There is a new group, Midwest Mixed, a space for people of mixed race. I taught a writing class with them this past spring. The participants were younger. They were taken by the fact that I was using books that were no longer in print. I was taken by the fact that they didn’t know about the people who forged a path for them.

—Sherry Quan Lee

I am the youngest of five children. My Dad left in 1953, when I was five. I don’t remember when he lived with us. Mine was one of the few families in the neighborhood that had a divorce.

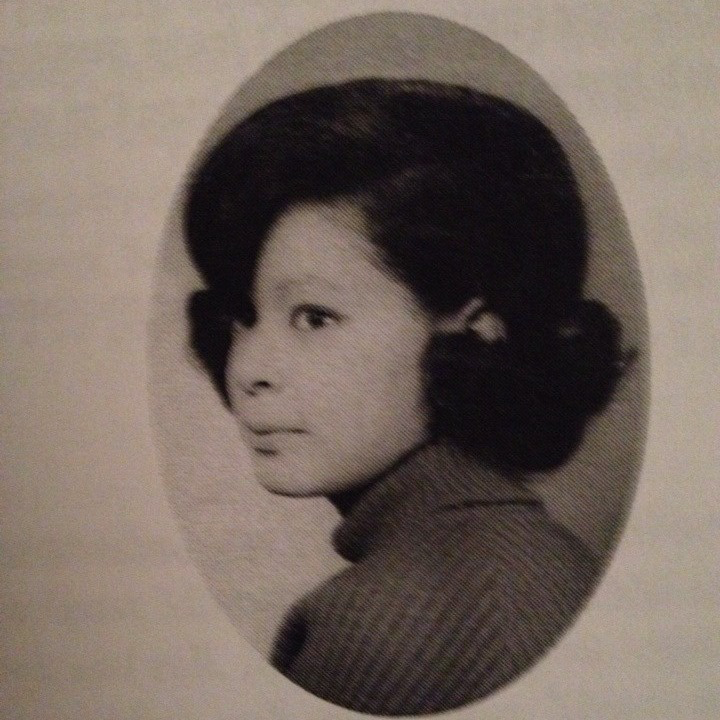

I was raised in the Standish neighborhood, or what I call, South Scandinavian Minneapolis. My father is Chinese, my mother is Black. They are both deceased. I always wondered how they were able to buy the house I grew up in, with all the racist real estate practices and neighborhood covenants. I don’t know if they had the same restrictions against Asians as they did for African Americans. I wonder if that was a part of why my mother tried to pass as White.

Passing as White

I was very naive growing up. It took me years to understand why my mother was trying to protect us by passing. Some of her family lived in North Minneapolis. She gave up public contact with them in order to pass. We took a bus to the northside to visit my aunt a few times. If they visited us, it was at night so the neighbors couldn’t see that they were Black.

What did it mean to grow up thinking you are white? I was indoctrinated. We had a Black cookie jar — the one with the Aunt Jemima-like figure. I read racist books. We frequented the Roosevelt Library. My mother read to us. All of the authors were white, and some of our favorites were explicitly racist, like Epaminondas and his Auntie and Little Black Sambo. I read those two books over and over.

I read Epaminondas to my kids! They learned how to read on that racist book, memorizing every word. It is the story that many cultures have, of the foolish one who messes up everything they do, but the illustrations send the message that Black people are merely caricatures.

White Church

In fourth grade my Lutheran Church Sunday school teacher asked us, “A Black family wants to join the church. Should we let them in?” I remember thinking, “I might be Black, and I’m already here…” They didn’t let them be members. Today that building houses an Oromo Church. The whole neighborhood has changed.

I went to church because I wanted to. My mother did not go to the Church. She was faithful to Unity, where she sent money in exchange for prayers. At one point the congregation raised money to help us out, but we never received the money. My mother felt ashamed and wanted me to quit attending, but I kept going. It meant too much to me. I told myself “I don’t have a dad, so God is my father.” That idea helped get me through childhood and puberty.

