If Minneapolis was a character in a play, it would be that best friend your other friends wonder why you hang with. You stay with him because there is something enduringly endearing about him, even though he disappoints. He has a good side that outweighs the bad. He’s dopey and dumb, but sweet and well-intentioned.

—David Lawrence Grant

North Carolina Tidewater Roots

I grew up in DC, and loved Washington, but most days, if you ask me, I say North Carolina is where I’m from. I was born in Rocky Mount— east of Raleigh. The name of the town refers to an odd rock formation in the middle of the Tar River. It is where my father’s people are from. I spent my summers there, with my grandparents.

The North Carolina tidewater culture is a major part of my interior landscape– grabbing long poles with my grandmother and my Aunties, hunting for crabs, filling a bushel basket, adding fresh fish roe to our eggs and grits in the morning, or fresh oysters. Heading home from the ocean, we’d buy a large jar of honey to put on our morning toast.

The women in our family were more into that stuff than the men. My grandfather was a sweet guy, but not much involved with young children. The best and longest interaction we ever had was the summer I turned eighteen. My grandma had just died. I went to visit him. The house was a very sad place– like viewing the recently deceased: you know the body is not the person it once was.

I had taken the train. It arrived at 3:00 am. I had a general sense of where my grandparents’ house was, so I started walking. A cab driver stopped to see if I needed a ride. I didn’t have any money, but when he found out I was visiting my grandfather, he said, “You ain’t gotta pay nothing. Get in the cab son.”

Grandpa had been waiting since I was born for me to be old enough to share a bottle of corn liquor with him. When I walked in, there was a quart of moonshine on the kitchen table, made by some neighbor. He swore it was the best I’d ever have in my life — and he was right. We drank and talked until dawn. He wanted to see if I could hold my liquor and I passed the test — I wasn’t on the floor when the bottle was empty, so I measured up to the standards of the men in the family. At daybreak we made a tidewater breakfast. There was still a little bit of the grainy thick stuff at the bottom of the honey jar for us to spread on our toast. It was a magic morning.

Theater Child in Washington DC

As a little boy, I was making money as an actor with the National Children’s Theatre in DC. Got my social security card early. From age 10-12, I had a regular gig on the CBS TV show, Lamp Unto my Feet, put on by the National Council of Christians and Jews. It was on every Sunday Morning. I was also part of a public radio show where kids got to interview luminaries. I interviewed Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas. I wanted to interview Thurgood Marshall — but it was still thrilling. Douglas had just written a book about nature and mountain climbing, and that is what we talked about. I did voice work for the Spanish and Portuguese Voice of America show. And I was in a children’s choir. I had a great soprano as a little boy. In 1961 I played a street urchin in the Metropolitan Opera’s Carmen.

My mother, Alice W. Grant, was a professor at Howard University. She taught creative writing, ESL and African Studies. Our house was always full of her students. One or two were usually living with us. My mother was not a good cook. I learned how to cook African and Asian food from the foreign students.

It was a very political house. The Ghanaian writer Ayi Kwei Armah who wrote The Beautyful Ones Are not Yet Born lived with us. Eduardo Mondlane, founder of Frelimo — the Mozambique revolutionary movement against Portuguese colonialism — was my mother’s friend. A young Vietnamese student, who I loved, lived with us for a year. She was having a hard time, watching the growing war in her country from afar. Eventually she left to fight with the Viet Cong.

My mother had an office overlooking Founders Hall that she shared with Toni Morrison.

Morrison influenced my young life. She shaped and critiqued my reading list. If she heard a new word slip out of my mouth she’d challenge me. “Do you even know what that word means, little boy? Let me hear you use it in a sentence.” Somewhere in mother’s things is a nineteen page story draft of the Bluest Eye with my mother’s handwritten note: “Oh Toni, this is wonderful — this should become a novel.”

