I would have been a teacher for the rest of my career if the circumstances would have been better. I was 23, working as an autism specialist. The students had high needs and they weren’t getting the supports they needed. I was not either.

And then the 2012 Chicago Teacher’s Union strike happened. That was my first real awaking around the power of local government. In Chicago the mayor has control of the school district and appoints the superintendent and the school board. During my time there the superintendent was arrested, charged and later convicted of fraud. The education system in Chicago was a mess from the top tier all the way down to the classroom.

As a teacher I saw sweeping policies being made without regard to their impact on kids living on the south side. I had this clear moment in which It thought, if there was a teacher in the mayor’s office, most of this drama could have been avoided. As it was, Rahm Emanuel closed 54 Black and Brown schools. That was my final straw. I could not work in a district where the higher-ups don’t care about Black and Brown kids and I couldn’t live in a city that treats kids as if they were disposable. I was not only ready to leave my job; I was ready to leave Chicago.

Getting to Minneapolis

I wrote on Facebook that I was looking for a city to move to, thinking about Oakland or Portland, thinking I needed to get out of the Midwest. A Chicago friend of mine responded, saying I should think about Minneapolis, a place where she had lived, and felt safer as a Black queer woman. I had been feeling really unsafe in Chicago as a Black queer man. That meant something to me. The stars aligned. I was working at a hotel in Chicago, and I got a job transfer to their Minneapolis establishment. I also applied and got into the School of Public Health at the University of Minnesota. I hopped a Greyhound bus from Chicago and landed in Minneapolis. Best decision of my life.

I had one acquaintance in the city, who put me up for a month, until I found an apartment. I asked, “Where do all the Black folks live in this city?” That is how I ended up in North Minneapolis, in the 4th ward, where the Black people were, and the only place I could afford an apartment.

Youth Work: Non-profit and Policy Fellowships

I decided not to go to grad school in public health. It was going to be really expensive, and I already had a lot of student debt. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do, but I knew I wanted to work with youth, on the policy side, advocating for programs that actually help, and don’t hurt kids. I looked for a job in a non-profit. I found a fellowship with the New Sector Alliance, for people who want to go into non-profit leadership. I was the first one selected in the first cohort in the Twin Cities. I told them I wanted to change the system rather than do direct youth service. They said, “Great, we have other options.” But guess what I chose? Direct service with youth. I just could not help myself. I really love working with kids.

I got a position at the Wilder Foundation with their Youth Leadership Initiative working primarily with Hmong and Oromo youth, teaching them about policy, and political organizing. I took them to the Capitol where they testified in front of a legislative committee. It was really cool work.

While I was there the Wilder Foundation started a new policy initiative called the Community Equity Pipeline. I become involved in that and was part their first cohort. I got to learn about public policy directly. So I was now involved in two fellowships at the same time, one about non-profits and the other about policy. Can you imagine a better alignment of the stars?

Trans Equity Summit

Between the two fellowships I was doing a lot of informational interviews, networking with folks who were policy directors. Here is where things really took a turn. I heard about a Trans Equity of Summit. I was like, what is this?! And the city is sponsoring it?! I couldn’t wrap my mind around it. The day it was scheduled however, I was exhausted. I didn’t want to go, but I thought, this is historic. I need to go.

One of the recommendations of the summit was that more trans people apply for the city boards and commissions. I applied for the Youth Violence Prevention Executive Committee.

The other people on the committee were, in fact, executives, but I figured, I’m going to try. In my application I argued that I would bring on-the-ground experience to the committee. My students in Chicago were directly involved with violence and now I was working directly with immigrant youth. And, I had an analysis.

From the Summit to City Hall

During a breakout session at the Transgender Summit, I was sitting with a bunch of City Council policy aides. I told them, “I would love to have a job like yours. Can I do an informational interview with you so I can learn about your jobs?” One woman said, “Sure, come to City Hall and I’ll introduce you to folks.”

When I showed up at City Hall, by chance, Keith Ellison was there. I got to meet my congressman! I was super fanboyed out. He told me, “Hey, I’m have a transgender round table soon. You should come to that.” I was like, “Okaaay!”

That visit to City Hall was also the first time I met Andrea Jenkins and Ilhan Omar. I mentioned that I had applied to be on the Youth Violence Prevention Committee, and they said, “Let’s take you down to the mayor’s office. That is who appoints people to these committees.”