Identity in High School

In high school I was a wallflower. I did join the creative writing club because I had a crush on a member. Writing was my favorite subject. Because I was unknowingly passing for White, I didn’t know what was going on — the sit-ins at Woolworths, the civil rights and Black power movements. What I remember is my mom not letting us go to football games in North Minneapolis because “There might be a race riot.”

When I went to a high school reunion, a former classmate said to me, “It must have been difficult for you, being the only Asian.” That amazed me. I was confused about my own identity then. I thought, how did he know I was Asian? Recently, I connected with a friend from high school who lived down the block from us. She told me, “We knew you weren’t white. Some thought you were Chinese, some thought you were Black. We all knew you weren’t white, but when you joined the Brownies, we knew you were OK.”

Becoming Conscious

I was lucky to be seeking knowledge and understanding when the feminist and Black liberation movements were happening.

My feminist awakening–though I didn’t realize it at the time–was when I first understood that the church was devoted to a patriarchal hierarchy. It was on Good Friday, when I was in 9th or 10th grade. The pastor asked for volunteers to talk about the Last Seven Words of Christ on the Cross. My friend and I volunteered, but they wouldn’t let us because we were women.

That forever changed my relationship with the Church. I still believe in God, prayer, miracles-and angels, but the church I imagine has no walls. There is only one emphasis: Love.

After I left home at nineteen, I made a point of connecting with my mother’s Black family. I became very close to my Aunt who lived in North Minneapolis. She was a writer and activist. Today I am close to her son and his daughter–my cousins. They both support my writing on family and identity.

I did not start exploring my racial identity through writing until my early 30s, when I went to North Hennepin Community College and started taking English courses. One teacher told me I was too late: ‘Writing about race is no longer trendy.’

Luckily I had Sandra Stanley for a Women in Literature class. The department later cancelled her course, claiming she was too “biased.” For me hers was the best class ever. For one assignment we were supposed to go to a bookstore and see what kinds of books were on the shelves. I went to Amazon Bookstore (the feminist flagship independent bookstore in Minneapolis). Even there, I could find no books about me. So I went home and wrote. And wrote. I kept writing, to figure out who I was, to write myself into literature. I am still doing that.

I took my writing to my poetry teacher at North Hennepin. The writing I did in that class became the basis of my first poetry chapbook, A Little Mixed Up. At the publication reading Bruce Henry, (who still performs in Twin City venues like the Dakota), sang Black Cowboy.

Mentors, Organizations and Grassroots Publications

There were so few mentors for writers of color in the Twin Cities back then. I was fortunate to meet Carolyn Holbrook and David Mura.

Carolyn had created SASE the Write Place to address the fact that The Loft—where she was the Director for five years—was not diverse at that time. People of color needed a place to write, read, and publish their work. SASE had readings almost every night at places all over the Twin Cities. I curated events at Black Bear Crossing and Patrick’s Cabaret. The curators would choose people in the neighborhood to read. They would get paid $25 a night, which was unheard of–for writers to get paid to read their work. In 2006, SASE merged with Intermedia Arts, which worked for a time, until they decided to drop it. Now Intermedia Arts is gone too.

Carolyn was deeply committed to mentoring, and her influence was far reaching. I thanked her recently for including my work when she edited the Drum Voices Review in 2000. She reminded me that I nominated her for the Kay Sexton Award, and she became the first person of color to win that award. Mentorship moves back and forth.

David Mura introduced me to the Asian American Renaissance, a grassroots pan-Asian Arts movement in the mid 1990s. AAR was an umbrella for Asian artists and arts organizations. It was a revelation for me, to connect with the vast world of Asian diaspora and dancers, performers, painters, as well as writers.

I was the first Black (and first Chinese) student to graduate from the U’s MFA program. There were no faculty of color in the UM Creative Writing program. They brought David Mura in for one semester. One day when I was in his class, he handed me a note saying Asian American Renaissance was recruiting people for their Writer’s BLOC program. Writers were mentored by David and other nationally-known Asian writers. In turn, we mentored young writers in schools and other venues.

