I had assumed people who fought for queer rights would be anti-racist and not classist or sexist…The paid people on the campaign staff were misogynistic, racist, and elitist. It was a hard but valuable lesson. I am glad I learned it when I was sixteen. It helped me develop politically…

Today I am an urban, queer artist and community muralist. I teach art to youth. This generation of young people are so sharp. They will not tolerate homophobia, transphobia, or racism. They hate capitalism. They stand up to authority, and for each other.

— Katrina Knutson

Progressive Politics, Working Class Ethics, Hip Hop Culture

I was born in Minneapolis in 1977, to April and Jim Knutson and my big brother, Kieran. My parents were card-carrying members of the Communist Party, and were atheist/agnostic. Social justice was our religion. My parent’s activism, and growing up in Central neighborhood, have much to do with who I am. Progressive politics, working class ethics, and hip-hop culture were my major influences.

I went to Minneapolis public schools: Erickson, close to the river on the south side, then Bancroft, Field, Anwatin Junior High and South High school. When I was at Bancroft, I encountered a couple white kids who were racist in a violent and vulgar way. Some of the teachers were racist too. When I was eleven or twelve, we moved from Central to Kingfield neighborhood and I moved from Bancroft to Field school. I noticed the class shift. Field was a nicer school, and had better music, science and art teachers, more engagement with kids. The kids had access to more things. Their houses were nicer, most had their basic needs met. At first I thought, this is nice, I see less anger, hostility and racism.

Later, I looked back at my Field experience and realized there were also fewer kids of color than at Bancroft, and the better conditions at Field created an environment with less tension and aggression. I work in schools now, and I still think it’s pretty wild, how close schools can be—Bancroft and Field are less than two miles apart—and how different the resources they have to work with.

At Anwatin, I realized how kids are tracked into different units. The schools were desegregated in the 1980s and ‘90s, but they were segregated and tracked within the buildings along race and class lines.

As a kid, I loved animals and art and riding my bike. Not a lot has changed there! At age eleven, I got a pink and grey Huffy bike, and began exploring the city and also started babysitting, making my own money. I got into activism at a pretty earlier age too, not just with my family.

Early Activism

In 1990, me and three other friends at Anwatin Junior High staged a walk-out against the Gulf War. We made some signs, went downtown, and sat in the Skyways. Part of it was skipping school, but part of it was us really wanting to take a stand. The next day we came to school with black arm bands. A preppy eighth grade girl came up and said, “We want to protest the war too and we think what you’re doing is really cool, but we don’t want to wear black arm bands, we want to wear white ankle socks.” They wore white ankle socks every day. I remember saying, “That’s cool. We are going to stick with black arm bands. Thanks for your support though…”

While I was in junior high, Operation Rescue, an anti-abortion group, did a week of protests in Minneapolis. Me and my friend Molly went to the Basilica downtown to join a counter protest. That is when I started to meet my brother Kieran at protests. He had a huge influence on me. He actually did a lot of child care when I was little. My dad worked nights and for two years my mom had a job in another state. Kieran would get me off to school in the morning, pick me up in the afternoon and make me dinner. He is six years older than me. He was a great big brother, and he still is. He got involved in politics in his teens; becoming an anti-racist skinhead and an anarchist. He and some of his friends were at these Operation Rescue protests. That is when I first met a crew of anarchists and was introduced to their paper, The BLAST!

Anti-Gay Ballot 9 in Oregon

In 1992, I spent the summer in Portland, Oregon. Gary Schiff had this idea of bringing youth from Minneapolis to fight against anti-gay ballot initiatives in other cities. The referendum in Oregon—Ballot Measure 9—would have made it legal for GLBT folks to be fired and lose their rental housing because of their sexuality. Public schools would have been required to teach that homosexuality was “abnormal, wrong, unnatural, and perverse.”

I went into the project really excited. I was spending two months exploring a new city and working for justice. It was my first time spending the summer away from my family, fighting my own battles and formulating my own political views. I didn’t really care that we were working 40 hours a week for free—we got housing and $50 a week. I got to meet young queers from around the country. I learned that together we could be tough, smart, loyal and have tons of fun. It helped me come out. I realized these were my people and together we could change this fucked up world.

I learned two lessons that summer that were not fun, but they were important. I was almost always wearing my brother’s flight jacket that had Anti-Racist Action (ARA) and anti-Nazi patches. Portland had many Nazi skinheads with whom I had violent and terrifying encounters. That inspired me to join the ARA when I got back. I decided it was really important to organize against fascist street presence. If they aren’t confronted and chased out, they make cities intolerable.