I was overwhelmed by how cool all of this was. The mayor’s office!! I got to meet Nicole Archibald, Mayor Betsy Hodges’ senior policy aid for public safety.

I was appointed to the Youth Committee. At our first meeting, Nicole sat me directly next to Mayor Hodges. Though the mayor generally does not co-chair city commissions, this was the committee that she did. She leaned over to me, which made me very nervous. “What brings you here?” She could tell I wasn’t an executive. I told her about hearing about this opportunity at the Trans Equity Summit. She nodded approvingly.

Senior Education and Youth Policy Aid For Mayor Hodges

The Youth Violence Prevention Committee asked me to speak at the launch of the Twin Cities My Brother’s Keepers event. After that, Betsy asked me if I would apply for a new senior policy aide for education and youth success. I got the job and dove headfirst in love with city government.

Jamar Clark

I was Betsy’s aide when Jamar Clark was killed. I think that is Betsy’s story to tell. I’ll just say that as her aide I have second-hand trauma from that experience. It was hard to watch somebody who in so brilliant—who gets it—be villainized in a way that did not produce any meaningful outcomes.

I volunteered to be her staffer that went to community events, engaging in challenging conversations around race and policing, even though I was not her staff for public safety. It was challenging for me, as a young Black man, to be navigating in a system that said his death was justified. Trying to juggle those multiple truths at the same time was very hard. But I would not have wanted to be anywhere else during that period.

Running for Fourth Ward City Council in 2016

I became involved in the fourth ward. Having neighbors that looked out for me and cared for me—and who I cared for in return—was a new experience. It was the first time I knew what community felt like. I decided I was going to run for city council against a 50-year family dynasty. Everyone told me I couldn’t win. People told me, go for it anyway, at least you will have a profile after this. But I knew folks were ready for something different. I always thought I had a chance even though people continuously told me I didn’t—up until the election numbers were called. There was about an 80% conversion rate: people who supported her, supporting me.

I began my campaign the night Trump was elected. I was at what was supposed to the ironic end-of-the-world election eve party. When, to our surprise, Trump won, I was running around being everyone’s political therapist, saying, “It’s OK y’all. Political change happens at the local level.” I wanted to be a part of that work. I knew, pretty well, what a council person’s job looked like. In the mayor’s office I had worked, intentionally, on the budget. I worked on Mayor Hodge’s legislative agenda. I was able, during the election, to have a concrete vision and put forward a pathway to achieve it—unlike a lot of first-time candidates who don’t understand jurisdictional authority—the difference between the mayor’s job and the council’s job in Minneapolis.I knew the job: what we do versus the county, the school and park boards. I had a good understanding of those boundaries. I knew, for example, the steps the city had to take to build certain kinds of housing. I was able to navigate the election far more informed than other first-time candidates.

Serving on the City Council 2017-2021

Nothing could prepare anyone for what happened in Minneapolis from 2017 to 2021.

I knew it would be challenging governing under a Trump federal government, but I did not realize how much things that happen on a federal level were going to impact us on the local level.

Working on a New System of Public Safety 2017-2019

I ran on—and have been working on—a comprehensive approach to public safety since 2017. In 2018 I got blasted because I had the audacity to move $1.1 million of a proposed MPD funding increase, to fund violence prevention. We didn’t cut any police. Still the police were organizing against me, and community members who were already angry that I was a council member in the first place joined them, spreading a ton of conspiracy theories about me. Yet, we were able to do so much with that 1.1 million! We permanently funded immigrant and refugee services and initiated bedside violence prevention.

In 2019 I was the lead negotiator between the council and Mayor Jacob Frey over the public safety budget, and I was able to get more violence prevention investment in that budget. These are things I’ve been fighting for really hard, since I’ve been in office, to create a system of public safety that thinks about the four main phases of someone’s involvement with crime and the criminal justice system: prevention, intervention, enforcement, and reentry. There are not clear lines between them—it is a flow—but all of them are opportunities to provide off-ramps from that cycle. I have focused on three points—prevention, intervention, and reentry—with most of my work on the first two. Enforcement falls under the mayor’s purview.

The Pandemic and Public Safety

We are in the middle of a once-in-a-century global pandemic that has disrupted the narcotic trade and put people out of work, caused kids to be out of school, and shut down after-school programing, yet the city council is personally blamed for a spike in crime and violence that has happened in every city in the nation.

