Our movements tend to be reactive, not thinking three or five steps ahead, which is one of the reasons why we have President Trump. Sustainability requires intention, planning, and approaching the work from a perspective of hope, but not shallow hope—not putting a smiley face on hard issues. If you approach hard issues with complexity you find the pockets of resilience and possibility.

— Ricardo Levins Morales

Photo: Eric Mueller

Photo: Eric Mueller

Childhood in Puerto Rican Mountains

The way I approach political organization and art has its roots in the way I grew up playing in the forest. I had no on or off button, no screen, no blinking light. Games I played were invented versions of tag, climbing trees, making things up. A lot of the things that are basic to an eco-system are what I had to figure out if I was going to play.

My playground was the Western Mountains of Puerto Rico. We lived in a barrio of the municipality of Maricao. The town of Yaucu was about ninety minutes away. This was the most isolated part of the country, in terms of how long it would take to get to the lowlands.

In those days there was the sugar industry. That is gone now. But then–if it was harvest time–you would get stuck behind a cane truck driving three miles an hour, taking up both lanes on the windy mountain road to the coast.

There were three stores and a few houses along the road, not enough to call it a town. I went to a three-room school in back of a bakery. My economics education amounted to figuring out how best to spend my two penny a day allotment on candy.

Radical Heritage

My parents grew up in New York City. My mother is Nuyorican, my father New York Ukrainian Jew. In my father’s family were Communists, Socialists and left labor people. My great grandmother attended Emma Goldman lectures.

My father joined the Communist Youth, but even then, he and his friends were the dissident faction. The Party at that time said the main threat to world peace was a resurgent Germany. My teenage father and his friends said, “Nah, it’s the US.”

My mother joined the Communist Party when she and my father got together, when they were 20. They decided to move to Puerto Rico during the aftermath of the nationalist rebellion of 1950 and join the Puerto Rican Communist Party. They soon became part of the critical left within the Party. When there was a wave of repression after the Nationalists shot up Congress, Party leaders holed up in a little house on the road to Caguas and typed up communiques. My parents and their friends organized street protests demanding that the prisoners be freed.

My parents were soon blacklisted, unable to find work to sustain themselves. Under the advice of friends, they began looking for a piece of land to try their hand at self-sufficiency. In Maricao they grew vegetables and oranges. Their comrades would make pilgrimages up to the farm to talk about what was going on.

After a few years, my parents left the Puerto Rican Communist Party. They found its leaders to be sexist and full of themselves. Their friends Jane Speed and Cesar Andreu Iglesias, got purged. Many people who had good politics, got kicked out or left.

My father became involved in starting the Movimiento Pro-Independencia, which, a decade later, would become the Puerto Rican Socialist Party. When my father passed away, I found out that Independentista paper, Claridad, was started in 1959, when a young lawyer came up to our farm, to visit a journalist living with us.

In 1965 they published Escalera, an influential newsletter filled with analytical essays, named for an incident when they tried to hold a teach-in at the University where they were banned. They leaned a ladder on the outside of the University wall. The students sat inside. Speakers climbed the escalera and spoke over the wall.

Conciencia and Art

I started to draw early. My parents did the right thing and kept me supplied with paper. My mother did fabric art. She’d give me pointers if I wanted them, but mostly it was, “Just draw.” My artwork today is mostly black and white, with color added. If you took out the color you wouldn’t lose the meaning. I think that is because my instruments were mostly pencil and paper when I was little.

Every year we would go to the town of Laras in the coffee-growing region, to celebrate the anniversary of the Grito De Laras rebellion. People would crowd under the overhangs of storefronts so they wouldn’t bake in the sun as one orator after another paid homage in dramatic Latin American tones. I don’t know that I paid much attention or understood what they were talking about, but I could feel the passion.

My parents would tell stories about the Cuban Revolution, which was still pretty fresh. But they never lectured us on what to think. My sister says they taught us how to think not what to think, which is why I never had to rebel against their values. They were not shoved down my throat. When I landed in the States and was on my own, I had to assess for myself their ideas. I tested them, found them to be valuable, and so I kept them.

Eventually, when things cooled off, my father got a job teaching biology and revolution at the University of Puerto Rico in San Juan, so by the time I was old enough to be aware of my surroundings, my father was teaching in the cities and my mother was in the mountains. He would have to commute the four hours, stay a few days, and then commute back. As an educator of international Marxism, he had an influence on a generation young Independistas.

My mother had been active when they first got to Puerto Rico, but she was incrementally sidelined by the sexism in the movement. In general, women who should have been leading, were pushed aside.

Hyde Park, Chicago, 1967

When I was eleven, my father was purged from the University in an anti-Communist sweep. My mother wanted to leave Maricao to protect my older sister from some of the perils of being an adolescent girl in a small rural community. We went to Chicago where my father had a job offer.

Chicago’s Hyde Park had been a center for blues clubs. That was gone by time we got there. And it has transformed again since I left. The University has taken over much of the real estate. Even by the time the Obama’s moved in, it was on its way to yuppyizing.

In 1967, Hyde Park was known as the only integrated community– though that was still in pockets. The Blackstone Rangers and the Disciples both had a presence there. The Rangers had gone through an implosion a few years earlier. You had a lot of factions going around claiming to be the Rangers. It gave people street credibility.

The Chicago police were, of course, all over the place. They were the gang you really wanted to avoid. The gang kids hung out in the back streets. The cops controlled the main avenues. The thing about the kids’ gangs is that, for the most part, they knew they had to cohabit with you on the streets. They might hold you up for change, but they were not going to burn bridges with you if they could help it.

The cops had total impunity. You didn’t want to mess with them because they would never face any consequences for anything they did to you. I certainly suffered harassment, but not serious. My lighter skin spared me from the worst of it, although, if I was walking with a mixed-race group of kids we would be stopped. I think they hated that more than just a group of Black kids.

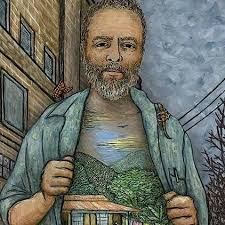

My father got a teaching job at the University of Chicago, which gave me and my older sister Aurora free tuition into the University Lab school. There was an atmosphere of hypocrisy there; control with a smiley face. It was creepy. They suspended me for my participation in the school walkout of 1970. I didn’t last long there.

