We guilt each other when we need to get on a plane to see a dying family member, though getting those bombers out of the sky and ending chemical warfare would do far more to address climate change. It is time to make those connections and build a really broad movement for peace and justice and to save the planet.

—April Knutson

Iowa Childhood

I was born in Fort Dodge, Iowa, where my father’s parents lived. My mother grew up in Des Moines. When I was born, my father was in the US Navy, stationed on Tinian Island where the Enola Gay, took off. That was a heavy thing for him to live with.

He got back from the war when I was five months old and we moved to New York City. My father was in a Ph.D. program in American History at Columbia University. I was in New York from age six months to two years, but I swear I have memories of it; the ocean; the city skyline.

We returned to Iowa. My father was a professor at Grinnell College, which is a great school in the middle of corn fields. Unlike other faculty brats, my family believed that children of all backgrounds should be in public schools together, so I went to the Grinnell public school, but there was a lot at the college that I participated in. I took college French, because the public school only had Latin.

My mother was very involved in Democratic Party politics in Grinnell. I have early memories of door knocking with her, for local, state and national candidates. She was also a member of the League of Women voters.

In 7th grade, my father had a Fulbright scholarship to do research in Scotland on the early life of Andrew Carnegie. I spent a whole year going to a great school in Edinburg. It exposed me to a rigorous education, with courses in geography and history beyond the US lens. While in Scotland I listened to the BBC. That was the year of Little Rock and Sputnik. The British broadcasters decried and ridiculed the US. That was a seminal experience for me — important to see the US from a critical perspective. I never heard anything like that in Iowa. My parents got the New York Times, but there was never that kind of critique there.

When I graduated from high school, I was eager to leave Iowa. I went to Swarthmore. I had planned to major in political science. I took the upper level courses. I even did a year study-abroad in Sweden, focused on politics. Come junior year, I had all the credits to complete the major, but had not taken the required introductory course. I registered for the course, bought the textbook, written by the instructor and cracked the book. Its thesis was that all nations should seek to accomplish US style democracy. I knew I couldn’t complete the course without creating a huge ruckus. I majored in French.

Summer of Love, Winter of Discontent

Between undergrad and grad school, I spent 1967-8 in San Francisco: the summer of love and the winter of our discontent. I lived on Bush Street close to downtown and Chinatown, and worked office jobs. My apartment cost $100 a month. I was making $3-400 a month. Even so, there were many homeless youths on Haight and Ashbury. They had fun in summer and fall. It got worse in the winter. People got cold, women were abused and drug addiction made it hard for them to find jobs and a place to live.

San Francisco is where I met Dick Mulloy, my first husband. He left high school his senior year to join the Marines. When we met he had just been discharged. Our first meeting he said, “How can you even talk about Vietnam if you’ve never been there?” I said I knew more about it than he did—a very arrogant thing to say—but he still wanted to see me again.

We got married and moved to Connecticut, where I enrolled in a graduate program at Wesleyan University.

Introduction to Marxism

At Wesleyan I took Contemporary Theater with Lucien Goldmann, a well known Marxist literary critic. The way he taught was so different from the dominant deconstructionist method. In Goldman’s class you had to know the economic class of the author and their life experience and education. Deconstructionists don’t think that art reflects reality. Marxists believe that art necessarily reflects social conditions, but that reflection might be distorted, based on the artist’s experience. We read Beckett and Sartre. I don’t think we read any women, but it was really great. I started writing my papers from a historical perspective.

Getting to Minneapolis—-and the Communist Party.

I never wanted to return to the Midwest, but Dick’s family was from Minneapolis and he really wanted to go back. I agreed to try it for a year. I transferred to the U of M graduate school in the French department, and began working as a TA. That was 1969. I was 24.

I loved Minneapolis right away. I was amazed at the progressive politics, how informed people were and the affordable cultural opportunities. Even on my TA salary, I could go to the Guthrie and the Minnesota Orchestra.

But mostly, it was the political scene that attracted me. The first moratorium against the war was that fall. As a Teaching Assistant, I told my students I certainly wasn’t going to be in class. I didn’t get disciplined by the department for doing that.

Someone handed us the Daily Worker along the parade route. The paper reported that the two goals of the Party, were to Free Angela Davis and end the war in Vietnam. I was completely in accord with both of those goals. The paper listed the locations of all the Party bookstores in the nation.

The last HUAC hearings that interrogated suspected Communists, was held in Minneapolis in 1964. In 1969 the Senate Committee on Subversion, led by Strom Thurmond, was here. They labeled anyone involved in the anti-war activism, including the pacifist socialist U of M Political Science professor Mulford Q. Sibley, a subversive. The Cold War witch hunts sent many people on the left, underground.

