Do cops keep us safe? If you’re white or wealthy, for sure. Not if you’re poor. Not if you’re Black, Latinx or Indigenous. It’s disrespectful that we have to have this conversation over and over. More cops equals less Black people. Mayor Carter gave the city of St. Paul nine more police officers at a cost of $900,000. Look at what happened! More killings in 2019 than any other year! Abolish the Police.

— Jason Sole

Table of Contents

Born Into the War on Drugs and the Mass Incarceration Pipeline

I live dualities.

Born in Chicago, Southside, 1978, I was a child at the beginning of the War on Drugs. We never heard the term, “mass incarceration,” it was just our world. I could see that something wasn’t right; police pulling up on me everywhere I went, constantly asking me for ID when I was fifteen and didn’t have any; setting me up. I was smart in school, but I was upset at the world, upset at police, upset at classmates dying even before high school. My grades were amazing, but the level of trauma was just too much.

There was yellow tape everywhere in my neighborhood. I didn’t have a language for what was going on with us. If there were adults who had it, they kept it to themselves. Now we have the movie “13.” Not then. I always said to myself, “I’m going to figure this shit out for us.”

It took a lot of years, a lot of prison, getting shot, a lot of trauma before I figured it out. I’m grateful for the perspective I have, grateful for the grace, grateful to still be alive at 41. Most people in my neighborhood ended up dead, or in jail.

Teenage Parents

My mom and dad were teenagers when they became parents. Mom is smart. She worked at the post office for 28 years in downtown Chicago. I admire her, love her to death, but her love wasn’t enough to keep me from the streets. Still, I was always saying, “I’m not going to sell drugs forever.” I was reckless, but I was always smart enough to say, “This won’t be my life.”

I’ve still got father issues. He is addicted to heroin. My uncle — my mom’s brother —went to prison at twelve, got out when he was eighteen. He’d be in for seven, out for three, back in again. Prison broke him at an early age.

My family never left Chicago.

Gifted and Talented

In elementary school, I already experienced the duality, being smart but “bad.” I was bad because I was sad, though I couldn’t identify it at the time. We didn’t have social workers. If I felt like I was being attacked, I lashed out. Demanding to be treated right, I often went overboard. I couldn’t understand why I felt like I had to fight so hard. In retrospect, I realize I was in such a submissive role with my father that I didn’t have a voice at home. He was six foot three, I was a little kid. Whatever he said needed to be honored or there’d be consequences.

I went to Parkside Community Academy, a K-8 school. My sister LaToya is three years older than me. I had every teacher she had, so

I lived in her shadow. They’d say, “You LaToya’s brother?”, expecting me to be like her. But I was being socialized as a boy, so that didn’t make any sense to me. I’d say, “I’m Jason, not LaToya’s brother.” An activist long before it was formalized, I demanded they treat me with respect. Teachers liked me. I was the one who fucked up the relationship.

They put me in gifted and talented classes all through elementary school. I had the same teachers for first and second and another teacher for third and fourth grade. This provided necessary continuity in my life.

Mourning for Harold Washington

I had amazing teachers up until 7th grade. When Harold Washington, first Black mayor of Chicago died, my third grade teacher said, “Can we have a moment of silence.” I appreciated that. It wasn’t this “man-up” mentality I was used to but, “Let’s take a moment to be sad.”

My 7th grade teacher, Mrs. Keys, was mean to me years before I was in her class. She would say, “ I can’t wait until I have you. I’m going to scare you straight.” She would crack jokes about me and I’d crack jokes back. My sister had her for two years. Mom trusted that she knew what she was doing. She was the professional.

Forced into Remedial Education After 7th Grade

This is the Chicago public schools. Academically, the work was effortless for me. I didn’t realize how smart I was, but I noticed when I finished a test, the other students were still working. I was fucking bored! When I finished my work I’d ask to go to the restroom. I might go there or I might pull the fire alarm. Duality. They loved me most of the time, but I self-sabotaged.

Because I was acting out, my teachers recommended to my mom that I go to a different school for eighth grade. I went from gifted and talented classes to remedial classes. That shit didn’t make sense to me. I was a basketball player by 7th grade, good enough that people knew my name. They put me in a school that didn’t have a team! How could they put me in a school without a team? This is when Michael Jordan was playing. Every other school in Chicago had a team!