In 1967, there was a lot of “urban rebellion” going on–as they like to call it. The anti-war movement swept up everyone at one time or another. I was a scruffy-headed kid going to demonstrations. I remember the morning when Che Guevara’s death was confirmed. I was getting ready for school. It was in the paper.

In 1968, when Martin Luther King was killed, I found out who he was. Everything came to a halt in our school and there were protests in the streets.

My parents joined Chicago’s radical movements. When my father died in 2016, I learned from a comrade that my parents shared a car with another family so they could donate the extra vehicle to the Black Panthers.

Cuba, the Summer of Che Guevara’s Diary and the Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia

Summer of 1968, my father had been offered an opportunity to spend the year in a department in Japan. We were all listening to a tape, Listen and Learn in Japanese, when a Cuba opportunity came up. My parents had been there in 1963 and had made contact with people involved in farming and biology. In 1968 my father was invited to help them set up a biology department. They had connected with him through the Puerto Rican Independence movement.

Recently my father told me they went to Cuba the first time, in 1963, to find out what was going on, because they felt as thought they had been misled about the Soviet Union. While we were there we laid the ground work for the project of the rest of his life: moving Cuba away from western model agriculture toward organic/ natural pest control. When the Soviet Union collapsed, even the bureaucrats realized they had to use organic methods. They thought it would be temporary, but those methods turned out to be so successful, they realized–this is better.

During that summer, Aurora and I were taking my brother Alejandro, who was a toddler at the time, around Havana, to movies, and to the zoo. I was copying the Cuban style of poster art. Aurora remembers my art made a bit of a commotion with the customs people, who called each other over to look at my cartoons of President Johnson.

We each spent a week in a youth camp, taking classes and running around. We drank cafe con leche for breakfast with pan de agua and yogurt with sugar. It took awhile for us to get signed up for food rations. Rations at that time included a quart of milk a day for children under three. While we were there it was elevated to age five. We got large supplies of guanabana-flavored yogurt.

When Che Guevara’s Diary was smuggled out of Bolivia that summer, it was published in mass editions and given away for free. Aurora and I would be downtown watching the lines around the blocks of people waiting to get in to get a copy of the Diary. He was really beloved.

Cuba in 1968 was an environment where you couldn’t help but pay attention. The rest of the world was visible. We saw Vietnam from a different angle. There were some Lao dignitaries in town getting press coverage. Places like the Congo and Indonesia existed in Cuba, (unlike here where they only exist when there is a disaster.) A Congreso with guerrilla movements from all over the world was held in Cuba that previous summer and I was reading about what was going on.

Cuba was a place where adults would ask twelve-year-olds their opinion. People asked me what I thought would happen next in the US. Some of those asking were ten years old. And I listened to people debating everything. I remember two old men at a bus stop arguing vociferously about the wisdom of building a spaghetti factory, donated by the Italian government, on the north coast. Is pasta appropriate in a traditionally rice-eating society? Everything was argued about. Another time I heard an argument about sexism, that began between a couple and spread to everyone traveling on the bus.

We were there when the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia. Aurora and I had taken the bus out to the beach in a former wealthy suburb filled with new housing for working people. Coming into the beach building, we saw people crowded on the stairs and at the counter with newspapers spread open, reading aloud and talking animatedly, as Cubans do.

The consensus was, “This is bullshit.” They sympathized with a small revolutionary country trying to forge its own path. They saw the Soviet Union invasion as threatening, although being an island on the other side of the world, they didn’t feel directly threatened, but Czechoslovakia was part of their family of nations trying to forge something different.

That night walking home, we heard every TV and radio tuned to hear what Fidel was going to say. Basically he walked a fine line, saying if a large country invades a small country they need to be transparent about why they are doing it, and have a good reason….

After my time in Cuba, I knew Havana better than Chicago. The city was safe for me to wander around. So many people had just learned to read during the literacy campaign, and they were eager to write me laborious directions.

When I came back to the States, I got on a bus and rode into Young Lords territory where they were creating a people’s park. Having been in Cuba all summer, I got on the bus and forgot I was supposed to pay. You paid in Cuba, but it was not a big deal if you didn’t have your dime. I did it so naturally the bus driver didn’t notice.

A Solo Trip to Puerto Rico & First Published Cartoon

In the summer of 1969 I went back to Puerto Rico by myself. It took me some years to absorb the fact that we weren’t going back. The move had been a major disruption of my life. I had been living in an environment of trees and clay, running barefoot. (I tried running in Chicago on the cement and ended up with foot problems.) I insisted that I needed to visit. Some friends picked me up in San Juan and dropped me off in the barrio. I stayed on the farm with anthropology students.

In San Juan, I visited the family of the editor of Claridad. That how my first published piece of art came about. They published my cartoon of Nixon pointing at the moon landing, while dropping bombs with the other hand.

Eavesdropping on Struggles of Other Peoples

My parents got involved in a group called New University Conference (NUC) made up of people who had been former SDSers, who went on to teach in Community colleges, universities and high schools. They sponsored a six-week training in Vermont that we attended in the summer of 1970. My parents were 40. Everyone else was 26, and then there was Aurora and I.

There were workshops on liberation movements, organizing, history, and publications from all over the world. It was from that conference that I started reading newsletters from Angola and Mozambique.

Eavesdropping had already become a major piece of how I learned about other people and other movements. Now I began reading the publications of second wave feminism and the gay rights movement. When Black women began to have their own publications, I read those.

I was fascinated with how the world looked from other perspectives. I devoured news from the People’s Translation Service that translated radical news from all over the world, into English. Through that source, I followed the revolutions in Portugal and Chile.

Chicago Black Panther Defense Committee.