The Communist Party in Minneapolis was literally underground. They had a bookstore in the basement of an apartment building on Franklin and Chicago Avenues. Betty Smith, the CP district organizer in charge of Minnesota and the Dakotas, lived in the bookstore.

Dick had joined Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) before we left San Francisco, and started reading Marx in Connecticut. He didn’t work very much, so he had time to track down the bookstore. There was a sign outside that said simply Bookways.

Dick began to hang out there a lot. Betty Smith arranged for a long-time activist from Milwaukee, Sig Eisencher, to come to Minneapolis for a weekend in the summer of 1970 to educate us in Marxism-Leninism, political action and how the party was organized. In the fall of 1970 we joined the Party.

At the time we joined, the Party in Minnesota was still underground. We were instructed not to reveal our membership and not to reveal the names of our comrades. We found out about our first club meeting when someone we had not met before, knocked on our door and handed us a slip of paper with a date, time, and address written on it in pencil. This procedure was both exciting and spooky. I felt part of a secret society.

Along with several other comrades, I pushed for greater openness and a public presence for the party.

The party always viewed me as suspect. I had a “bourgeois” background. My mother came from a wealthy family in Iowa; my father was from humble origins, but he was a college professor. “A very unstable background,” according to Party doctrine. Dick, on the other hand, was from a solid working-class family. And he was an anti-war Vietnam vet.

Supporting Angela Davis

When Davis was arrested, I immediately identified with her. We were both graduate students who had studied in France. I wanted to be part of her defense. I was appointed State Secretary of the Committee to Free Angela Davis in 1970. I was pregnant with my son Kieran then. I would be speaking and making arrangements for Angela Davis while preparing to have a baby. When I was eight months pregnant, I was on Channel 11’s noon-time news show, talking about Angela’s case and announcing a big action. They let me announce the event! That was May, 1971.

The Free Angela Davis Committee provided the opportunity for the Party in Minnesota to have a public presence. Our fundraising events always listed the CP as a sponsor, along with civil liberties and peace and justice groups. People who signed petitions for her freedom often asked us if we were Communists and wanted to talk with us about the Party.

Incarcerating Angela Davis was one of the stupidest things the ruling class ever did. People who supported her release were open to Marxism, and to the Party of which she was a member. I think, apart from the 1930s, the early 1970s was the highest point for recruitment into the CPUSA, in large part because of Angela.

Others were drawn to Communism as a result of their opposition to the Vietnam War. Many young people were convinced that Ho Chi Minh was right.

Opposing the Vietnam War: March of 60,000 and Blockade of Washington Avenue.

After Angela was freed, I focused on organizing against the Vietnam War.

The biggest protest I have even been on in the Twin Cities —up until the Women’s March just after Trump was inaugurated,—was the anti-war protest in May of 1970, when 60,000 people marched on the Capitol. You need to remember how much smaller the population was then, to realize the enormity of that event. Of course the moment was singular: the bombing of Cambodia, and police killing of students at Kent State and Jackson State.

The March started at the U campus, walked down River Road, near enough to other campuses — St. Kates, Macalester, Hamline, so those campuses could join. But it wasn’t all students. A lot of people from the neighborhoods joined in too. We walked by Humphrey’s house. Muriel was out on the front lawn waving at us. That was pretty amazing, especially considering Hubert’s performance in 1968.

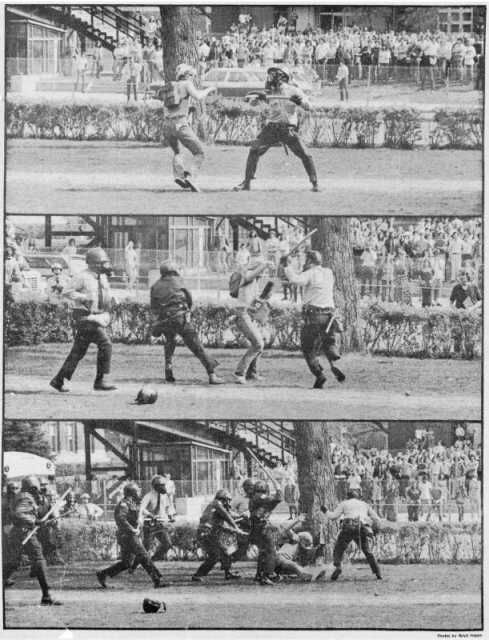

And I’ll always remember the blockade of Washington Avenue, after Nixon blockaded the Haiphong Harbor in 1972. I had a baby, so I couldn’t stay all night. But students did stay all night, prohibiting access to the East Bank. U of M President Malcolm Moos was out of town. The acting president didn’t know what to do. He called Mayor Charles Stenvig – a former (and future) cop. He and Hennepin County Sheriff Don Omodt sent in a tactical squad, and helicopters that sprayed tear gas onto campus and Dinkytown. It was an all out assault. People got sick and a few people were beaten, including a Daily photographer. The tactical squad followed the students onto campus. You know, campuses have historically been places of refuge. This was a violation of that historical contract.