At Parkside I had been smart and bad. In the new school I was just bad. I got into a fight with a kid shortly after orientation; sixteen years old and in 8th grade. He was through with puberty and I thought he was a staff member. We fought and I got labeled a “bad kid.”

Paul Dunbar High School on Martin Luther King Drive

I went to Paul Lawrence Dunbar High School. Mr T, Jennifer Hudson and Lou Rawls are alumni. Dunbar wrote the poem, We wear the mask. We had a sense of pride, going to that school, but it was situated on 29th and King Drive.

Chris Rock has said, “Martin Luther King stood for nonviolence, but wherever you go in America if you’re on King Drive, there’s some violence going down.” The projects were adjacent to Dunbar High in two directions, across the street and behind the school. A lot of mental illness, a lot of drugs, guns. The police terrorized us, while all around us people were getting raped, experiencing gang violence.

In high school I engaged in it. I sold dope, smoked weed. I tried to figure out this money I made selling drugs, tried to use it to take care of people, help my sister go to prom, so I wouldn’t be like the men in my neighborhood: victims of the war on drugs, using, stuck. But at the end of the day, I was falling victim to the same shit I was trying to get away from.

In elementary school, my older sister had set a high standard, so teachers had expectations for me. She went to Lindblom High so I didn’t have that at Dunbar. Other than math, I never felt challenged.

Subtractive Schooling

Algebra never made sense to me. “X squared plus D equals Y?!” I had Miss Wren for Algebra II. I was on the basketball team, so I had to keep my grades up. I knew my friends on the team were not going to make it. I’d say to her, “If I’m not understanding this no-one else is. You have to explain it another way.” She came with the right heart and I knew she loved me, but she didn’t know how to teach Black kids. She gave me privilege because I played basketball. I didn’t want privilege. Some people took advantage of that if they played sports. My mom didn’t allow me to take those kinds of handouts. I’d say I’m gonna earn my grade, but I have to understand it.

At a young age, I was able to articulate and argue to prove a point. Often it got me into trouble. But I could not express emotions. I learned you had to hide those.

Family Examples

I had a great uncle, my mother’s uncle, Jonathon Walton, who left Chicago at a young age. He was a gay Black man. At age 16 he started college at Stanford, got a Ph.D from Princeton. His dissertation focused on the lives of slaves who went to Canada. I always knew who he was. He’d come around for holidays, always with a woman. He passed away when I was ten, of AIDS. Closeted in Chicago, at the University of Iowa he was an openly gay Black man working as a professor of Afro American Studies. They have a fellowship in his name. He was revered. His nickname in the Iowa NAACP was “Brotha.”

It was hard on my mom when he died. She was supposed to be the next one to make it for my family, but she got pregnant by my dad and that altered her course. She had regrets, as a teen mom. Knowing who my uncle was, helped me through those times when it was three o’clock in the morning and I was out smoking, making some money, and I got school at eight. I would say, “Hey, man I’m going to school in the morning. And you gotta go too.”

Doin Wrong, and a Whole Lotta Right

I had perfect attendance my freshman and junior years even though I got all this shit going on. When I got an invitation to hang out I’d say, “I’m doin’ my homework first. Then I’ll be over. I’m not about to fuck up these grades.”

I was doin’ wrong and a whole lotta right. My friends couldn’t believe my report cards. Mom wouldn’t have it any other way. I couldn’t come into the house with a D, like my friends. It was a gift and a curse. I had an uncle in prison and a genius in my family. I was battling both worlds, trying to be on the smart track, but the street’s got a way of pulling you in.

From the Top to the Bottom of My Teenage World

1994 was a bloody summer in my neighborhood, but I was doing well. I lettered in basketball and got to go to a camp for top players at a Community College in Kankakee Illinois, where the Bulls taught us skills. It was my first time out of the city.

A few kids were on their way to the NBA, with Mom and Dad making sure they did not get caught up in drugs. Most had nothing: dirt poor, trying to make it. I was in the middle, I had good grades, and drug money. It wasn’t legit, but it was change in my pocket for pizzas.

Returning home, I felt like I was on the top of the world, one of the top young ball players in Chicago. I felt like I worked hard and deserved that status.

While I was gone, my mom found drugs in my room. She worked third shift, so she had no idea I was in a gang. I could stay out until three in the morning. As long as my grades were tight she didn’t worry. She had three kids.

I was sixteen. She was sixteen when she gave birth and deferred her dreams. It broke her heart; took all of the trust away. She sent me to Waterloo, Iowa, to live with my aunt, to get myself together. I didn’t think it was the right solution but I loved my mom.