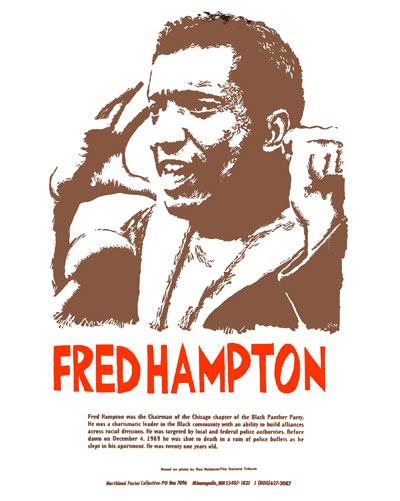

A turning point for me was when Fred Hampton was killed in 1969. After that I pivoted to real activism. My political home was the Black Panther Defense Committee on the Southside, which was not the neighborhood where the Panthers were organizing. The Defense Committee was all about solidarity–an interracial group. That was very formative of my politics. We did a combination of fundraising, street theater, organized protests of support when there were events that the Panthers organized, defended political prisoners, and sold newspapers.

The Young Lords started in Chicago. They were a Puerto Rican street gang that became increasingly politicized, linked up with the Panthers and learned how to do organizational work. Just like the Panthers, they led by example. People got the word in other cities and started their own chapters, in Milwaukee, New York, and elsewhere. The leaders were elders to me, but they were in their late teens and twenties. Manuel Ramos, a Young Lords leader was 20 when he was killed by the cops in 1969.

Though my primary organization was Black Panthers Defense, I sold Young Lords papers too. In 1970 when I started Kenwood public high school, I’d go to school with the Young Lord’s paper in one arm and the Black Panther paper in the other, selling them at school. This young woman with an Angela Davis afro saw me with both papers, stared me in the face and said, “What are you?!” I explained I was doing Black Panther defense. She then recruited me to help put out the newsletter for the Black Student Union.

I was absorbed into the BSU because there weren’t many Latinos in my school. Identity was seen as a foundation for solidarity not as a brand. There wasn’t any pretense that I was a wanna-be Black person, but in this particular political moment it wasn’t that unusual that I would be involved there.

At Kenwood the administration had turned over to the cops the “SDS” list of subversive kids and organizations, blissfuly unaware that the SDS no longer existed. We had an anti-war group dominated by the SWP. The BSU had been banned the year before. It was a prohibited organization. So we met in a darkened auditorium after school.

There was a lot of pretense. The biggest thing was dividing up the offices. Everyone wanted to be minister of defense because that’s the position Huey Newton held in the Black Panthers. Some of these guys had a brilliant scheme that they were going to get some guns and shoot a hall cop and then the students would rise up in insurrection. Fortunately they were all hot air.

We did organize a very effective walkout on the first anniversary of Fred Hampton’s murder, December 1970. There were high schools all over the city walking out, converging at this huge church where Black Panther Chairman Bobby Rush spoke.

Kenwood school was refreshingly repressive compared to the velvet glove thing at Lab School. The first thing you saw when you walked in were wire mesh on the windows and signs warning about the legal penalties for a whole list of behaviors. It was a relief. Everything was out in the open at Kenwood.

I dropped out of Kenwood in 1971. A few months later one of those hall cops killed a graduating student who had come back to visit, causing more protests and drop outs.

The Panther Defense Committee was an anchor for me. My first flyer was for the Panthers–a pig roast fundraiser.

I enrolled myself in an alternative school in the upper floor of the YMCA, for students who had dropped out or been expelled. It was a better environment. The teachers had been fired from other schools, which meant that they were really good teachers. But I didn’t last long there either.

Leaving Home as a Teenager

In Chicago, my mother, (p.14 of link), took advantage of being a faculty wife to get her free tuition and take her classes in Anthropology — hoping that learning about other people would be a window into solidarity. What she found however was an incredibly misogynist, racist, colonialist environment. She started drinking heavily. My father spent a lot of his time taking care of her. Aurora and I were raising ourselves and our younger brother Alejandro.

Aurora moved out when she was sixteen. I moved out when I was fifteen. I ended up sharing an apartment with three other teenage boys. One of the kid’s father had a background in the old socialist party. He knew it was the centennial of the Paris Commune in 1971. He said, “Lets call ourselves the “Centennial Celebration Commune”

The commune broke up when we got evicted. I circulated in various other housing situations with other youth my age, lived with my girlfriend for a while, in an apartment. We actually moved out of Chicago together. I drank steadily during those years, but I quit when I turned eighteen.

One thing about Chicago in the early 70s that made a lasting imprint on me was the intermixing of struggles. My sister and mother were in the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union. It wasn’t unusual for people in the Chicago Women’s Graphics Collective–part of the Women’s Liberation Union–to show up at the Black Panther Defense meeting, taking place at the home of the local coordinator of the Gay Liberation Front, to help us plan a guerilla theater action. The concept that we were all part of one movement was strong. Now the language is more, “I’m in this movement or that movement,” as though they are separate entities. Then there was this idea that we could bring down an empire, and if we were going to do that we would need each other.

That is not a baby boomer good-old-days narrative for me. It is as real now as it was then.

Getting Out of Chicago

A number of us at that age were just chaffing to get out of Chicago. There was a lot about it that felt oppressive. My girlfriend Freda and I looked at maps and eventually decided to go the Northeast. A couple people we knew were going to college in New Hampshire. We ended up in the mill town of Newmarket, New Hampshire. I got a factory job and she got restaurant work. There wasn’t much going on in terms of activism. I was still doing art of course because it kept me sane. When I was in Chicago I was doing song writing too, but I would hand my lyrics over to my musician friends. I pivoted more toward art in New Hampshire, when I was more isolated.

Freda and I had gotten together when I was 16. When we moved I was 18. Pretty long at the age. We broke up when she enrolled in college in Northern New Hampshire later that year. I eventually (1973-74) drifted down to Boston, the urban center of gravity for New England. I did day labor unloading docks, and restaurant work. I went from job to job in part because firms kept going belly up. The textile factory in New Hampshire–a center of the reactionary anti-union right-to-work movement, was the one place that stayed in business during this period of economic downturn.

In my late teenage years I was in a lot of physical pain. That bout of running on hard sidewalks wrecked my arches, ankles, and slowly worked up my spine. The week before I left New Hampshire I went to a chiropractor who took an X-ray and said, “Dude your spine looks like a pretzel.” Which was the nicest thing anyone had ever said to me. Validation. When I moved to Minneapolis I put myself under regular chiropractic care that steadily put me back together.