The assault backfired. It was a beautiful May day. This was before the campus was air conditioned so all the classrooms had their windows open. The buildings filled with teargas. Professors and students who planned not to participate were forced out of their classrooms. They were horrified by the response of the police and many joined the protest, amplifying the anti-war movement.

The police sprayed Dinkytown and Stadium Village as well, filling the interiors of small businesses—many of whom were independent and progressive (unlike now when independent entrepreneurs are priced out of the University neighborhoods.) Some of them were already supportive, but after the tactical assault the whole Campus area business community was furious at the police. Many more posted leaflets in their windows advertising anti-war meetings and events. It was an interesting phenomenon to study how overreaction by authority can increase support for a popular movement—not that I would ever try to incite that kind of response on the part of the police — but they should learn from it.

We in the CP, did struggle with the Socialist Workers Party in the anti-war movement. I was instrumental in saying we had to work with them. When we were trying to unionize the TAs, I worked with Gary Prevost who was in the SWP. I was criticized for doing that. The people who were criticizing me were from New York or Chicago where the Party was dominant. I argued that Gary was a good organizer and we were forming a strong union together. I fought the criticism and wasn’t expelled.

We had to work together. There would never have been a march of 60,000 if left groups didn’t work together.

Life in the Party 1970s

After the Vietnam War things did slow down. Some people faded away from the Party. I was still pretty active. I enjoyed the meetings, the political discussions. We continued the struggle for socialism in the United States, in solidarity with the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, convinced by party leaders that these countries had in fact achieved socialism, and a better life for people than capitalism could offer. We were also assured that existing socialism was much better for the environment and the future of the planet than capitalism.

I and a couple of other young people pushed successfully for the Party to be open. In order to have electoral campaigns we had to collect signatures to get the candidates on the ballet. As participants in mass campaigns like the grape boycott, we began to hand out leaflets about CP forums. Some of the clubs began to have open meetings.

By the late 1970s and early 80s, almost everyone was above board, though we still promised we would never out anybody who didn’t want to be. The bookstore moved above ground too, to a site in Dinkytown, and was renamed the Paul Robeson Bookstore.

We lived near Stadium Village when we first arrived and later moved to just off Como and 15th. In both places I walked to school and work every day. That second neighborhood was full of graduate students with babies.We had a cooperative babysitting cooperative. No money changed hands. You earned a point for every hour you took care of a kid and you could use those points to get a sitter for your children. It was wonderful.

Party Structure and Practice

Being in the Party was a warm, comradely experience until the last couple of years. They were my best friends. I loved talking with them about what was going on in the world. There were monthly meetings in our local clubs where we reported what we had done and mapped out what we were going to do. Sometimes I was in the South Minneapolis neighborhood club and sometimes I was in the University club. In the University Club, the educationals were fabulous. In the 80s we had a member who was from Nicaragua and others who were steeped in what was happening in El Salvador.

We had quarterly district-wide meetings with representatives from each club in Minnesota and the Dakotas. Kieran came with me too many of those meetings. There was always an agenda, but often we went off into freewheeling discussion about current events. Some of our discussions were quite heated.

At the District meetings one person would represent each group. There was one person who came to those meetings from the Dakotas. He was a union organizer, working in the beet processing plants — very big business in the Dakotas. He would report on the radicalization of beet workers.

I remember one of the first district meetings I attended, there was a guy from Warroad MN who had a farm with sheep on it. He wanted us as the Party to allow more hunting of wolves because wolves were attacking his sheep. I sat there with my mouth wide open. The consensus of the group was that should not be a priority of the CPMN’s legislative agenda.

We conducted a Marxist School in Northern Minnesota at our cooperative park on the Mesabi Range. It had originally been a logging camp for the IWW. The CP bought it in the 1930s. The nearest town was Cherry, where Gus Hall grew up, not far from Hibbing. It was an amazing tract of land, with beautiful evergreen trees. Right in the middle was a lake that had never had a motor on it. Absolutely pristine. When the Party bought it, the maps didn’t show the lake. There was a pavilion with a dance floor. There were square dances every Saturday. We often had district meetings there. In addition to our schools on Marxism Leninism, we had children’s camps where the offspring of comrades could get together and talk about what their parents were up to. That was a good thing.