While my mother had a great career at Howard, my father’s job at the labor department was not fulfilling. He was just a warm body. He and I acted in a production of Brigadoon put on by American Light Opera Company, which was full of CIA and State Department operatives. His friends in the theater recruited him to apply for a foreign service position in Africa. They told him he would be able to participate in reshaping US policy, which intrigued him. He took the exam and got the highest grade, but he couldn’t pass the security test. During the application process we had people sitting in unmarked cars checking out the people who came and went in our house. That spooked my parents. It became clear he would never be able to move the needle from the inside.

Getting To Minneapolis

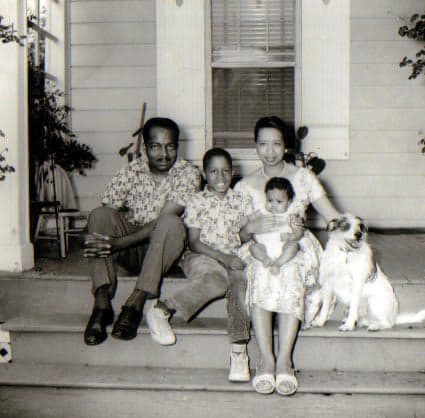

My father, Samuel H. Grant, got a job as a placement officer at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. My mother was able to get a similar position at Lincoln, teaching the large population of African Students. While helping students get jobs with American industries, my father got recruited himself, by Cargill. In the summer of 1969, we moved to Minneapolis.

My parents bought a house in southwest Minneapolis near Minnehaha creek, not far from where I live now. When my grandfather came to visit, he got a cab from the airport and gave them the address. The cabby said, “Sorry sir, but that address can’t be right. There’s no colored living over there.” He was right. We were the only ones. He was amazed when he pulled the cab to the curb and my father came out to greet his Dad.

In the fall I started college at Oberlin– a liberal arts institution in a small Ohio town. I did an urban semester in Philadelphia, teaching film and photography to junior high kids, and fell in love with my job. I worked out a deal with Antioch College– part of a consortium with Oberlin– to get credit and stay in Philly.

I had developed some close friendships in Minneapolis and had begun to think of the city as my home, so even though my parents had moved on, I came back to Minneapolis when I graduated in 1973.

A Writer for Grassroots Recovery Groups

I identified as a writer since I was ten — an idea nurtured in that office at Howard University. In Philly my nebulous plan for a career was to be the communications person for non-profits I cared about, to tell their story and attract dollars. I created a niche for myself doing just that. I wrote radio and TV PSA’s and read them on KFAI and KMOJ. (We are so blessed with community radio in Minneapolis!) I had friends in WCCO and KMSP who let me come in at odd hours and use their technology; help me tighten my work.

Patrick and Lorraine Teel had started a chemical dependency therapeutic community. At first they were putting people up in their homes until they could find work and live on their own. Eventually they got the funds to open Eden House. I began working with them.

Chemical dependency programs were burgeoning in Minneapolis in the ’70s. In addition to the big organizations like Johnson Institute and Hazelden, there were grassroots organizations, like Eden House, dealing with especially tough issues serving guys experiencing the trifecta: incarceration, addiction, and mental illness. I met my wife Celeste, through this work. She volunteered with Pharm House, another group that grew from the streets focused on youth.

Eden House was on 224 Ridgewood Avenue — an address that no longer exists, in the neighborhood not far south of Loring Park. It was an amazing program — still is — now run by Dan Cain, who I met back then, when he was recently out of prison. I wish the long term 90-120- day residential model we pioneered would have prevailed. The funding from city, county, and state, only supports much shorter stays –not enough.

I did that until Peter Bell hired me to work with the Institute on Black Chemical Abuse. I did drug abuse prevention at the regional state and national level, wrote a newsletter with a national circulation, wrote curriculum and put on workshops using that curriculum.