Union Organizing in Boston

For a while I lived by myself in a tiny apartment in Cambridge. Eventually I moved into a communal apartment with a group of Unitarian youth, and got a job at the Beth Israel. My fellow hospital workers were in the middle of union drive–my first involvement in the labor movement.

I got on an internal organizing committee with people working laundry, kitchen, transportation, lab tech, and secretarial. Some of those hospital services today are jobbed-out. I was in janitorial. We put out a newsletter. I was making little cartoons–caricatures of management.

Departments were organized along ethnic and racial lines. Janitors were African American and Caribbean. My crew consisted of one US Black, one Cuban, one Barbadian and me. One of the crews that cleaned ER was made up of Trinidadians, with one Barbadian. Management promoted the Barbadian to supervisor, even though he didn’t have seniority. Two weeks later he said, “No, I’m keeping my job.”

That union drive was a major education for me.

Getting to Minneapolis

I was tired of moving around. I thought, if I don’t make a decision where I want to settle I will end up here by default. I was from really rural, I had landed in really urban. Boston felt like a small town at first compared to Chicago, but then it started to feel like a big city and I wasn’t sure it was what I wanted.

On a road trip with friends, I came to Minneapolis for the first time and met some people. The city seemed relatively clean by US standards. It had a bridge across the river just for bikes, (I didn’t realize that was just a University thing). Most important for me, it had the benefits of a college town without being dominated by it. I didn’t want a Madison, Ann Arbor, or Berkeley.

I was at a networking conference in Wisconsin, when I entered into a conversation with three other people looking to move. We compared our shortlists. Minneapolis was the one that showed up on all of them. We went back to our homes, packed up, with a plan to “meet in Minneapolis before the snow flies.”

That meant leaving the hospital union campaign. I told them I was leaving to take care of a sick brother, so as not to impact the morale of my coworkers. We did lose that union drive. I learned some things life- long lessons about how to and not to organize from that first labor experience. I started tweaking management messages to form a labor message:

I hitchhiked to Minneapolis, (my hitchhiking odometer at that time was 26,000), arriving on Halloween, 1976. The one person from my group who already lived here, found a house on Franklin and Columbus Avenues, near “broken glass park” (now Peavey Park).

Arriving on Halloween, it felt like I was the last one to arrive before they closed the gates for winter. I had no idea what was where. Everything was covered in snow. I would walk down streets with nobody on them. 1976-77 was the period of the collapse of social movements– undermined by repression and the rise of the nonprofits. So, not only was I landing in a new place, where it was winter and I didn’t know how to get around, but also there was the new political reality to navigate.

On a bulletin board–the internet of the time–I found a Tai Chi class. Mostly, I worked. I got a janitor job at the Blaisdell Y. When summer came, there was an alternative health fair in Loring Park. We did our Tai Chi there. I wandered around and found a reflexology booth. They were massaging people’s feet and talking about the importance of foot care to overall health. Since that day I have given myself over 30,000 foot rubs.

Establishing an Artist Life in Minneapolis

Back in Chicago, I had discovered screen-printing in an issue of Ramparts Magazine. I sent away for a booklet and taught myself how to do it in my bedroom. I came to Minneapolis with a plan to do more of it.

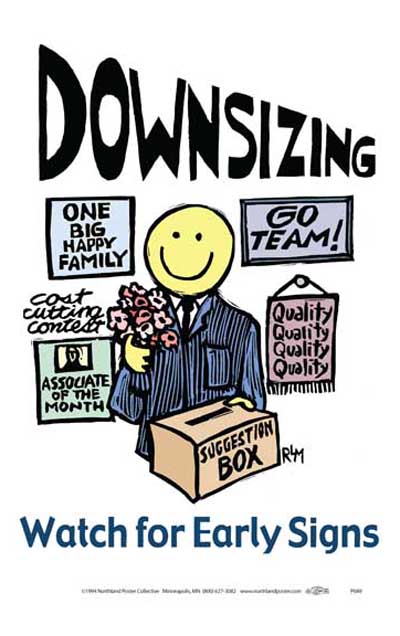

I created a screen of Woody Guthrie’s quote that begins: I hate a song…” It was my runaway best seller for the next fifteen years. I had to cut out each letter. I had no idea it would sell ,so I had dismantled the screen and I had to redo the whole thing again, letter by letter.

To raise the money for a trip to Puerto Rico, I went around to organizations and offered to make them a poster about their issue for $200. It was a vehicle for finding out who was organizing in the Twin Cities. I found Food for the World, Northern Sun Alliance, INFACT, and the Third World Institute. I got involved with INFACT for a while, and raised enough money to get to Puerto Rico. Before I left, I heard that the the Cedar Riverside tenants were on the strike. They were having meeting at the Riverside Cafe. I gravitated toward that.

Organizing Against Nuclear Power Plants.

Back when I lived in New Hampshire, Aristotle Onassis got the idea of putting an oil tanker super port on the coast of Durham, NH. The town fought the project. I got involved in creating cartoon characters on factory walls for the campaign. It was defeated. Just before I left, there was news of a nuclear power plant they wanted to install in Seabrook, New Hampshire. People were weighing if that was a good or bad thing. In the aftermath of the super port, many were dubious.

In 1976, before I moved to Minneapolis, I went to Philadelphia for the Bicentennial Without Colonies demonstration. It was a coalition of the Black Panther Party, the American Indian Movement and the Puerto Rican Socialist Party. Sixty thousand people marched through the neighborhoods of Philadelphia, ending in a big rally, in a sudden downpour — a mass multi-generational gathering of people of color.

Around that same time, 200 White environmentalists marched at the Seabrook Power Plant under construction and got headlines. It was a shifting of attention, a turning point.

In the summer of 1977 when I was in Puerto Rico, I was getting letters from Minneapolis activists saying, “There is the new power line movement happening in rural Minnesota. We have to take you out there.”

They took me out to Lowry, MN to a power line construction site. We bent some material and got arrested. I had a felony trial. That, and Northern Sun Alliance, became my focus for a while.