The gang is not a plaything. It had structure, with leaders and soldiers 500 deep in my neighborhood. They said if you’re leaving town, you have to get branded. I have a panther tattoo over it now, but if you look closely you can still see it.

Navigating Race in Waterloo, Iowa

Now I was dealing with racism. I never went to school with white people before, or any other race. I was Black and Muslim. The gang practiced Islam. I worshipped Allah. I was a tall Black boy with a gang tattoo on my arm, not eating pork, in Iowa.

Meeting Andre Wright helped. He gave me the lay of the land. Today, he is my friend and business partner. At sixteen he was my interpreter of Iowa culture. Everything was weird to me. I’d never seen open fields. The convenience store spelled Quick with a capital K. What’s up with that? I was over analytical.

The basketball coach walked up to me the first day of school and said, “Don’t bother coming to try-outs. Show up the first day of practice.” That made some kids hate me. I had to convince them—I don’t want your girlfriend, I have bigger stuff going on here. I’m homesick. Don’t bring me Iowa drama. I have my own drama.

Some things did not change. I had perfect attendance at school, and I smoked weed and kept a firearm in my car. Guys tried to come to school and get me. That caused friction in my aunt’s house. She just thought I was bad. I was getting body-slammed at home. My uncle was a Black farmer and truck driver. He still lives there. His life was something new. In Iowa I met Black kids with licenses and insurance, driving to school. Totally different from where I came from.

Some Great Teachers

Amongst all this, my French teacher Madam Griffith gave me some love I really needed. She wanted to send me to France the summer before my senior year. She believed in me. I couldn’t imagine staying in France with a family. Neither could my mom. And the price was $2000. It might have changed my trajectory. Just having Madam Griffith’s support meant something. Fast forward four years, when I was in prison, she wrote me a letter.

The first time Madam Griffith reached out to me was before my first basketball game. She pulled me aside and asked me if I was nervous. I told her basketball was effortless. One of my teammates, JJ Moses–he played eight years with the NFL, now he’s ambassador for the Houston Texans–sat next to me on the bus, and asked me the same thing. I said, “Trust me, I’m fine.” I wasn’t being cocky, I just knew the game, the mathematics of it, the science.

Madam Griffith said, “I’m bringing my husband and son to see you play.” When I went into the gym I saw her with her family. I didn’t have family there. It was hurtful seeing other people with their parents. To see her in the stands, cheering for me meant a lot. I performed — had a perfect game. Four for four from the free-throw line, two three pointers. My defense was immaculate. No errors, no turnovers. I finished the game with 15 points.

I had other great teachers in Waterloo. Ms. Boss wanted me to go into theater. I clowned in her class, put on radio and TV skits, doing the weather forecast with my friend Corey Taylor, whose mom had cancer. Having fun took our minds off our realities.

Standing Up to a Racist Coach

My coach was racist. Still is racist. He knew I was Muslim and didn’t eat pork, so he’d buy hot dogs and try to get me to eat them. He’d grab some guys by the collar. I let him know he couldn’t do that to me. My coach in Chicago could do that because I knew he loved us. When this Iowa coach tried to touch me, I told him I’d transfer to the rival school if he tried again.

I was a student of the game and it showed. If he had cared, he would have sent my numbers and videos out to colleges, advocated for me. My stats were good enough. I needed the help. He’s doing the same shit to the children of my teammates that he did to us.

I always felt justified in standing up for myself physically. If someone was going to try I was fighting back. But I didn’t bully. I didn’t hit girls. Maybe having a big sister made me see girls differently. When I was a senior, I went to prom with a college girl, not a junior I could take taken advantage of.

Homeless in Iowa

It didn’t work out with my aunt. She kicked me out. I stayed with friends; bunked in a college dorm for a night. Girls who were in school with me, their mothers and fathers would say, “Jason can stay here.” For them to trust me was amazing, but I had a hard time accepting favors from people. I always had enough respect to say, “I’ll stay one night, but 6AM, I’m out.” I wasn’t going to lounge around nobody’s house. My mom didn’t raise me to take advantage of anybody.

I’d go to the YMCA, practice a little bit. Then I knew I could take a shower. I had a name as a basketball player so I didn’t have to explain to them that I was homeless. It made sense to them that I needed a place to practice.