Everyone who came to the Range school to teach us, (they were usually from New York), knew something about Minnesota, and tried to learn more before they showed up to educate us. Gus Hall , Chairman of the CPUSA, was from Minnesota. His parents were Finnish Wobblies and early Communists. Comrades from Northern Minnesota fought in the Abraham Lincoln Brigades and died in Spain, fighting fascism. There was an oil portrait of one of them at the main lodge at the park.

I remember James Jackson coming. He was one of the best leaders I knew in the Party. He was not from New York. He was from the south, was African American, a Party leader in Louisiana. I remember a talk I had with him about the Spanish Civil War, the Lincoln Battalion, and the role of artists and intellectuals in the struggle for peace and democracy. He said the biggest mistake the British Communist Party ever made was to send a battalion of poets to the Spanish front. Many of them died. That was very moving to me.

I met Jim Knutson at a gathering at the Mesaba Park. We met again at Peace conferences in Chicago and Milwaukee. He was an accomplished folk singer with a magnificent voice and strong stage presence. We were married in 1975, and had our daughter Katrina in 1977. Jim adopted Kieran. We took both children to Party meetings and FLA meetings. We used to joke that our kids did not know how to behave in church services, but they knew how to get on the agenda at meetings! Our daughter was on local television news when she was only a few weeks old. We had taken her to a demonstration to free the Wilmington 10.

Communist Electoral Politics and the Farmer Labor Association

We worked on Party electoral campaigns, collecting signatures to get our presidential and vice-presidential candidates on the ballot in Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota in 1972, 1976, 1980, and 1984. It was relatively easy to get third party candidates on the ballot In North Dakota and Minnesota, as both states had experience with third-party movements in the 1930s: the Non-Partisan League in North Dakota and the Farmer Labor Party in Minnesota. The Farmer Labor Party had elected two governors of Minnesota and a Congressional representative, as well as many members to local governing bodies.

South Dakota had a different history and a very different political climate. The Wounded Knee Occupation was fresh in people’s minds, and they were very hostile to “outside agitators” coming into their territory. They required nearly as many signatures as Minnesota, with only a fraction of the population. We spent many hot summer days in South Dakota in vain.

In the late 1970s we got involved in the re-formation of the Farmer Labor Association. The idea was to bring the F and L back into the DFL. The FLA would work both within and outside of the DFL, supporting candidates who did and did not have DFL endorsement. Our first big success was Karen Clark.

The State Senate seat was open and Karen agreed to run. She was a nurse, involved in the nurses’ union and was an out lesbian. We got to the State DFL convention and Linda Bergstrom, who was the District House Rep for 62A said, It’s my turn to be State Senator. You can run for my position.” After consulting with us and other associates, Karen agreed.

Karen was great at talking to small groups and was a fabulous door- knocker, but she had a tiny voice. Jim was a singer. He coached Karen in how to project and give speeches to a large audience. She won handily and eventually became an accomplished public speaker. Living in the Phillips neighborhood, she was easily endorsed and she was re-elected with huge margins until she retired in 2019.

Brian Coyle was another FLA candidate. He ran for US Senate and for Minneapolis Mayor as an independent before winning the City Council Ward 6 seat in 1983 as a DFL candidate. He died of AIDS in 1991.

Jim ran for School Board as a Communist and got the FLA endorsement. While working with the FLA we simultaneously worked to get Communists on the ballet, once running a candidate for Minnesota Governor. I didn’t see any contradiction in doing both. There wasn’t a Communist who wanted Karen Clark’s position.

In 1984 I worked very hard for Jesse Jackson. Gus Hall ran that year. Many comrades around the country like myself, refused to collect petitions for Gus Hall that year. In 1988 he did not run. That year Jesse Jackson carried every precinct in Minneapolis.

There was some red-baiting in the Farmer Labor Alliance. I was on the executive body which met twice a month, before and after the general membership meetings which were once a month. I always went home right after the executive meetings, to be sure my children were in bed and to prepare my classes for the next morning. The rest of the executive body adjourned to a bar. One evening, a young woman from the FLA executive called me to ask “What is your agenda?” I asked her what she meant. She said that the night before, after the executive meeting, the chair of the FLA had said that I was following my own agenda, dictated by the CP, and that I did not adhere to the principles of the FLA. I answered her as best I could, saying that my concerns and the issues of the CPUSA were completely compatible with the principles and goals of the FLA. Then I called the chair, and we had a long talk about red-baiting and the FLA. I was never asked to resign from the FLA executive.

Jim was running his own campaigns for Minneapolis School Board as a Communist and he was endorsed by the Farmer-Labor Association. He made it through the primaries, but did not win the general election.