The other lesson had to do with the campaign and intersectionality, though I’m pretty sure I didn’t know that word then. I had assumed that people who fought for queer rights would be anti-racist and not classist or sexist. I found out that was not true. The paid people on the campaign staff, the higher ups were misogynistic, racist, and elitist. It was a hard but valuable lesson. I am glad I learned it when I was sixteen. It helped me develop politically. I came back to Minneapolis and joined The BLAST! Collective.

The BLAST! Collective

When I was sixteen I began doing illustrations and writing for The BLAST!. I covered youth issues: injustices and protests in my high school, police brutality, the unfairness of curfew laws. I thought that police brutality and harassment against youth was intolerable. We had cops in the schools then and there were a couple instances of police brutality at South High School. One of my best friends was assaulted by the school officer. We organized a walk out and I wrote about it.

Everyone in the Collective (except me) lived in a house together near Lake and Chicago. In the “Blast House,” we had an office with really old Macintosh computers and printed locally, on newsprint. We used an early version of Photoshop. The bi-monthly newspaper was free in Minneapolis and to prisoners. Some of the people in the collective had done prison abolition work, so they had contact with incarcerated people. After those initial contacts, prisoners began writing us, requesting subscriptions.

Mostly, we paid for it out of our own pockets. We would have little fundraisers and people would send us donations. People in other cities would buy subscriptions. And we sold ads, mostly to local small businesses. To distribute it, we would leave it in stores; the same way City Pages did, but not as widely. Our circulation was 3-5,000 copies. I would bring it to South High and distribute it there.

When I turned eighteen and graduated high school, I moved into The Blast House. It was a big old house with lots of bedrooms, roommates and animals. The rent was very cheap: $200. This gave me lots of time to dedicate to unpaid organizing. I was able to support myself working three days a week at a coffee shop downtown called Moose and Sadies. I am still in contact with the owners, great humans who I loved working with. They just closed, due to the pandemic. People I met working there 20 years ago are still some of my best friends.

Growing up in Minneapolis, Conscious of Police Brutality

Being a young person in an urban environment, you are going to deal with police harassment. Black kids and other kids of color deal with it much more than white kids and in general, urban kids, poor kids deal with it a lot. White kids in South Minneapolis who run in multi-racial crews experience it. It was an issue that affected our lives.

I remember in 1989, when an elderly couple in North Minneapolis, Lloyd Smalley and Lillian Weiss, were killed. Like Breanna Taylor, it was botched drug raid; they had the wrong address. I was aware when the cops murdered seventeen-year-old Tycel Nelson in 1990, and a woman suffering from mental illness was shot by police in her Uptown apartment.

In 1992, a cop got killed at the Pizza Shack on Lake Street, very close to South High. As I remember it, for the next month it seemed like the police assaulted nearly every Black and Brown boy and young man in South Minneapolis. Multiple friends had that happen to them. They arrested eight people, who became known as the Minnesota Eight. There was a long trial and four of them went to prison for the murder of this cop. Others went to jail for decades on other charges.

I wasn’t one of the main organizers, but that case made an impression on me. I watched the way the police treat us as though they were at war with South Minneapolis, indiscriminately punishing men of color between the ages of fourteen and 40.

Anti-Racist Action and Cop-Watch

I joined Anti-Racist Action, the organization that came after the Minneapolis Baldies. ARA was national and to some extent, international organization. In the Twin Cities, it was a youth-focused mass movement to fight racism. Originally, we were targeting white-supremacist organizing, confronting them at First Ave and other clubs and bars, and stopping any events they tried to organize from happening. There was a political shift within our organization when we decided to widen our focus to include confronting police racism and violence, I supported that shift. I felt that combatting police brutality meant we would focus more on the racism that affected people of color in urban centers on a daily basis.

We started a cop-watch program. We would do patrols downtown. Of course, we didn’t have cell phones with video cameras; we had cameras and sometimes we had access to video cameras. Part of what we were doing was organizing. We would pass out flyers from 10pm to 1am when downtown was really busy. We would actually try to stop the police from arresting people by arguing with them very aggressively. That led to us getting arrested.

I got arrested two or three times doing cop-watch. Cops are scary, but I think it was good for me to get over that fear. We supported each other in those arrests. I got out within 24 hours. We had a relationship with Keith Ellison. Before he was a politician, he was a lawyer who defended us and victims of police brutality for free. He got all of our charges dropped. And if we did get a fine, everyone would chip in to pay it.

Meeting Graffiti Artists in Mexico City

When I was 22, I wanted to leave Minneapolis, to experience something new, to grow up a little, be more independent. I wanted to move to New York City. Molly, my best friend since junior high, agreed to go to move with me, but decided NYC was too expensive and too hectic. We made a deal. She wanted to go to Guatemala to a language school. We agreed that if she would move to another smaller city with me, I would go to Central America with her for a few months first.