At that time, Indigenous folks were connecting with farmers over what they called energy wars. The initiative came from AIM to build a wide coalition. Uranium mining, coal mining and power lines were destroying lives and livelihoods for both groups. Kids from the Red School House would go out as a group.

Clyde Bellecourt spoke in Delano. He told the farmers they were the “Indians of today,” which of course was a stretch, but it flattered them and got their attention. Later, when another AIM leader, Russel Means, was stabbed by another inmate in Sioux Falls, the farmers organized a car caravan to protest outside the jail.

Farmers were toppling power lines at night. Laurie Witzkowski and I went through our court process and got off. Alice Tripp, a farmer, ran for governor, and Paul Wellstone managed her campaign. Alice was also a teacher. She was a one-woman farmer/labor coalition.

Chile Resistance Movement

Dean Reed was a rock musician who became popular in Latin America. He went to Chile in 1970 and protested in front of the US embassy after the CIA overthrow of Allende. He was living in East Germany when he learned about the power line movement when he was here on a musical tour.

He came to Minneapolis, met Marv Davidov--went to a protest in Delano, Minnesota and got arrested. Reed’s arrest in Minnesota made headlines all around the world. East German school children were writing letters of support. Yasar Arafat wrote a letter demanding his release. That poor rural Minnesota judge didn’t know want to do with letters streaming in from all over the world.

Marv gave me a call. While in prison, he and Dean Reed had talked about the new Chilean revolutionary folk music–Nueva Canción. Maybe we could do a concert? I said. Yes!

That is how I got together with Paula Holden. I had loaned my Nueva Canción record stash to friends in Puerto Rico. A mutual friend introduced us and said,”Paula has your records. Quilapayún, and Inti Illimani.” Soon after we moved in together as, “persons of interest to each other.”

With Victor Jara Memorial Fund and the New Song Movement, we supported refugees and people in the underground resistance. We did fundraiser for solidarity actions for Grenada, El Salvador and Nicaragua. Our concerts paired international musicians with national and local artists. One time we had Quilapayún and Holly Near…

I worked on a little local newspaper called the Cultural Worker, with others including Heather Baum, Kathy and Leo Lara, and Marilyn Lindstrom. The purpose was to highlight political artists. The stirrings in those days was to integrate cultural work into activist movements.

Northland Poster Collective 1979-2009

In 1979 a number of us started the Northland Poster Collective. We met at a conference and hatched the idea. We found a space on Franklin Avenue and Bloomington, across from what is now the American Indian Center.

NPC eventually moved to third and Washington, downtown, and a warehouse district. The building later became Sex World. There was a buzzer to get in and no phone. The first of artist spaces. The Red Eye was there.

Everyone in the collective brought different forms of art–charcoal, watercolor and learned how to adapt them to screen printing. Our work was beautiful—-and it sat on the shelf. We had not considered the question of how to sell them.

We created a plan to publicize our work. We arranged exhibits, did outreach to activist groups. WAMM’s first signs came out of that outreach. We created a brochure, and then trooped down to the Minneapolis Public Library to look through the Yellow Pages of cities across the country looking for radical, Black power, feminist, and gay bookstores. We put together a mailing list, sent out our brochure and starting getting some orders.

We began to get letters asking us to distribute the art of other artists who didn’t know anything about invoices and shipping. We responded far and wide, and began doing consignment. We did that a couple of years.

We noticed there was very little labor art. We got a good response and we put out our first color catalogue. The response was tremendous. Labor unions and organizers were buying it up. That remained a central feature of Northland for the 30 years of its existence. We joined the sign painter’s union. We were creating work with a union bug.

Once we moved to Lake Street we got T shirt-making equipment. We began doing buttons and bumperstickers, beer cozies, and baby garments. A favorite onesie read: “I’m a little Wobbly.”

We had to learn how different movements were structured. The environmental movement was horizontal and localized. The labor movement was multilayered with decision making centers at different levels. People might buy for a local or at a mass scale for a national.

The labor movement might buy 500 T shirts for a protest. The feminist movement bought shirts and buttons as individuals for identity purposes.

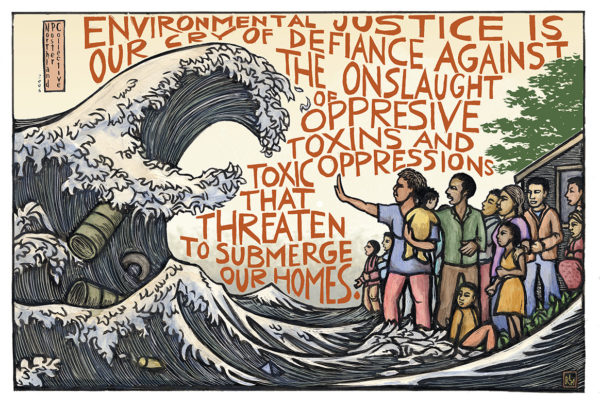

The Poster Collective was very hand-to-mouth. We found out the color catalogues were a mistake–too pricey. We thought about our work not in terms of markets, but constituencies. We tried to meet needs, not create demand, find ways to service everybody. We felt politically loyal to small rag tag groups, prison support, LGBTQ centers and environmental justice groups that didn’t have big budgets. We were creating materials to serve those movements. For example, I did a poster on environmental justice.

At the time, most of what they were using as visuals were graphs and flow charts. There was nothing that spoke to the heart.

We talked about how to support other people’s work and fill in gaps, not hone in on other peoples’ turfs. At the same time we had to figure out how to survive.

In the 80s I began to attend an event in DC called the Great Labor Arts Exchange, a gathering of cultural workers in the labor movement. That gathering continues to this day, with musicians, artists and actors within the labor movement and working class communities. Over several years a few of us worked hard to create an addition to that conference, which was a conference on creative organizing, to attract rank and file unionists to create art and use it in their organizing. People didn’t necessarily have to be artists to engage in this creative political work.

Working with Northland, I pretty much knew what organizing was going on, because people needed art for their projects. It meant we were in touch with the body language of many social movements. We knew what people were hungry for. We tried to reflect that in our catalogue.

A fair amount of what we did was in response to what was going on, like a picket sign depicting the Shah of Iran when he came to power with support of Jimmy Carter.