Sometime in the early 1980s, Betty Smith moved to New York, and the new District Organizers for the Minnesota-Dakotas were Matt and Helvi Savola, a couple from Wisconsin who had done a lot of work in farm cooperatives and lumber camps. They enjoyed working in outstate Minnesota and in the Dakotas, but felt uncomfortable in the Twin Cities, especially with the large University of Minnesota club.

When Matt Savola died suddenly of a heart attack, an extraordinary woman from the Iron Range moved to Minneapolis to be the new co-district organizer with Helvi. Helen Kruth Leviska had lived and studied in Leningrad, worked in Finland, taught in New York, then moved to the Iron Range to be among her fellow Finns. She felt perfectly comfortable with all the demographics of the party in Minnesota—workers, farmers, doctors, lawyers, professors and students. She encouraged open discussions at all meetings and a completely open presence for the CP. She ran twice for state auditor and spoke at candidates’ forums at the University and in community gatherings throughout the state.

Helen also offered to run for Governor of Minnesota in 1986 and asked Jim if he would run for lieutenant governor. A spring meeting of the district committee approved the campaign, and we started collecting signatures to get Helen and Jim on the ballot. In the middle of the petition drive, Gus intervened. He called Helen and Helvi and said that we should not run against the incumbent governor, Rudy Perpich, who was an old friend of his from the Iron Range.

It is true that Perpich was a progressive DFL governor, but we wanted to push him further on workers’ rights and social justice issues. After all, in 1972, Gus and Jarvis Tyner had run against McGovern, arguably the most progressive major party candidate ever nominated for president. But we had to stop our campaign.

Leaving the Communist Party

The last time I saw Helen, before she also died suddenly, was in 1989, right after the fall of the Berlin Wall. She came bursting into a meeting of the University Club, held at the home of Doris and Erwin Marquit, and confronted them, saying, “Why didn’t you tell us the truth about the problems in the GDR?” (Doris and Erwin had spent two academic years in East Berlin, teaching at Humboldt University.) I think if Helen had lived, she would have helped those of us in Minnesota who wanted open discussion about the problems in the existing socialist countries and maybe she would have had some influence on Gus Hall, since they came from similar backgrounds, although she had much more education than he did.

The party in Minnesota, particularly in Minneapolis, objected strongly to the publication on “Communist morality” which decried homosexuality. Mike Zagarell was sent out to deal with the Minneapolis clubs. I remember him saying that the working class would never accept homosexuality and that we should stop supporting the gay rights movement. We had a long heated discussion at our party book store. At one point, Mike said that only in Minneapolis and San Francisco were comrades supporting gay rights.

After Helen’s death, the Party decided that the Minnesota-Dakotas district needed a new District Organizer. Lee Dulugin was dispatched to select a comrade from the district, as evidently it had been decided that no one from New York could be spared. She interviewed me twice and talked with at least two other comrades. I was selected. She asked me if I would serve without pay. I said that I could contribute much more if I could be paid a small amount so that I would not have to teach so many courses at the University. At that time, I was teaching French as a Lecturer (adjunct faculty member) earning $3000 per course. Usually I taught 2 courses per quarter, 6 courses per academic year. I said that if the party could pay me $3000 per quarter (about $1000 a month), I would teach only one course per quarter. She said she would take this up with the leaders in New York. Meanwhile, she said that there would be great perks for the job, such as travel to resorts on the Black Sea. I said that I couldn’t take a trip like that without Jim and the children. Well, of course, I never got a trip to the Black Sea, and I never received a dime from the Party.

In fact, as I soon found out when I started attending the National Committee meetings at the Party building in New York City, the Party was falling apart. There was an active, organized opposition to the leadership of Gus Hall. Comrades, especially African-American comrades, had been upset for years at what they perceived as less than full support of the party for the campaigns of Jesse Jackson for President in 1984 and 1988. In Minnesota, comrades had worked very hard with the Rainbow Coalition on the Jackson campaigns, along with the Farmer-Labor Association. We did not really know what was going on in the rest of the country. Helvi never gave us full reports of any discussions or disputes during the National Committee meetings. She just parroted what Gus Hall had said.

At my first National Committee meeting, I passed out a resolution from the University club (the Elizabeth Gurley Flynn Club) calling for a complete, open discussion of what had gone wrong in the GDR and the Soviet Union. We called for all clubs nationwide to discuss the analysis of Joe Slovo, Chairman of the South African Communist Party. I was reprimanded by Judith LeBlanc, who told me that I could not leaflet a meeting of the National Committee and that if I ever did it again, I would no longer be admitted to a National Committee meeting. I never “leafleted” another National Committee meeting but did attend meetings in New York City comrades’ homes, after the official sessions were adjourned, to discuss the lack of internal democracy and open discussion in the party.