Becoming a Screenwriter

In the late 1980s, I took a screenwriting course at Film in the Cities and decided that is what I needed to do. At the same time my wife was starting to think about law school. I wanted to make her pathway easier. I thought if I took my writing skills into the profit sector, I could make more money and have more time to work on my screen writing. I went through a grueling four-part interview process for a copywriter position at a major advertising firm. The boss told me, “The hiring committee wants you, but I’m not going to hire you. I looked at your MMPI and I know things about you, maybe you don’t know yourself. I know you would do great work for me, but you would be the person at the water cooler stirring people up, empathizing, making trouble for me. You told me about books and periodicals you read — impressive — but you didn’t mention Advertising Age. You will always have some damn novel or screenplay in your top drawer. That is what you ought to go do.”

I got a similar message from the Director who took over from Peter Bell at Institute for Black Chemical Abuse. We had it out when she found me working on a screenplay at the office at midnight. She offered me a compromise. I could do the recovery workshops I had developed for the organization, on my own, for profit. That untethered me, allowed me to invest in my writing.

I have a note on my desk that says ” A writer is someone for whom writing is harder than it is for other people.” I look at it at least once a day.

They say you need to write a couple million words before you have something you can stand by. After a couple years I wrote something that was good enough. I was a winner in KTCA 1989 contest for short screenplays. The Screenplay Project: Four Shorts collectively won a regional Emmy. Mine was an eighteen minute script. It starred Izzy Monk, who was a Guthrie team member, Louis Alemayehu’s eleven year old daughter Anika, Fay Price , and Terry Bellamy. It was about a woman who remembers abusive aspects of her relationship with her mother, while her mother is ill. It was about finding ways to salvage what is good from a situation that hurt you. It was called “The Things that Matter.” It was my first produced project that was purely drama.

Racial Inequalities in the Minnesota Judicial system 1993

In 1993 I was hired by Rosalie Wahl of the MN Supreme Court, to write up their findings on racial inequalities in the justice system. The report was shared with courts in Minnesota and other states. It was my job to make the findings understandable to people who were not lawyers. We looked at who gets arrested, who gets charged, who gets set free, what people get charged with, the issue of cash bail, jury selection, and sentencing, finding bias at every level. We delineated changes that could be made that would decrease racial bias in the system. A lot of states used it as a model.

I was invited to the 10th year anniversary of the report in 2003. People talked about how much work was left to be done, but they also took stock of what had been accomplished. It sparked conversations, and laid out a roadmap. Simply being involved in the project, helped judges and prosecutors develop a consciousness of their own biases.

Hollywood Screenwriting

In 1994 the NAACP had their national convention in Minneapolis. They had contests for youth: best science fair project, best architecture project, best essay and short fiction. I was recruited to judge films. There were four of us, including a Disney executive who was in town shooting Mighty Ducks. After four days of hanging out in a room together we became friends. She said, “Send me your best script.”

Hollywood script readers are really bright, overworked, underpaid, and therefore a surly bunch. They already hate you before they read page one. My Disney friend’s reader liked my script so my friend read it. She thought it was too Indie for Disney. She showed it to her friends at Touchstone. The passing around got me known. I landed a job as a screenwriter for a project with Def Pictures and got myself an agent. My children and wife ruled out moving to LA, which made it harder, but I had enough work to become a full-time writer. By 1994-95 I earned more from my writing than from my recovery workshops.

My script: The Cool Blue North is a little family drama.

The executives in LA Def Pictures, had a bet about whether the script was autobiographical. It was not. The main character is a composite of some of the guys I met in treatment. Over a ten year period we came close to getting that film done three times. Warner Bros wanted to morph it in an action movie. It almost turned into something I didn’t recognize.

The last time it had been placed with an Indie company we admired. They had a deal with Fox 2000, which was totally about it, until the people championing it, were not there anymore. I got ghosted, and figured that was it. But then I got a call a few months later.

“We are back on. We have a couple of A-list actors who want to do it. Can you make the family White?”

It was like the devil talking into my ear. We really needed the money. It would have been so easy to say yes. I said no.

A year ago, “Cool Blue North” was put back on the burner. My Hollywood advocate asked me to rework it. It still might have a life.