I asked the chief of police, “Why are we seeing this spike?” One of the reasons he listed was the closing of the northern and southern borders due to COVID. That disrupted the narcotics trade, agitating competition between different drug-selling groups. The supply is down so they switch to fentanyl which is much more deadly.

I can’t do anything about the southern border. What we can do on the local level is legalize cannabis, expunge people’s records, invest in communities like North Minneapolis that have been the most harmed by the War on Drugs, helping people to access legitimate ways to get into the cannabis industry that will generate wealth in our communities.

Opioids? That is harder. I know prohibition doesn’t work with anything. Take sex work; when it is illegal, does that stop people from buying sex? No! It just creates more dangerous conditions for those involved. The same with drug use. There are strategies out there involving police working in community collaboration that involve focused deterrents and decriminalization.

When we shifted to having to cope with the severe spike in violence—children murdering each other in North Minneapolis—I was trying to bring forward a real plan to address the intense crime and violence in my neighborhood. I argued that if we address what is happening in North Minneapolis, there were city-wide implications: the car-jackings in South Minneapolis were related to the violence on the north side. But I could not get the support I needed from the mayor and the police department to actually implement them.

So, there was no plan! Public safety fit into the mayor’s purview, but we had to do something. I got a lot of blame—for death, for harm—when I feel that I was largely one of the only people who was putting everything I could into trying to stop it. It is easy to make me, a young Black man who is not unconditionally supportive of the police department, a fictional character in the media story about these wild and crazy progressives who hate the police. That has undermined my leadership and erased my thoughtful analysis about public safety. I have some serious concerns moving forward about the chilling effect this will have on other young Black people running for office. If I was a young Black person reading what people are saying about me, I would be like, “I’ll find another way to impact my community.” The treatment I have experienced has been uniquely toxic.

My Vision of Public Safety

I moved here to study public health. I approach public safety through a public health lens.

I just finished a master’s degree in Organizational Leadership and Civic Engagement and started a second master’s degree at John Jay College, in Criminal Justice and Police Administration. I am also getting an advanced certificate in Crime Prevention and Analysis. I got advice from people I admire who said, “Look, if you really want to build new systems of public safety, you have to understand how the traditional system works.” It is a rigorous program. I am four weeks into it now. I am glad I am doing it.

I chair the Public Health and Safety Committee of the Council. I know the policing system isn’t working in our city and that it is not reformable. You can’t just put in more officers of color, do more anti-bias training, do more de-escalation training and expect change. None of those strategies actually change policing outcomes. I knew these don’t work. I am learning what does. For example, I am learning how to address open-air drug markets to make them less violent. There are community collaborative approaches to policing that work. We need to work, as well, on having safe injection sites, more rehabilitation beds, and better social services; to deal with the immediate spike in violence there are real strategies that don’t require more police resources.

George Floyd, the Uprising, and the Powderhorn Park Mass Meeting

When the city was in the midst of an uprising and riots, white supremacists were burning down Black-owned businesses in my neighborhood and the police were nowhere to be found. I had to organize 300 Northsiders to post at different spots to protect the businesses and critical infrastructure in our community. I had to be organizer and community protector all night and city council member during the day. It was an amazing experience to witness and be a part of as a community member. As an elected leader though, it was traumatizing.

When George Floyd was murdered, a lot of folks began to jump on this comprehensive approach. It all has subsequently gotten derailed, because of the fact that I and some of my colleagues stood on a stage in Powderhorn Park and said we were committed to dismantling the Minneapolis police department.

First of all, we had no idea it would make international news. We took particular care to make sure that the pledge we were making was around a community engagement process to build a more holistic system of public safety. That event was not our event. It was put on by community organizations. We had asked that the words Defund the Police not be there. The problem was none of us did a 360 around the stage and none of us knew about the huge banner in front of the stage in bright yellow letters, until we saw the photo in the New York Times.

Now pretty much every bad thing that has happened in every big city in the nation is being blamed on us standing on a stage in Powderhorn Park, above a banner that said DEFUND POLICE. Someone needs to be blamed, and that moment has become the fall guy. Our standing on that stage has nothing to do with violent crime increasing in Chicago, Houston, Boston, New York. What is true is that what is happening in Minneapolis is not unique.