The owner of our Lake Street building was a far-right Republican and a terrible businessman himself. He owned multiple properties and was always in financial trouble. He was friendly to us. He came in one day all excited because he was listening to Rush Limbaugh and Rush had mentioned me by name in connection to the Columbus Quincentennial.

He would ask us to write out of check to a different entity every month– which we refused to do. It turned out the money we were paying him was not reaching the gas company. We had no heat in the building for two winters.

We tried to keep our ear to the ground and produce art that would address the next need. But if it didn’t sell we would be stuck. We created a whole bunch of new art around immigration issues, but no-one was buying it so we took it out of our catalog, just before the massive marches for immigrant rights in 2006.

We had some bad luck. I remember driving with a car full of expensive color catalogues, about to mail them out, and hearing on the car radio that the economy had just collapsed.

During those years I often said, “I love my work but I hate my job.” When we shut down, politically we had never been in better shape. And we had killer customer service. By the end we were paying ourselves consistently, but with the economic collapse of 2008 we didn’t know if we would be able to keep that up.

Alliance for Cultural Democracy

In 1984, I went to Chicago to attend the Alliance for Cultural Democracy as a representative of Northland, to share what we did. The Alliance championed the kind of work we and others did on a national level.

The Alliance became a network. It was very strong in small cities and rural areas. There would be a conference every year in different parts of the country. There was no staff, so coordinators from different regions would get together to plan the national gatherings. A local organizing committee would form wherever the conference was going to be held. The alliance also published newsletters.

We felt that art mattered in social movements. It was a struggle to convince some sectors. There was a gathering in the 1980s of labor organizers and cultural workers, and virtually no organizers showered up. It wasn’t taken that seriously. But we won that battle! Today, every emerging movement has its art-build days and its focus on creative visuals. It is hard to remember that was a hard-sell.

In 1987, we had a board meeting for the Alliance for Cultural Democracy at the Highlander in Tennessee. That was my first exposure to the Highlander. I knew it was a center for CIO organizing in the 1930s and Civil Rights in the 1950s. It was fascinating to be in that environment. There were photos of King and Rosa Parks on the walls, from when they came for training. Miles Horton was still alive when I was there.

At the time I became involved in ACD and got onto the Board, there were very few members of color. After we focused on the quincentennial, that complexion changed, until it was majority people of color. The programming itself drove who came into it and who took leadership.

1992 Columbus Quincentennial. Changing the Narrative.

I had read, through Independista Press, about a group of activists in Puerto Rico outfitting canoes in South America and following the migration route of Tainos, planning to arrive in PR in 1992 in time for the 500th anniversary of Columbus. I came back and pitched the idea to the Alliance. We had enough time to prepare for 1992.

The Alliance accepted that idea and we started putting out material. In 1991 the Alliance was here in the Minneapolis. I was one of two national coordinators at that time, while we were focusing on the quincentennial.

We put out a free newspaper called Huracán, a national networking tabloid aimed at coalition building, opening a space for everyone’s stories. We had contributions from Native Americans, African Americans, and Latinos. Japanese American juxtaposed the years 1492 and 1942 to bring in the interment camps. Some bold Italian Americans said, “We have better things to celebrate than Columbus,” wrote their truth and got tremendous pushback from their community.

Material for Teachers and Local Coalition Building.

There was no centralized leadership for this wave for cultural opposition. At one time I contacted Leonard Peltier to sign on as honorary chair for the entire movement. That never actually consolidated. He did call back when I was out of the shop and for various reasons that have to do with incarceration we never were able to connect.

The US Government effort to commemorate Columbus eventually fell apart. The director of it was a Cuban immigrant union-buster out of Miami who ended up under indictment for corruption. Our work tarnished the image of the Quincentenial so badly that Coca Cola and other major sponsors pulled out. It was millions of dollars in debt with nothing to show for it.

Teaching Columbus in the schools has never been the same. It put wind in the sails of the movement against racist mascots and toward renaming Columbus Day. It was a lesson for me in the power of narrative. There was no demand other than that the story be told differently. There were no concrete gains to be made, and yet it felt like it shifted things. It tied narratives of Indigenous genocide, slavery and colonial oppression and connected them into one story that was able to infiltrate into popular consciousness.

Radicalizing the Labor Movement: Labor Notes

In the 1990s, I became involved with Labor Notes. It started with going to their conferences to sell merchandise, but eventually I became a member of their advisory committee. I did that for about 20 years. As a part of that work, I got involved with a local group called Meeting the Challenge: Gillian Furst of the Teamsters who worked at Honeywell, Randy Furst from the newspaper guild, Peter Rachleff, Gladys Mckenzie from AFSCME, postal workers, service employees, machinists, auto workers and others.

We produced a one-day labor conference at Macalester every year, dealing with issues the labor movement wasn’t talking about. Some unions were joining with management engaging in cooptation. We were one of the few places where we were discussing how toxic that was. We did that through the decade of the 1990s. We presented an annual solidarity award–a quilt made up of union T shirts from the Poster Collective.

Networking Organizations and Social Movements

In the mid 1990s, members of the Writer’s Union, Third World Organizing Center, Teamsters, and Southwest Organizing Committee, founded the National Organizers Alliance–a center for organizers. I am drawn to endeavors that work on a larger scale, bringing people together to build movements, not just organize campaigns. The NOA had a founding conference at Evergreen State College. It grew. The larger conferences had 500 people and tied in historic and current movements. There would be workshops with veterans of SNCC, and Welfare Rights, passing knowledge to the next generation. There was a struggle in the beginning to define “organizer.” I was one of a faction that fought off attempts to define it in professional terms. The professionalization of organizing was already in process….

In 1986 Paula and I had our daughter, and in 1989, our son. I went down to half time during those early childhood years- as long as we could afford it.

Cultivating the Organizational Soil: 2000s

On September 11, 2001, the poster collective was having a strategic planning retreat. We immediately interrupted and sent messages out with a poster, a print shop in Madison printed them for free. It was used very widely.

There was a little group called the Freire Center. In the aftermath of 9/11 about ten of us began meeting. We began having potlucks. We stayed together for several years. We called ourselves the Visions Collective. We were trying to do some of the missing work–intersectionality.