I was navigating a lot of trauma already, when I crashed my car into a school bus. I was a victim. It was a snow storm. Slid into the bus. Couldn’t stop. I had a license and insurance then. I got dropped off by the police, in front of the school. The whole day everybody asked me, “What’d they get you for?” I had to figure out how I was going to maneuver without a car. I didn’t need the gossip and speculations.

I had the credits to graduate December of my senior year. I stayed to play basketball. In January I lost my job as a telemarketer, selling people things they didn’t need. I was good at it, diligent, but I went to Chicago for a visit and didn’t tell them. The policy required them to fire me. At the same time I was selling marijuana.

Rejected By the Military

In February I committed to the military. Air Force. I passed the three physicals and the written; scored over 40 on it. Me and my buddy Corey Taylor had a boot camp date of August 27. I went home after graduation, waiting for the day.

In early August they called to say, “You can’t go.” I was like, “It’s in my yearbook. You gave me the stamp of approval and a boot camp date.” They said, “You had asthma as a child.”

We all had asthma in my neighborhood—I had a classmate that died in her sleep in 7th grade—but I grew out of it. I was an athlete. I didn’t use an inhaler in high school.

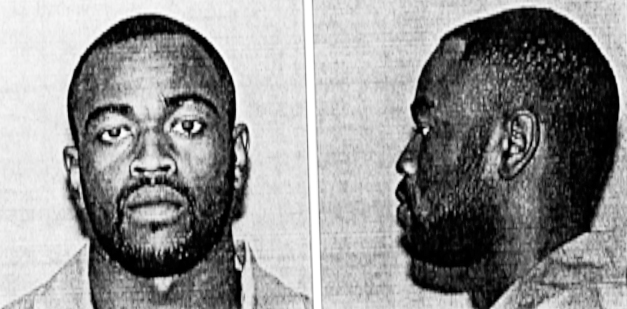

I checked out then, got immersed with the gang culture, moved with a pistol. I felt like a loser living in my mom’s basement. Photos of me then —-I’m ganged up. People are dying around me.

Getting to Minneapolis, and the Ramsey County Workhouse

A friend in Minneapolis who I knew through the gang, saw I was in a bad place. Wanting to help me, he invited me to come up to the Twin Cities. Police knew him and soon they knew me. I got caught with a firearm by the St. Paul police, after three months. They swarmed me from every direction. I went to jail.

I didn’t plan on staying in Minnesota, but now I had five years of probation. No-one cared about my basketball career or my GPA. Once I went in front of a judge, I was just a Black gang member with a gun. I spent a few months in the Ramsey County workhouse, picking up rocks in a unit with 40-50 people who’ve got mental illnesses, 8th grade reading levels, addiction, and severe trauma. They threw me in a unit with the Gangster Disciples. I was a Blackstone. If they were frustrated, if they didn’t get a phone call, they tried to take it out on me. I had just turned nineteen. I knew there was something wrong with this system, and I could see this was not where I should be.

Probation

When I got out, I had an unpredictable probation officer. Nice lady, but took her job very seriously. She was hot and cold with me. I didn’t know she was working with the police so closely. Some months we’d have a real conversation about my future, the next month she’d be gruff, make me pee in a cup.

The dualities continued. I was nice to my neighbors, and I was selling drugs, making 100,000 dollars. I never beat up an addict. The gang gave me a lot of leadership. Me going to jail put my whole team behind. High profile. In front of The Best Steak House in St Paul, I was shot, shattering my femur. I was hanging out in the clubs, but also playing basketball, trying to be close to Kevin Garnett, starting a rap label, How About It Productions. I was going to buy a barber college off of East 7th Street in St. Paul. Living in North Minneapolis, I was dropping kids off at school, encouraging basketball players, telling them not to sell drugs, buying them shoes. I had crazy parties at my house. No girl would be sexually assaulted at my parties.

I wanted to lift up my friends. The cops hated that. Richard Stanek–then a Minneapolis cop, later Hennepin County Sheriff–tried to get me on a terroristic charge! The cops would pepper spray me in front of the clubs, with hundreds of witnesses. Chief Axtell got to know me then. One night I bought roses for all the women at a club. When the police saw that, they wanted to embarrass me. They grabbed me, arrested me for a fake case.

A Muslim in Prison on 9/11

I was in Roseville, trying to get a night of sleep. The cops came into my hotel room. The whole thing wasn’t legit. Yeah I had drugs on me, but they had no legitimate reason to come to the room. They took me right to jail. I didn’t fight it. I was wrong. I had the drugs. They charged me with first degree possession of a controlled substance. I did my time as honorably as I could.