We did go to the language school for a couple weeks, and then traveled around. In Mexico City—one of my favorite cities in the world—I spent time with friends who were graffiti writers.

Girls Militia in Milwaukee

After Guatemala, we moved to Milwaukee. I had been there a couple times for ARA meetings and I liked the industrial architecture. With that move, I left the ARA. Molly and I tried to start a Girls Militia. Milwaukee was economically depressed in the 1990s. Rent was cheaper than Minneapolis and going out to the bar was cheap, but wages were low and it was hard to find jobs. There was a lot of crime: robbing and mugging. There were also a lot of stranger rapes in our neighborhood. We organized with a few other women. We worked a little like cop-watch, only we would be stationary somewhere from 10pm to 2am on Friday and Saturday night. Women could call us and a couple of us would come and walk them home. The Girls Militia was short-lived. It wasn’t a great success story, but it was a cool idea.

Confronting Gentrification in San Francisco

After a year, we left Milwaukee. Me and Molly and my boyfriend at the time went to San Francisco. We lived in the Mission District which was beautiful, but I had to have three jobs to cover rent. One of my jobs was working at a corner store where I met everyone in the neighborhood. My boss was a fascinating human who was so great with people. Through him and the store I was quickly connected to the community. But whenever I left my neighborhood I saw the effects of early gentrification. It was 2000, after the first tech bubble burst. There were tons of people without housing and so much addiction, and also so many rich people engaged in frivolous spending. I saw that every day, while I was struggling to pay my rent. After a year I was ready to come home to the Midwest.

B-Girl Be

All during this time, graffiti was a big part of my life. I learned it by having mentors—painting with others engaged in the hip-hop world. I helped found Riot Crew. There is something political about painting without permission on property you don’t own, but my crew was explicitly political; committed to writing messages about events going on that were anti-war, against police brutality, pro-choice, that kind of thing.

Not long after I came back from San Francisco—2005—there was the first B-Girl Be hip-hop graffiti conference in Minneapolis. That was the first permission wall I ever did: on the side of the Intermedia Arts building.

I started to develop more as an artist. B-Girl Be became an annual thing, and I began working as a teaching artist. The third year, I was asked to curate the walls outside. After that, I began curating the Intermedia Arts gallery inside, showing my own work there and elsewhere. I started working with Hope Community’s mural program, Power of Vision, painting murals with youth from Phillips and other Minneapolis neighborhoods every summer. In 2019 I joined a cohort of artists through Hope to paint a mural on the old Franklin Avenue theater.

A Teaching Artist

Today I am an urban, queer artist and community muralist. I paint people, animals, urban and nature scenes. I do paintings that document and celebrate rebellions and rebelliousness. Teaching art has become my career. It can be exhausting and take energy from my own art, but I love it.

I enjoy working with youth and community and sharing my skills. Last summer I painted a mural with Avivo. They wanted to do a justice-oriented piece about what was going on. They were adults who had access to Avivo services or were involved in their arts program. It felt good to give them the skills and confidence to get their ideas and art on to a wall.

I work with youth at Loring Nicollet High School where I am an art teacher and at many other schools across the state, where I am a teaching artist. This generation of young people are so sharp. They stand up to authority, and stand up for each other. They will not tolerate homophobia, transphobia, or racism. They hate capitalism. They are so much more intersectional than people were when I was a teenager. I learn so much from working with them and absorbing the art and culture they create. They are done with white supremacy.