Working and volunteering for Asian American Renaissance, I met colleagues and community activists including Marlina Gonzalez, Charissa Uemura, Elsa Batica, Rose Chu, Sandy Agustin, and Vidhya Shankar. It became a home, a family. We put out a journal once a year. I suggested we do a book once a year. Mine was the first book: Chinese Blackbird.

Soon after AAR went belly up. Partly it was finances, but partly it was a measure of the success of the group. Organizations it nurtured, like Theater Mu, were having great success. Those involved still get together and talk about reconvening, but we are all busy doing our art.

Over the years, writers of color began to emerge. The Loft began having “Inroads” programs for writers of color. I was accepted into David Mura’s workshop and later I taught it. Sun Young Shin, the poet who edited the popular volume on race in Minnesota: Good Time For the Truth, told me “You were the first Asian American women who mentored and encouraged me as a writer.”

I was a groupie of Poetry for the People, which came together in the 1980s. Roy McBride, Tim Young, Susu Jeffrey. They did stuff at Whittier. They would do an International Women’s Day reading every year. Eventually I did readings with them. The group influenced my view of the Twin Cities writing community beyond Guild Press.

My visibility as a writer began with Guild Press. It played an essential role as a publication of unsung works, especially for writers of color. However, it became a #Metoo situation for me and possibly others.

In addition to Guild Press, publications like Colors provided spaces for writers of color.

In the 1990s I was a contributor to the Minnesota Daily. One of my Daily essays was a personal/political exposé on sexual assault in education and the workplace, in response to the Clarence Thomas hearings. They weren’t going to publish it, even though I did not name names. Eventually they did. #Metoo is not new.

When I was at the U, they brought Nikki Giovanni for a semester. While she was here she turned fifty. I took a chance and organized a surprise birthday party for her at the Riverview Supper Club, a Black-owned venue that closed in 2000. Many people came and read their works.

The Power of Words

When I graduated with an MFA from the U, I thought — what now? Carolyn was looking for community instructors for SASE. We set up a class at a coffee shop at 57th and Chicago Ave. The group loved it so much they signed up as a group to take it again. Sandy Newbauer, and Lori- Young Williams were in that class. Today they are writing peers.

You never know how your experience will heal others. Pamela Fletcher at St. Kates asked me to come visit her class after assigning my, How to Write a Suicide Note. I was really scared about talking suicide with college students. Dr. Fletcher told me not to worry about it. She had also assigned Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf. Most every one in the room had experience with someone who committed or attempted suicide.

In Love Imagined I wrote:

I detest labels, yet sometimes we are forced to self -identify. I have used biracial, mixed race, African American, Black, Chinese, Chinese and Black, as well as lesbian, bisexual–fem; as well as mother, wife, divorced, single … My identity is a wealth of adjectives and nouns claiming who I am.

It is amazing when my unique identity resonates with the journeys of others. One of the best reviews I ever got was in the lesbian feminist publication Sinister Wisdom. Julie R. Enzer asked rhetorically, “Who will be revered as in the caliber of Audre Loudre and June Jordan?” She mentioned me, and Chinese Blackbird.

Writing as a Community Resource

There is a new group, Midwest Mixed, a space for people of mixed race. I taught a writing class with them this past Spring. The participants were younger. They were taken by the fact that I was using books that were no longer in print. I was taken by the fact that they didn’t know about the people who forged a path for them.

I told them that decades earlier we had mixed-race gatherings at a South Minneapolis Church, and began speaking out together. In 1982, I edited a chapbook, Chromosomes and Genes, highlighting mixed-race people in the Twin Cities. Included were: Nancy Peterson and Chester McCoy, Barb and Rich Bergeron, David Lawrence Grant and Celeste Grant. I shared my own chapbook: A Little Mixed Up, with Midwest Mixed. I told them about Elroy Stock, a racial purist from Woodbury, who clipped newspaper articles about mixed race people and sent us terrorizing anonymous letters. It was years before they caught him.

I love that these young people are doing the work now. It is important that they know what went on before them.