I went in at 21, finished that sentence at 24. In jail I was a practicing Muslim, going to temple each week. I carried the books. Autobiography of Malcom X, Elijah Muhammad’s Message to the Black Man in America, ready to have a conversation about the books. I was still a gang leader though, selling weed.

Guards didn’t like me. When I entered they had me on the STG list— security threat group — someone who had to be watched. I was trying to figure out how you get off that list, but anything I did or said, I was going to solitary. They wanted to stick it to me. I got in trouble for questioning. They just want you to be a good slave.

When the Twin Towers fell, I was put in the hole just for being Muslim. That was beyond my comprehension. Did they really think I was in jail masterminding mass crimes? I couldn’t understand that.

Prison Labor

At St. Cloud Penitentiary, they paid me 12 and 1/2 cents an hour to work in the kitchen. I said, “That doesn’t make sense. Whoever heard of a half cent? Why not just pay us 13 cents? They’d say, “You want to get less?” I’d say, “Y’all got less than 12 and 1/2 cents?” Those interactions got me in trouble.

Some people felt pride in their prison jobs. They’d say, “If we work hard we can get these dishes done early and then we can just sit back and rest” I didn’t feel that way. My mentality was, “I don’t like sitting around talking to y’all.” Half of them didn’t have a GED, never had a job, never played sports. I didn’t feel like I belonged there. Whenever we had time to talk, that’s when fights happened.

People carrying 99 years weren’t working for early release. They wanted to fight. I used my privilege, my height and strength. I saw people getting depressed in those cells. People taking penicillin and trazodone. I had never seen that before.

I didn’t want to beef with the Native Americans, with the Latinx folks. I always tell people, if I could deal with prison politics, I can deal with any of that shit out here. It’s heavier in prison. Winning an argument means more in prison.

Halfway Free

After prison I lived in a halfway house in St. Paul for six months. The blessing about being in that house, was that Hazelden was doing a documentary, Life on Life’s Terms, following people who got released from prison on drug charges. They filmed me for eight months. I’m in that documentary saying, “This is a set up. I’m here, ready to go, and you are imprisoning me again”

Being in that house did not feel like freedom. Jack Strawder, Black guy from Atlanta, worked there. He’s a friend now, and I love him. Not then. He told me I had to mop the floor his way. I wanted to get out and find a job. I was fuming. My first four days of “freedom” I was locked in a house.

The staff pegged me as trouble. I wanted to show them. My first day outside, I’d get a job.

Finding Work and Dodging Cops

The meat plant was hiring a lot of people. I couldn’t do that. I was playing cards with a guy, Shannon. He told me Holiday Inn was hiring. He had an interview on Tuesday. I went there on Monday, spoke with the manager. I told her I’d just got out of prison. But I had worked jobs. The most recent was the Family Dollar in St. Paul. She believed in me.

I came back to the halfway house and said, “I got a job! I gotta go get clothes.” That created a big hoopla in the house. They couldn’t believe it. They couldn’t fuck with me anymore.

Then I remembered Shannon, the guy who told me about Holiday Inn. I said to him, “I told them about you. You’ve got the job.” He did get it.

I became a supervisor after three months, helping with conventions, weddings. Still, everywhere I went, the St. Paul police were on my ass. I was trying to balance between St. Paul and Minneapolis, ducking and dodging to keep away from the police. Any police contact was a probation violation, no matter the reason. My parole officer’s advice was, “Stay inside.”

Looking for Housing with a Felony Conviction

I started looking for a place to live. No one wanted to rent to me. In the Hazelden documentary you can see me in tears saying, “I know if I sold drugs I could get myself a place to stay.” I was paying application fees, $25 here, $50 there, just to have them tell me they would not rent to a convicted felon. I thought when I finished my prison sentence I paid my dues.

A lady I worked for during a convention at the hotel was impressed with my stellar service. Hearing about my housing search, she told me she owned an apartment complex.

“Come to my office next week.”

The place had a pool. It was amazing. I started imagining myself there. We were filling out the application. It got to the question: Have you ever been convicted of a felon” She said, “Write No.” I said, “But I have been. She said, “Sorry, I can’t let you in.”

They filmed me at the Holiday Inn, telling that story. The head chef heard me. He was the manager of some properties. He said, “ I’m going to help you out. Get your first and last month’s rent together.”