The crisis was coming to a head. Before the National Convention of December, 1991, in Cleveland, Ohio, we tried once again to call for open discussions of the collapse of existing socialism and of the leadership and direction of the CPUSA. In the Minnesota-Dakotas district, all clubs elected their delegates to attend the Cleveland convention. Then these delegates were supposed to be approved at a district meeting. Our district meeting was scheduled for November 2, 1991.

On Halloween 1991, Minnesota was hit by the worst blizzard in years. We decided to hold the convention anyway, and to just approve the nominations made by all the clubs in the district. Unbeknownst to me, Sam Webb had flown in a week before and had been lobbying against me and the Twin Cities clubs in outstate Minnesota and the Dakotas. Somehow, despite the blizzard, he arrived back in Minneapolis in time for the district convention. He tried to stop the proceedings, but we voted to approve the club delegates anyway. But when we arrived in Cleveland, we were denied our credentials.

We all joined the Committees of Correspondence meetings in a space near the hall where the CPUSA convention was being held. We did not try to get into the Party convention. Those who did try were stopped by Cleveland police (!) or assaulted by Gus Hall’s henchmen.

Jim and I, along with several other comrades from the Twin Cities, attended the Committees of Correspondence meeting in Berkeley in the summer of 1992. I came away from that meeting very disillusioned, feeling that the leadership of the C of C had also stifled full discussion, in the same way that Gus Hall and his cronies had. Jim stayed with the C of C for several years.

So, after more than twenty years–half of my life at that time–I was no longer a member of the Communist Party, nor any other Marxist organization. But my life did not change that much. I remained active in the peace movement and in electoral politics. My children were also very active in the struggles against the wars in Central America and against police brutality here in Minnesota. Jim and I often had to go to the city jail to pick them up and bail them out.

I co-taught a course on Marxism at the University of Minnesota, spoke at a number of campus forums on Marxism. The Marxist Educational Press continued to function and published a journal, Nature, Society, and Thought. I worked on the editorial staff and translated abstracts into French.

Opposing War and Racism, Locally and Globally: A Family Tradition

In the early 70s when Kieran was a baby, I worked on the boycott of grapes, lettuces and gallo wine for the United Farm Workers. There was a chain of grocery stores in Minneapolis called Red Owl. We had a number of what were called secondary boycotts, asking people not to shop where non-union grapes and lettuce were sold. We would stand outside the Red Owl, hand out leaflets and chant. Kieran’s first full sentence was, “Don’t Buy Lettuce, Don’t Buy Grapes.”

Jim and I got involved in local school politics in the 1970s. The head of the Minneapolis Public Schools had proposed shutting down Central High School, a magnet school in a poor neighborhood in South Minneapolis and changing a progressive grade school which my son attended into a fundamentalist school. We worked with neighbors and the Minneapolis NAACP to block the closure and the changes. We lost, but we made many allies in the African-American community.

In the 1980s I was involved in opposing US war in Central America. By then Kieran was also a real leader in some of those demonstrations, working with Anti Racist Action. I and both my kids got involved in anti- police brutality work.

My daughter Katrina was a sophmore in high school in 1992, when she began working with Anti-Racist Action as a police witness. They would go downtown every Saturday night, and follow police cars.. She got arrested several times. At that same time, I represented WAMM in a coalition for Police Accountability. We managed to achieve a Civilian Review Board of the police, but our demands for subpoena power and recommendations for police discipline were rejected.

Kieran got arrested for anti war work. Once he was beaten very badly by the police. He was never charged with anything. I picked him up and took him to HCMC to have photos taken and have him treated. We filed a complaint. It never went anywhere. That was very hard.

Around 1993, Kieran was arrested for hitting a Nazi on the Uof M campus. The Nazis had been attacking a group of anti-white supremacist demonstrators. Kieran was on security. He was on the bridge between Ford Hall and Coffman as the Nazis marched across. One of them had brass knuckles. Kieran hit him with a flashlight. The police first arrested the Nazi, but a couple days later let him go and arrested Kieran.

Kieran faced two felony counts and the possibility of decades in jail. Keith Ellison represented him. Ellison was head of the Legal Aid Society at the time. The trial went on forever because the prosecution wanted the Minnesota Daily to turn over any unpublished photos of the incident.

The case went to the Minnesota Supreme Court. The Daily refused to hand over photos. The Editor, who was a woman, spent the night in jail.

The next day the jury acquitted Kieran. The head of the jury was a WWII veteran who said he understood what Nazism was. The judge was Pamela Alexander. After she thanked the jury she turned to the prosecution and said, “Why did you ever do this? Why did you waste our time?” Mark Freeman was the DA at the time. He wrote an opinion piece for the Star Tribune justifying his prosecution of the case.