I was at Ancestor Energy bookstore when my memoir, Love Imagined came out. A Mexican woman told me, “That is my story too! My mother didn’t want anyone to know we were Mexican.” Telling my story has given others permission to write theirs.

Legacies

Long ago, I wrote an article in the Daily about AIDS. A professor told their students they needed to read it.

In 2009 students of color at the U of M Dance program were being silenced by the department. They used the writings of bells hooks, myself and others, put our words on the walls. They kept getting taken down. Sometimes we don’t know how we influence people. We need to know that we are worthwhile because we may never know the effect we have had on someone. The important thing is to just keep doing what we are doing.

I wrote and performed a play with Lori Young-Williams called Chinese Black White women Got the Beat in 2006. Soon after Lori and I taught classes at various venues in Mankato, Moorhead, and the Twin Cities. The refugenius Saymoukda Vongsay took our workshop. And Kandace Creel Falcón who ended up teaching at Moorhead. Both of them wrote essays for my anthology, How Dare We! Write: A Multicultural Creative Writing Discourse.

How Dare We! reflects the need for writers of color to pass on wisdom and courage to write, critique the dominant academic pedagogy, and crash the gates. All of the writers, even if they reside out of state, have connections to Minnesota. The anthology is my most important work, going beyond me as a singular subject, focused on the collective we.

I have had the honor of teaching creative writing at Metro State. Tou SaiKo Lee is one of those students. I am working with him as a writing coach as he completes his memoir focused on his grandmother, with whom he had a spoken word group, Fresh Traditions.

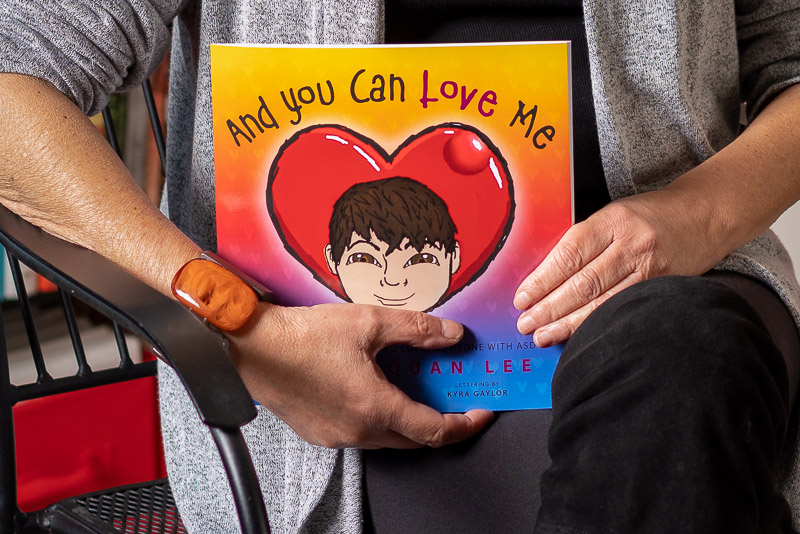

My most recent book is a children’s book, And You Can Love Me, A Story for Everyone Who Loves Someone with ASD, for my grandson who is autistic. This is the first book I wrote because I wanted to, not because I had to. The book evolved with the mentorship of Allison McGee.

When I started writing and becoming politically conscious, I was older than most of the people I was working with. It didn’t seem to matter then. The age difference mattered more later, when I became a grandma and they were just beginning to have kids. It is easy to get isolated.

Recently a friend passed. I had known him since I was 19. I just happened to have coffee with him a couple weeks before he passed. It made me realize how important it is to stay connected to people and not let distance be a deterrence.

In search for my own identity, for visibility beyond a White persona, writing became a path that helped me discover who I am. I had mentors who guided my way. Acknowledging the presence of mentors is the backbone of activism, of telling untold history, of story.

One of my favorite quotes is from Giovanni’s poem, “When I Die,”

/and if ever i touched a life i hope that life knows

that i know that touching was and still is and will always

be the true

revolution.

Sherry’s Books are available here

#Minneapolis #Minneapolisinterviewproject #Sherryquanlee