Twin Cities Theater Projects

In 2005 I collaborated with VocalEssence , Philipp Brunelle’s choir. They were spotlighting Gordon Parks for their Witness project. In addition to being a great writer and photographer, Parks was a composer. I got to write the program. What an amazing opportunity, to research his music.

That same year, the Minnesota History Theater had me come in and review all the winners of a competition of youth, writing about their neighborhoods. My task was to use their words to resurrect one of the History Theater’s popular shows called Inner-City Opera. We called the 2005 version Snapshots: Life in the City. I wrote the script. JD Steele wrote the music. We collaborated on 26 original songs for the show. That was about the most fun you can have.

In 2011 Mixed Blood Theater had me come in and do a similar project with members of the east African immigrant community. For a year I got to be the guest of honor as a group of immigrants, mostly women, bared their souls: here is what America is to me, here is what the camps were like, here is what I miss about home. We created a trilingual play: Khu Soo Dhawada Hafadeena — in Somali, Oromo and English.

Working on equity is in my blood, as it is for my brother, Sam Grant. One of my recent projects is the collaborative with other Minnesota Writers of Color, A Good Time for the Truth (2016), edited by Sun Yung Shin. The book, which has sold 25,000 copies and is the MN History Press’s best seller, is being used to inspire community conversations about race. Groups will read it and invite a number of us to come and steer the conversation to the next level. I’m doing about one of those conversations a month.

Ancestors

I am also in the book, Blues Vision: Writing from Black Minnesotans. My piece is about my experience –through DNA matching– of connecting to my lost family in Africa. I found cousins in Ghana, Sengal, Nigeria, and the Congo. I have written a book–yet unpublished–called, I Would Know You by Your Feet, about how we encounter each other across the diaspora, how we fashion something deep out of our connection with each other and what that says about our collective way forward.

There is a whole other book waiting for me to write it, about the White kin I have found.

A group of White amateur genealogists realized they were sitting on a treasure trove of information about Black families. They formed Beyond Kin to help Black amateur genealogists trace their ancestors. We hit a brick wall when we try to look beyond the 1870 census. On the 1850 and 1860 slave censuses we are listed only by age and gender. We have oral histories, but most are not accurate. Beyond Kin are sharing wills and mentions in family bibles that give us invaluable information like: ‘Our family sold your ancestor to a plantation owner in Mississippi in the 1840s.’

I found one woman in Virginia with whom I share an African ancestor, a man from the Congo who was a slave in the 1640s but by 1660 he was free and a landowner. The dozen other White relatives with whom I have been in touch, are related to me through a White person who once enslaved my ancestors.

The first reaction of many of these White relatives is to run in the opposite direction. Relationships with those who have been open to contact, have been interesting and rewarding. Our conversations have been fraught and complicated, but some have said, “Let’s talk reparations and what can we build with each other.” The one I am closest with lives in suburban Birmingham, Alabama. We have shared so much. Those are the most amazing conversations, rays of hope for me in this otherwise dark racial landscape.

Teaching Screenwriting

Right now I’m teaching screen-writing at Film North and at MN Prison Writing Workshop at Lino Lakes. I love it. One of my best students at Lino Lakes has signed up to take my current screen writing course at Film North. I haven’t seen him yet as a free man.

Independent Television Festival has just relocated to Duluth from New England. It is the Sundance of Television. My student from Lino has this great idea for a series that I am going to help him whip into shape called Catch and Release. about how the corrections system sets people up to fail.

A former student from Film North–another brother who was formerly incarcerated–wants to tell a story about the town he grew up in–East St. Louis, Illinois. What a hard place that is. We are making the city one of the characters in this drama. The working title is “Pick a Side.” I am partnering with him to get the pilot script written.

Writers like these, have all the potential in the world. Nothing makes me happier than to see people catch the fire.

Minneapolis Interview Project

#ToniMorrison #Goodtimeforthetruth #HowardU #Hazelden #MPD #PolicingMN