I appreciated it, but his property was in the ‘hood; drug dealing, gang members, extreme poverty. While living there, I got into a relationship with the manager of the property, a beautiful woman, much older than me. She helped me get a caretaker position in another building. Free rent. She was from Texas, about to returning to her home state, and she wanted me to go with her. I had to tell her that wasn’t happening.

Metropolitan State University: Accidental Refuge

I was 25 when I started at Metro State, in 2004. My start was inauspicious and not planned. I had just gotten high and I was driving, vulnerable to a police stop. I parked at the University and went inside, just to get off the road. Advisor Bruce Holzschuh could smell the marijuana. He was like, “Are you sure you’re ready for this?”

Filling out the forms, I discovered I couldn’t get financial aid. I challenged the system. Challenged TRIO. It didn’t make sense to me that violent offenders could get Pell Grants, but not people caught with drugs. I knew that wasn’t right. I didn’t know yet how to fight it.

Excelling in College, Surrounding Myself with Revolutionary Black Leaders.

My first semester, I took Constitutional Law with Bob Fox, Abnormal Psychology, and African American History with Sam Grant. I walked into class everyday with Black leaders on my shirts: Assata Shakur, Nelson Mandela, Steve Biko, challenging my professors.

I got a four-year degree in three years, got scholarships, bought a car. The African American Student Association (AASA) elected me President. We fought for Ethnic Studies, challenged a racist writing teacher, raised funds for Hurricane Katrina victims, did voter registration drives, and built alliances with other student groups like Women in Power, and LGBTQ students.

My advisor for the AASA was Chuck McDew, an organizer with SNCC. I spent time with his whole crew. They told me about how they shut down Woolworth’s and how Chuck got his jaw and shoulder broken. I got a movement education, and I was in the center of important work. Keith Ellison, the NAACP, were all around me. I volunteered for Angela Davis, worked for Freedom School.

Confronting The Chief of Police in Class

I was working 32 hours at the halfway house, 20 hours as a student worker, taking five criminal justice classes. St Paul Chief of Police Harrington’s taught a “Gang” class. He knew me: Chief in the Streets. I was disgusted with him, a Black Republican engaging in racial coding. He didn’t know shit about gangs. One day I came to class with a Fred Hampton shirt on, with the quote: “You can jail the revolutionary but you can’t jail the revolution.” He kept looking at that shirt. He said, “I heard Fred Hampton preach once…I guess you could call that preaching.”

I said, “Don’t play about Fred Hampton. He knew way more than you, no matter what age you are. The shit you’re doing is really wack. You’re a cop with Black skin.” I drilled him for about 15 minutes. He kept on trying to interrupt to prove his point. To this day, he can’t debate with me. I’ve gone one-on-one with him in front of the Met Council. He can’t keep up with me as far as intellect. I recognized this when I was 26, and started building my skills.

Getting Set Up for Drugs

While I was in Harrington’s class I got set up for drugs. I can prove those drugs weren’t mine. We have the text messages. A close friend from prison was working for the police. He has since apologized. I was on a high speed chase with police that lasted 52 minutes. My appeal is online. I went to jail. My bail was set for 75,000. My friends at Metro State and people in that activist community like Mahmoud El Kati stood by me.Keith Ellison Wanted to be My

Keith Ellison and Julian Bond

Keith Ellison wanted to be my lawyer. He came to visit me at the jail. The first thing he said to me was, “I need $5000 to do anything for you.” Cold as hell, out of the gate. I said, “I’m going back to my cell, you can just leave.” He said, “Wait, tell me what happened.” I said, “You know I can’t talk on this phone. These calls are recorded. You’re a lawyer!” I hung up, went back to my pod and called my team to strategize.

Community raised the money for my bail. I went with Wolanda Shelton, an amazing Black woman. She was soft and tender, what I needed. She said, “Don’t talk on this phone. I’m gonna get us a place to meet.” She had strong roots. She needed $2500 more than Ellison, but it felt right. A lot of times it takes a woman to get it right…

I told her, “You know they set me up with that shit.” The police came to my house the week before and took pictures. I had no time to be dealing drugs. It was a conspiracy to cut me down because I was a high-profile activist. I had just spoken on a panel with Rose Brewer, Keith Mayes, Sam Grant and Hosie Thurman.