Jim and I worked really hard, along with other peace activists, to elect Keith Ellison to Congress, when he was running to fill Martin Sabo’s seat. Keith was the first African-American representative from Minnesota and the first Muslim to be elected to Congress. After that election, he was easily re-elected, but in 2006, it was a wide open primary. I am very proud of our work on that campaign.

Katrina is still doing work against police brutality and racism. She is a muralist. She works with a group of community artists organizing mural projects, bringing together neighbors to decide how they want to be represented. They recently finished a mural on Franklin Avenue. A replica was displayed at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Katrina has also done murals in Bemidji and Red Wing, doing what so many of us, after the 2016 election, said we should do–getting out of our South Minneapolis bubble and connecting with people across urban/rural divides.

Kieran works for a phone company and is active in the Communication Workers Union (CWA). He also works at Seward Co-op. He still demonstrates against police brutality and police killings, continues to organize against neo-Nazis and white supremacists, and supports the annual Twin Cities’ march on May Day for Immigrant rights. He and his wife have two teenage sons. My wonderful grandsons are also very active in protesting police brutality and our current immigration policies and practices.

Jim died in April, 2015. I really miss him, his analysis, his calming presence, his songs.

Trials and Tribulations of an Adjunct at the University of Minnesota

When I first joined the Party, I was not out at work. I certainly was open about my opposition to the war and my activism in the anti-war movement. The Department never directly told me to stop my activism. Sometimes they would tell me they wanted me to “develop my papers more” and that I was spending “too much time on other things.”

Before I finished my dissertation I taught at General College for four years in this really great program the legislature had approved in which African American, Chicano and Native American students took courses culturally relevant courses together in General College. I was their writing instructor, helping them with history and literature papers assigned in other courses. That was a great experience. Unfortunately, (years after I left), the U closed General College, and with it so many excellent, accessible programs.

Once I had my Ph.D. I taught at Ripon College for a while, but I couldn’t stand being in a little town. It was like being back in Iowa. I came back and taught French at the MCC (now MCTC). I loved being in the union and enjoyed the students, but they didn’t like having to pay me more because I had a Ph.D. They let me go before I got seniority.

I came back to the U of M and became an adjunct–(the U uses the term Lecturer)–in the French Department–did that until spring 2019.

It was a constant struggle. I was discouraged from doing research on things the French Department did not already teach, like Algerian or Haitian literature. One particular chair accused me of teaching too many upper division courses, so I went to the Women’s Studies Department to teach graduate courses on post colonial literature.

My last years, I served as faculty in the short-lived Master of Liberal Arts program, where students designed their own Master’s degrees. I taught a few content courses, the final project seminar, and oversaw their theses. This Spring the U closed the program. The U admin. claimed the Department wasn’t making enough money. At the same time they were hiring more top administrators and elevating their pay. The Master of Liberal Arts was too radical an idea, giving students way too much autonomy and Department administrators not enough.

Solidarity with Haiti

I took my first trip to Haiti in 1998 with IFCO Pastors For Peace. For years I had been supporting Pastors’ annual caravan to Cuba, bringing material aid in defiance of the US embargo, collecting goods and organizing educationals.

Pastor’s for Peace head Lucius Walker had this idea to go to Haiti to investigate US complicity in the the first coup that ousted President Aristide. I was invited to be the French interpreter along with a young Haitian who spoke Creole. There were fewer than ten of us, mostly from New York.

We traveled the nation in a van, starting in Port au Prince, traveling to Gonaives, where some of the most brutal repression took place during the 1992 coup that took out Aristide, then to Cap-Haitien and Milot. We met with church groups, unions, and farmer organizations and a Catholic priest in Gonaives who wrote a book about the violence in during the Coup. We tried to find out the role the US had played in 1992. We met with U.S.A.I.D. officials and demanded they release the documents. They said, “We destroyed that documentation.” One official admitted US involvement. He said, “You will never be able to prove it.”

We didn’t meet with women’s groups. When I started to go back on my own, that was my focus. In 1999, Ruben Joanem and I took a group of students to Haiti for two months as part of the U of M’s two year SPAN program. Most of them knew French. We all took Creole language lessons at the Resource Center of the Americas before we went, from a Haitian American Minneapolis public school teacher. The students loved Creole because you don’t have conjugate verbs. The way to signify past or present is by an adverb.

There was very little work on Haiti being done at the U of M during those years. I kept going back to meet with women’s groups. I’d stay at an orphanage that rented rooms. The director of the orphanage was politically connected and would introduce me to women who were engaged in political activism. I started writing papers about their work and about Haitian authors.

The Haiti Justice Committee—formed in the 1980s –had gone dormant after Duvalier was ousted. I helped revive it in the 1990s and have been speaking in solidarity with Haiti ever since.