We Need to Reimagine Public Safety

I am still constantly being accused of saying that I wanted to abolish the police, when in actuality, I was the person who introduced the phrase “reimagining public safety” to the national lexicon. I said it during President Obama’s town hall in June of 2020, when I was a panelist. I had said then that defunding the police is not the route, that we have to be talking about re-imagining public safety overall. So after that, I heard now-Vice President Kamala Harris on CNN say “We need to re-imagine public safety.”

Defunding is a tactic, re-imagining is a strategy. The nuance of my perspective has never been fully captured.

Don’t Sacrifice Black Leaders on the Altar of White Supremacy

One of the lessons I walked away from 2020 with is that we cannot be sacrificing young elected Black leaders on the altar of white supremacy. The movement can’t just make these radical statements that elected leaders from marginalized communities are going to get the blame for, and then just leave us. I have heard people say I’m a minion of these movement radicals, but they don’t support me, they don’t defend me.

Still, I am out here trying to fight this fight.

I have my support in North Minneapolis which is all that matters. With the pandemic I have had to reset how I am engaging with folks in Ward 4. Before I had office hours, community circles, and community meetings. I tried to create a whole bunch of entry points and opportunities to engage with folks. Now, as an incumbent, I have people’s phone numbers, so I have the ability to call people when I want feedback on how I am doing. That is what I have been doing: cold-calling people and saying, “Hi, I’m your council member.” People actually really appreciate it.

The Charter Amendment: Creating and Implementing a New Department of Public Safety

We just had a public hearing on the charter amendment to transforming public safety, creating one department, so the police would no longer have a stand-alone department. Because I am the lead author of the charter amendment, there were some fairly vicious things said about me: personal attacks and assumptions about my intentions and motivations.

Still, I am focused on the concrete next steps that come out of this effort to transform community safety. In addition to getting the charter amendment passed, I am working on passing an ordinance alongside it that would flesh out the operations of a new Department of Public Safety, and I am organizing community folks who do violence prevention work, so that we have a coordinated network with street outreach people, who can be called so that we can find the right person to help each particular person in crisis.

Creating Public Policy that Creates Social Change

Public policy combined with policy implementation is what really matters. I can pass an amazing piece of legislation but if there is not the mechanism and will to implement it, it doesn’t happen. It is really important to work with the frontline staff when crafting policy, though it’s not always possible. In our work to create a Department of Public Safety, for example, I am actually working closely with the chief of police, (even though I get accused to not doing so). Of course, there are some rank-and-file police officers that are just not going to come along. They are the reason we need this structural change.

My policy-making process is that I partner with city staff. We develop a strong piece of legislation and an implementation plan at the same time, as well as a mechanism for community feedback to make sure that government operations directly impact people’s lives.

My Husband and Our Animal Kingdom

I am married to an amazing human: my husband, Lane Cunningham. He is the rock that holds me down and the glue that holds me together. He knew I would be in this position before I did. We met at a LGBT conference for activists in Colorado. He is from Missouri. When we fell in love I told him, “If you want to be with me you have to move to Minneapolis.” We got married two weeks after our marriage was legal nationwide. We own a house in Ward 4. I am very fortunate to have the life I do outside of work. Having a partner who is so present and supportive allows me to show up as my best self.

Lane and I have six dogs and two cats. Our animal kingdom are all rescues, with the last four coming from the City of Minneapolis Animal Care and Control. Caring for my animals is a huge part of my identity. They add and subtract stress in my life; they are so thankful and loving, and they tear everything up and pee on the couch. Lane has banned me from asking for more pets. I don’t blame him.

Animals are my constituents too. I brought forward a budget amendment that helped fund an animal safety-net program through Minneapolis Animal Care Control. Animals experience high levels of violence and they also need someone to advocate for them.

Final Thoughts: My Agenda for 2021

In addition to the charter amendment for a Department of Public Safety, I am working on a plan to eliminate childhood lead poisoning in this city. I am hoping we will be able to bring up the Upper Harbor Terminal Coordinated Plan by the end of this year. I am listening to Black entrepreneurs—about the systemic barriers they face, and business supports they need—and passing proposals put together by Northside business owners that would address those barriers.

I am only guaranteed four years in this office. I have been working my tail off every minute of every day, to get as much done in these four years as possible. This is year four, so I’m leaning in. If I am fortunate and blessed enough to be reelected in November 2021, then the work will continue.