Next time I saw Ellison I was with Julian Bond. We brought him to campus. He said America scrambled spelled “I Am Race.” I have a picture with me and Bond. I walked him around campus. He seemed disappointed that I was taking him around. I held the mic when he talked. Ellison wanted to ask a question. I decided not to treat him like he treated me when I was in that cell. I gave him the mic.

The Trial

During the trial, over 300 people came to support me. I came with 40 Black folks. Sam Grant spoke on my behalf. I understood this was important for the community. I was the face of Chosen to Achieve, a Black-led mentoring agency in St. Paul. They took me off the list. Freedom School came with a busload of kids, protesting outside the courthouse chanting, “Free Jason!” My lawyer said, “Get that school bus out of here. They are going to make you an example.”

The best I could get was a year in jail and a twenty years of probation. The prosecution brought in a young attorney who talked about being an example for kids. There were a whole row of racist cops in the jury pool seats.

College Student, Doing Time

After that I got more serious about my restorative justice work. I faced a year in jail. I got work release so I could leave my cell to go to class, and work at Amicus. That was the deal. I had to take a psychological evaluation and I had to pay a 2,500 fine. They tacked that on.

Every time I came back into the jail, I was wearing the face of a Black Revolutionary on my shirt. One day I had on Mumia Abu Jamal. The guy checking me in looked at my shirt and went to his computer. He came back out with gloves on. “You really coming in here with the face of a convicted cop-killer on your chest?” I said, “Convicted by a bogus -ass system.” Later, another cop—a white guy with a mohawk—came to my cell while I was sitting at my desk doing my homework. I could have been killed that night. They took away my weekend privileges. I had an important event at Metro State that I missed. I had to stay in my cell for the next three days.

Thinking About Harriet Tubman

My wife and I got together that year. She was a student at Metro. She got pregnant. I had to sneak around my restrictions to be a responsible partner and daddy-to-be. When I was sneaking into doctor visits and hospital tours, I thought about Harriet Tubman. That is why she is my hero. I always said she was way more important than Dr. King. She was an abolitionist.

I asked the judge to allow me to see my baby being born and to go to my graduation. President Wilson Bradshaw and Mahmoud El Kati wrote me letters. I got to be at my graduation. When they said my name the place erupted. That diploma was bigger than me. It was for the movement. I did a backflip. Two hours later I was back in my cell.

Out of Jail in time for Fatherhood

My daughter was born April 29 and I got out of jail May 7. When I made it home, to 29th and Penn in North Minneapolis, I was holding that baby, smiling so hard. But I didn’t want to raise my baby on that block. We made a rash decision to just go to the suburbs. We didn’t know anybody in Apple Valley. My wife grew up in East St. Paul. Her whole family lived in North Minneapolis, but I couldn’t afford to get hounded by the police, especially with now that I was a father. That was one of the best decisions. I’m not advocating for moving to the suburbs, but going to a place where people didn’t know me, gave me a lot of breathing room. We lived in a condo.

Working with Families of the Incarcerated

Right away I began working on a Masters, online. Judge Pam Alexander, (she always had a level of respect for me), allowed me to do my 450 hours of community service, working with parents of incarcerated people. Afterward I got full time work at Amicus, helping people coming out of prison. I published an article for the Justice Where Art Thou Conference. Malcolm Gladwell was keynote, and Judge Alexander was a speaker.

In 2007 I became a restorative justice trainer. I started helping sex offenders, which was hard for me. That was one of my strongest biases. In three years we reduced the sexual victimization rate in Minnesota by 76%. That is documented.

Back at Metropolitan State as a Professor

In 2009 I decided to leave Amicus on the highest of standards. I was starting my consultancy service when Metro State called, asking me to come teach diversity issues and criminal justice.

At first I co-taught with Police Officer Paul Schnell. We challenged each other in class. I’d say, it’s how you view me that is the problem. He acknowledged that he’d been the cop who put a gun to the head of a Black man and said, “Don’t you fucking move.” I talked about what it was like to be a recipient of treatment like that. Our classes were always the best.

We took it to Chicago, attending a criminal justice conference together. He met my mom. She got to see me presenting on a big panel in front of 400 people, with giants in the criminal justice field. They gave her a huge standing ovation.

She is the true MVP. I’m doing what my mom should be doing.

Teaching Prisoners and Cops

My life kept getting better. As a teacher I made it my job to lift up the culture and contribute to Black excellence. I almost left after one year because of the racism, but there were those who loved me who pulled me through. Others who loved me when I was climbing, couldn’t handle me as a professor alongside them; they with their Ivy League degrees, me formerly incarcerated and still on parole. They were threatened.