There was a moment when we were meeting and an anti-war march passed by on its way to Powderhorn Park. All of our instincts were to reach for our coats. But then someone said. What will matter most in the long run? Our deep deep clarity or our participation in this protest march? We sat back down. Our movements tend to be reactive, not thinking three or five steps ahead, which is one of the reasons why we have President Trump.

One of things I experienced, and the Northland Collective as well, having lasted thirty years, that we have ebbs and flows: periods governed by liberals and periods governed by arch reactionaries. The stories that we need to tell during each of those periods are vastly different because our political and historical memories are so short. During the Reagan and Bush years we needed to remind people that mass movements have not disappeared from history, they are simply in remission. They will be back. In periods of mass movements we had to remind people, these don’t last forever, you have to prepare ahead. Sustainability requires intention, planning and approaching the work from a perspective of hope, but not shallow hope, not putting a smiley face on hard issues. If you approach hard issues with complexity you find the pockets of resilience and possibility.

I have had to navigate issues around visibility. My exhibit--the 50 year retrospective of my work at CTUL this fall–brought up this contradiction to me. I don’t believe in creating celebrities out of people. I get some of that treatment, yet I need visibility in order for my work to be effective. I have tried to be intentional about my visibility. I think of myself as an Ella Baker organizer trapped in a Martin Luther King world.

Storytelling and Public Speaking and Writing

My work has continued to diversify into various forms of storytelling, public speaking and writing. Beginning about ten years ago, I started noticing that organizations that never wanted to hear from me before, were suddenly offering me money to speak.

It was becoming clear to them that the hamster-wheel model of organizing wasn’t going to move anywhere. Groups are looking for answers in the declining era of the empire when the ruling elite is less interested in funding non-profits and social efforts, putting the nonprofit sectors into crisis.

When I turned 50, I decided to be intentional about what flavor of mid- life crisis I was going to have. The traditional cultural options available were not for me. They had unadvertised downsides or were class inappropriate. Red sports cars are not my thing.

Researching Social Movement Strategies

I decided I would do something more useful. I gave myself permission to research the movements I had participated in. It was a time when many people engaged in movements in the 1960s and 70s, were evaluating their experiences.

I wanted to know: what was healthy and restorative about the Black Panthers and what were the weaknesses that led to their dismantling? Why did the women’s liberation movement take a hiatus between suffrage and second wave feminism, while in Latin America there was continuous struggle?

What was the nature of the different strategies for liberation in Africa and why did some of them backslide? Why did the African National Congress end up forming the government of South Africa when their leadership was profoundly dysfunctional in many ways and much of their work continually backfired? How did South Africa sink into neoliberalism so quickly after liberation?

I consider Tecumseh one of my strategic mentors. I wanted to know: what were the balance of forces when the Indigenous leader was organizing in the 1800s? Why was his movement, which was contemporary with that of Simon Bolivar and Toussaint L’Ouverture, ultimately defeated when in fact they could have changed the course of US history in major ways?

I looked at all of these issues with the understanding that everything is composed of toxins and nutrients. So I generated a lot of writing which informs the educational work I do now. I learned, dealing with some of the traumatic histories in my own family and life, the ways trauma impacts organizing. I realized that my art was reframing traumatic narratives for traumatized people–an essential part of the healing process. Listening to Malcolm X’s speeches helped clarify that, because that is a lot of what he was doing through his oratory.

Trauma and Resilience Workshops

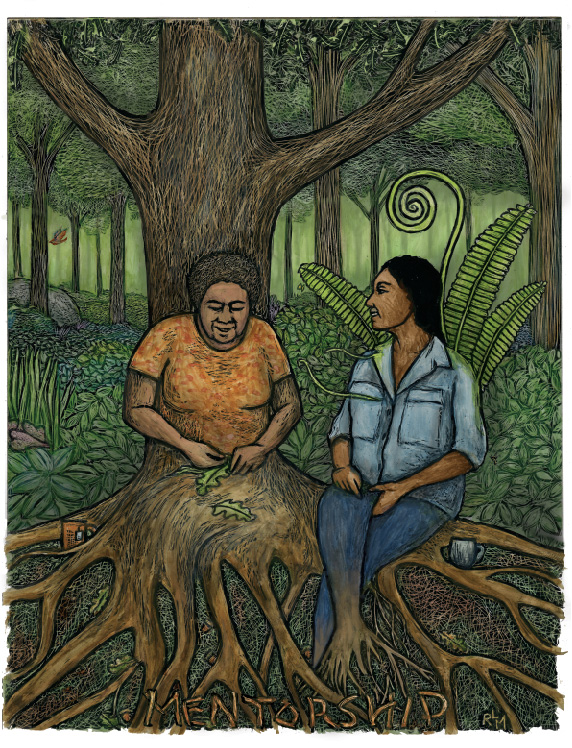

About seven years ago, I began partnering with Molly Glasgow, who does healing acupressure and organizing, to do trauma and resilience workshops for organizers. That work is unlike campaigns when you have a win at the end. It is about cultivating the soil, which is my organizing model. Soil is more important than seeds.

Over time, steady patient organizational work can shift the consciousness. It can happen in a widespread rapid organizing strategy such as the consciousness raising groups of the women’s movement, or it can happen in slower, but still organic ways. I have been helping organizers think about what the moment means for them.

I see past cycles, tipping points of nutrition and depletion–all things I learned from playing on the mountainside. The long-term writing I am doing now is about how that organizing works, so it can be a teaching tool. One of the most satisfying things is seeing these concepts percolating back in current movements around the country.

MPD150 and Movements to Defund Police

The idea of MPD 150 was to hijack the narrative of the 150th anniversary of the Minneapolis Police Department, formed in 1867. We began in early 2016. We were a group of activists pulled together from within the Minneapolis organizing ecosystem. We did not represent organizations, although some were members of existing groups. We didn’t want a coalition of organizations because we wanted to avoid turf jealousies. We did not want to steal anyone’s glory. We did want to put wind in everyone’s sails, providing momentum and resources for anyone working on police issues.

The first year we were completely under the radar, working in teams. At our height we were probably five dozen people. We did police history, interviewed people who interface with the police, like social workers, social services organizations, and domestic violence centers. We fundraised and wrote zines. We partnered with a northside research team of high school students who had done a lot of street interviews with people impacted by police violence. They made their archive available to us.