Peace Activism 1990-Present

I got involved with Women Against Military Madness at its inception in the early 1980s, representing the organization in the Coalition for Police Accountability. WAMM co-Director Lucia Wilkes asked me to serve on the Board when I was the head of the Communist Party in Minnesota and its most visible member. I said it wouldn’t be a good idea for me to be on the Board of a mass peace organization when I was in the leadership position of a political party.

In the 1990s, after I left the Party, I did join the Board, serving as Co-chair twice. The organization was a political home for me, especially with the onset of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. I did my Haiti Justice work, and participated in actions to oppose endless wars, attending weekly vigils on the Lake Street Bridge every Wednesday for a decade.

In 2011 there was a split in WAMM over Syria in particular, and generally over the ability of the organization to embrace several positions on a foreign policy in a mass united front tent—as long as we came together to oppose US intervention. I couldn’t agree with the position on Syria put forward in the newsletter and at organizational forums. I and others who disagreed were not allowed to contribute an alternative view. We tried mediation, but that fell apart.

That caused me to leave another group that had been a personal and political home for me. It was very difficult. I do see some of my old comrades in WAMM. In all my political work I have always been someone who tried to bring people together.

I know I don’t have any more energy in my life for another internal battle. It is so counterproductive and sad. We have real battles: militarism, homelessness, education, police brutality, immigrant rights.

Today I work with the Minnesota Peace Project. MPP started about 15 years ago by Roxanne Abbas and Mary Hines. I have been involved for about six years. We are divided into teams according to Congressional District, to lobby Minnesota representatives on a peace and justice agenda. Our focus is on foreign policy; to cut the military budget, to keep the US from intervening, to end US support for wars, to abolish nuclear weapons. We are working on Israel/Palestine. After much debate, we did endorse BDS. Barry Cohen of Jewish Voice For Peace Twin Cities, who all works with MPP, was the main proponent.

We make clear our big agenda while working on intermediary measures. One small step toward BDS that we are supporting was initiated by Congresswoman Betty McCullum, to make aid to Israel contingent on Israel ending the practice of arresting, detaining, and imprisoning children.

I worked hard to end the war in Yemen, to get the Iran Nuclear deal passed, advancements that Trump reversed. Right now, the National Defense Authorization Act is under negotiation. We are working to repeal the Authorization Act that Bush used to go to war with Afghanistan and Iraq in 2001 and 2002. We are also working to restore aid to UNRWA.

We did issue a statement on Venezuela after much discussion. Because of that, I was able to interest MPP in taking on immigration, which first appeared to some like veering from our foreign policy mission. I did an educational in which I showed the foreign policy connection. I also argued that immigration is where young people are engaged. It is a door to engaging them in foreign policy.

This year I worked with Minnesota Caravan Solidarity on immigration issues. We worked on getting St. Paul and the whole state of Minnesota to be sanctuary city/ state. We are supporting the efforts of my State Representative Aisha Gomez, who is working on outlawing the private detention centers in Minnesota. I attended the excellent symposium that Ilhan Omar had in August on immigration detention.

Everything is connected. The situation in Haiti is intimately tied to what is going on in Venezuela. Under Hugo Chavez, Venezuela provided oil to Haiti and refunded the cost to support social projects. All that money from Venezuela — a huge purse — has disappeared. When Maduro had to stop giving the oil to Haiti due to the US embargo and falling prices, the Haitian government imposed rationing. The current turmoil in Haiti is directly related to U.S. role in Venezuela.

In early November I spoke about Haiti on a panel organized by a group of graduate students at the U, on causes of these mass rebellions in Lebanon, Chile and Haiti. We drew many connections.

It is good work. I am with the team assigned to Senator Tina Smith. I think she is a good-hearted person. Smith showed up for DACA youth and refused to leave, (though her staff wanted her to move on), until every youth had spoken. I think she may be the only elected representative who previously worked at Planned Parenthood. I believe our work with her will be easier when she finally has a six-year term and can stop campaigning. But I think she thinks foreign policy is not a winning issue.

MPP is also beginning to focus on the connection between militarism and climate change. The US military is a major contributor to the climate crisis. We guilt each other when we need to get on a plane to see a dying family member, though getting those bombers out of the sky, and ending chemical warfare would do far more to address climate change. It is time to make those connections and build a really broad movement for peace and justice and to save the planet.

The lessons I have learned from all this are: be open about your politics, your beliefs, your vision for the future. Always tell the truth; and listen to younger voices.

The Murder of George Floyd and Minneapolis Uprising

Note: the above includes whole segments from April’s written recollection of her years in the Communist Party.

Minneapolis Interview Project Explained.