Tantrum Art Collective

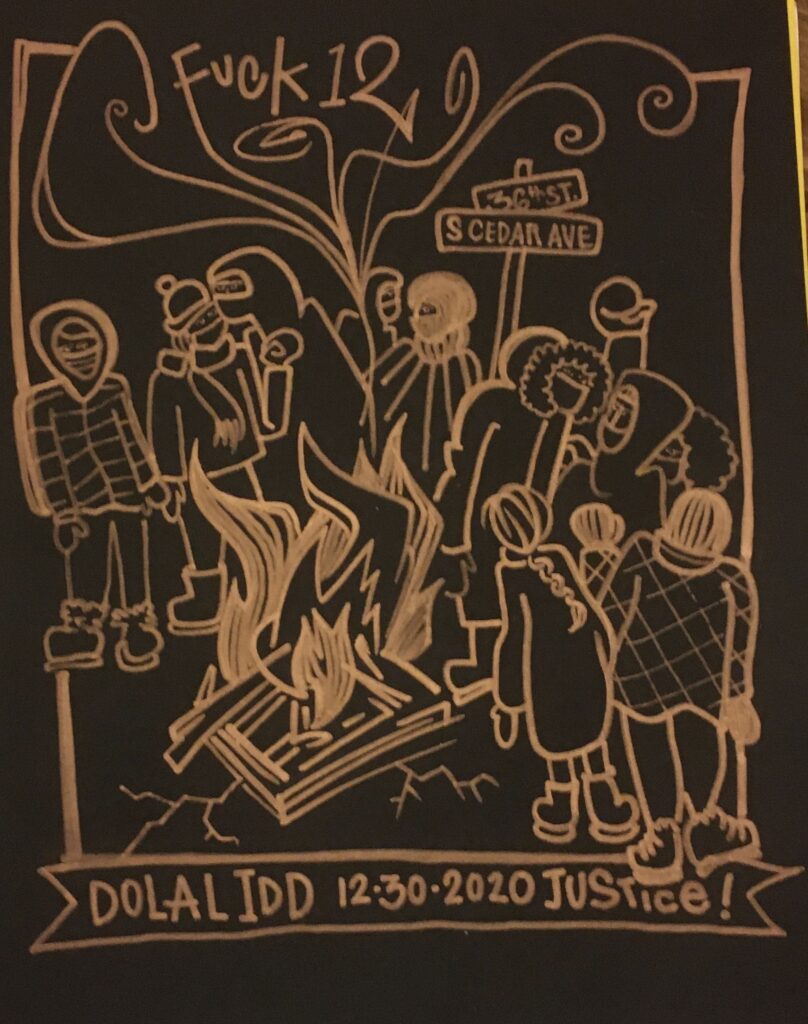

Out of B-Girl Be, we started Tantrum Art Collective made up of women and non-binary artists. These are the people I have been collaborating with for the last ten years—Michelle Spaise, Sayge Carroll, Kegan Xavi, Megan Longo, Nicole Amaris, Ivore Foreman, and Joy Spika—community and teaching artists who are committed to the idea that art is for creating change. Joy and I have been doing community collaborative murals in Phillips neighborhood for 10 years. Tantrum Collective had annual shows. The one I am most proud of was at a gallery on 38th and Chicago. The exhibit was called Rage, and the focus was on police brutality.

Using Mural Art to Break Urban/Rural Barriers

In the summer of 2019, Sayge and I got a grant from the Minnesota State Arts Board for a mural project in outstate Minnesota. We went to Bemidji and Red Wing and hired local artists in those communities to collaborate on a mural, breaking rural/urban barriers.

The idea for the project came when me and Sayge went to Bemidji on a whim and met tons of cool artists and had a great time. Of course, Bemidji is unique, surrounded by three reservations, with a large Native population, culture and influence. We worked with a Native elder and artist Nancy Kingbird and that was a really powerful experience. We had so many great conversations with all kinds of people. Painting a mural is a great way to connect. People are outside, they want to talk. You can have little conversations that sometimes turn into longer ones.

Sayge and I actually grew up a few blocks apart in the heart of the city, though we didn’t meet until we were adults. We felt there can be this kind of urban arrogance or belief that small town people are backward. This year with the elections, when we left the city we saw only Trump signs, but we know that’s only part of the story.

In Red Wing, we worked with an awesome artist, Drew Pelehos who knew everyone in town. So many people came by to connect and cheer us on. We stayed with a woman who worked at an art center in town. Having dinner with her and her husband and daughter, we got to talk about their fears of Minneapolis and our perceptions of small towns. It felt like we were making connections.

I do think it is possible to build an urban/rural coalition. We got the grant to continue the project this summer, but with COVID and the Uprising we didn’t end up doing it. We were supposed to go Hastings and Saint Cloud this year. We are motivated to try to continue the project post COVID.

2020

Everywhere, I hear people saying that 2020 was the worst year ever. I have some kind of reaction to that, though I understand that a lot of people have had it harder than me. I definitely cried tears of sadness in 2020, but I also cried tears of joy, watching brave and righteous anger running the streets. Things got broken open this summer. The Uprising in reaction to the murder of George Floyd has changed Minneapolis forever. It led to a global uprising against police brutality, violence and white supremacy, and I think that is beautiful and absolutely necessary. COVID and quarantine also made many of us rethink our needs and priorities, put energy into mutual aid and stand up for essential workers. I have never felt so inspired and hopeful about the possibility of social change.

On the personal front, Ty Bo Yule, the brilliant person I am married to, wrote a memoir, Chemically Enhanced Butch, that came out in 2020. We live on 4th Avenue, close to George Floyd Square, which I visit regularly. I fully support keeping this intersection autonomous and closed to traffic and the police. Much respect to the friends, community caretakers and residents of the square, including my nephew, holding it down. I am grateful to the young people of 2020.