A Beautifully Designed Document

We produced a print report. It was important to have a tangible, beautifully-designed document, divided into past, present, and future. The historical section showed that the only thing police have consistently done well is racial profiling. Police reforms have just been a distraction that allowed them to continue with that principle mission. The present, focused on how they are currently impacting the things we say we need police for, like safety and social service. The future was about the issues that policing pretends to address, and how they can actually be addressed, shifting resources to take away the social service functions the police don’t do well anyway, to others who do, moving toward the ultimate goal of police abolition. We wanted to change the narrative to police abolition from a naive fantasy to the only pragmatic solution and course for the future. After all, the police were set up to keep Black people in servitude after the Civil War.

We had a held public launch event that packed 300 people into CTUL. It showed the depth of readiness in the community. Even before that, news of our work seeped into City Council races. Politicians were holding press conferences to tell people what a bad idea it was. It was wonderful. Once the report came out we had a vehicle to bring to conferences, high schools and colleges, groups working on policy issues, and social work departments.

We created a wonderful audio book using the local voice talents. We had an exhibit that with art commissioned for each section. It was on display in North Minneapolis at New Rules on Lowry, for about five weeks. We had panel discussions that went with the exhibit.

Based on a Hopeful Strategy

It was creative, horizontal work. Because it was based on a hopeful strategy, we avoided a lot of the problems of ego. People were able to work with full hearts and listen to each other. People cycled in and out of the work, and there was space for that. Other people stepped in. The hopefulness of the work encouraged people to volunteer resources.

We were intentional about not centering ourselves. We always gave credit to the groups that came before. We did not have press conferences whenever the police did something wrong or ask to have the microphone at events. We invited people doing this work in organizations to speak at our events.

After the exhibit we had a period of reflection. A panel of elders and neighborhood organizers reflected on our work.

We decided this will be our last year. Our goal was not to create a permanent organization, but instead a permanent change in the narrative. Right now we are working on explaining the nature of “community policing” which is a pacification strategy that comes out of counterinsurgency strategies of the 1970s, but is disguised as a new way to make policing non-oppressive. We are breaking that down. High school students are working on exposing the oppressive nature of police in schools. We are creating a case study of our work so that other people can learn from it.

Hurricane Maria

Hurricane Maria has had a number of permanent impacts in Puerto Rico, not only on the ecology and infrastructure, but also on consciousness. It really blew away the colonial reasoning that we need Uncle Sam, because if anything bad happens to us we will be protected. Hurricane Maria was a bad thing that happened. Uncle Sam, not only did not help, but harmed us in many ways, under the pretense of helping.

The people who rose to the occasion were people on the ground, creating self-sufficiency centers, food distribution, house-to-house surveys, clean up. The myth that we are a small helpless island without capacity was buried with a stake in its heart. That’s a lesson that can not be unlearned.

Puerto Rico used to be completely food self-sufficient. Recently it has been importing 80% of its food. That is beneficial to corporations but not to us. The forms of agriculture that survived the hurricane were those in which traditional methods were used–the few places where crops were being grown under forest cover rather than in open tilling; the places where traditional root crops were grown, provided a base of food for people. So food self-sufficiency has become a goal again.

The Hurricane brought the Puerto Rican Diaspora and Islanders Together

The two groups have often been played against each other. Puerto Ricans on the island were conditioned to see those who left as not really Puerto Rican; people who perhaps don’t speak Spanish well, or at all, even though, on the mainland, they are treated like spics by White folks.

When the hurricane hit, the diaspora rose up and provided relief. Here in Minnesota, health professionals went on multiple trips to provide immediate physical and mental care. Young people organized massive drives, got donations from entities like the Minnesota Twins, filled whole planes with essential goods, got Delta airlines to donate transport. It was a massive outpouring. I can’t claim to have taken any lead in that. The shop produced buttons as a benefit. It was marvelous experience, seeing the way people pulled together. In Puerto Rico, the diaspora were respected and honored for their role–as part of the Puerto Rican family. That is a wonderful cultural change.

When you are colonized dignidad is one of the things you can hold on to. Eduardo Galeano once said that dignidad has set off revolutions in Latin America. The leaked phone transcript displaying the Governor’s disdain for people was a bridge too far–a violation of dignidad. The mass uprising that overturned the governorship, showed that an insult to self worth is not something people can take lightly.

Responding to the Rise of Authoritarianism in the US

Engaging in movements since I was small, and growing up in an environment that taught me the ecology of the forest, I see the world in terms of rhythms. That spares me from despair at the rise of Donald Trump. I would never have predicted it, except that in the declining era of an empire, especially with the decline of economic resilience of the elite, the system does lean toward authoritarianism. In fact, that was happening under the neoliberals that came before Trump. The World Trade Organization and later the TPP, reflected the decision of the elite to monopolize all power and create mechanisms for overruling labor, environmental, civil and economic rights passed by governments all over the world. Trump came in with a different model –more directly fascist– but still representing the elite consensus that, “It is time to take charge.”

After the 2016 election I thought, “Ok, we are in a different time now, one that requires different tasks.” I did not think, “The world is coming to an end.” For people with a more liberal world view–those trained to look just at what it is in front of them and not the bigger picture, it looked as though the world was ending. The assumption that we were on a linear progression, that we are becoming more enlightened, got blown out of the water.

I used to say things that sounded crazy–like, “The US Civil War was never resolved,” and “Fascism has deep roots in this country and could reemerge.” In a similar vein, others have been talking about climate change for decades. Those things don’t sound so far-fetched now.

Make Unorganized People a Better Offer

There are times–like now–when the left and the right are both rising and the middle is eroding. In these times there are strategies you can use to peel away the support of the right. My father used to say, “There are very few people who have a vested interest in oppression. Most people who are fighting us are either fooled, bribed or frightened into it. Those are all potential allies.” In the labor movement they are called the unorganized or the stampeded.

I am influenced by the Black Panther model: you organize those unorganized people, not by meeting them halfway, but by making them a better offer.

Minneapolis Interview Project Explained.