In 2013, I became an Assistant Professor. That year I also became a Bush Fellow. I was carrying a 4/3 load, going to trainings. I even taught a course inside the prison, taking Metro students to learn alongside people serving time. In 2014 I published a memoir.

At the same time that I was publicly analyzing the Jamar Clark case, and protesting in the streets yelling “prosecute the police,” I had six Minneapolis officers in my class. They still say I’m the best professor they had, even though they don’t agree with my philosophy or the fact that I lift up Angela Davis, (Prisons Are Obsolete) and Michelle Alexander, (The New Jim Crow.)

The duality was difficult. Metro was triggering, working with students who were cops, and studying to be cops. Students would be in the hallways, working with dummies, wrestling them to the ground. Mad triggering.

Becoming President of Minneapolis NAACP when Jamar Clark was murdered

In 2014-2015, I got heavy into the movement. I went to Ferguson, came back to join the NAACP board, becoming the criminal justice chair for an all Black, women-led, Minneapolis chapter. In 2016, I became President. .

When the police murdered Jamar Clark, I had already spent the time in Ferguson, so, unfortunately, I was prepared for a police killing in Minneapolis. It was emotional for me. I was at the scene at 8AM, tea in hand, analyzing the blood, talking to people. I was there when Jamar’s dad came up to me and said, “What happened to my son?”

At the occupation of the 4th precinct I had to be professor, healer, and organizer. I held restorative justice circles. People were coming down who were transphobic, homophobic, Islamophobic, atheists. Some people wanted to burn it up. A mix. We had 200 people in one circle. Angela Conley emerged in those circles. I put my beef with Ellison to the side to build community, though I wasn’t sure he was there for the right cause.

Confronting Mike Freeman

I analyzed Mike Freeman’s press conference in an article co-written by Rachel Wannarka, published in the Star Tribune. He lied seven times. I pointed out five times that I had strong evidence he was lying. After it was published Freeman called, pleading for a meeting. I took two months before I met with him. I wanted him to sweat, to stop playing. He shouldn’t have lied.

When we finally met, he had his criminal justice person at his side. I had my squad from the NAACP. He started playing, talking about his Dad, into his personal story. I tapped him and said, “Why did you lie and say Jamar Clark said he wanted to die?

He replied, “I shouldn’t have said that.”

I asked him, “Do you have a conscience? We can work together on stuff; get some people home on bail, but if you lie again I’m calling you out.”

That work was risky for me. If I had gotten arrested during those protests I would have gone to jail for 110 months, due to the 2005 set up.

We Learned how Minneapolis Works after the Murder of Jamar Clark.

Systems were exposed. The activist world was exposed. What do we know now?

- This precinct used to be a community center. The Way was a positive place for Black people. Now it’s a police station.

- White supremacists can shoot activists in Minneapolis and not really be punished. Allen Scarsella shot five people. We had to keep the pressure on just to get a conviction. There are questions about where he is imprisoned–that he is being held in a non-DOC (Department of Corrections) facility.

- How the County Attorney worked.

- How much homophobia we have in the movement.

- The level of addiction and poverty present in the area.

- The skills we have.

It started with Travon. Ferguson enflamed the movement. The Minneapolis’ occupation of the police station for 18 days, helped to build it.

Voting with a Felony Record

I couldn’t vote for most of my life, so I’ve always looked at politics differently, knowing I had to impact the system from outside of electoral system.

I did ten years of probation. The judge agreed on February 2016 to commute my probation. Now I am free. I can vote. Now I have experience working for politicians, and again I find myself charting a political course outside of the electoral system, building movements.

Hamline University

In 2017, I told Metro State, you gotta get someone else for next semester. I’m not staying here. I left not knowing what I would do next, but Hamline called right away. I don’t think I even filled out an application. The Criminal Justice and Forensic Science Department said, “Roll like you roll. We won’t censor you.”

I started as a visiting professor at Hamline, when Mayor Carter called. I didn’t know him, but he had the energy. Carter said he wanted me to run all his criminal justice stuff. He said I just need you to be you. You don’t have to change the way you dress or what you are doing. Nothing. I am going to pay you $103,000 and all the benefits.

I didn’t want to leave Hamline: I was going to get tenure there; but it was an opportunity I couldn’t turn down. As President of the NAACP I was working on Valerie Castile’s art exhibition for Philando, surrounded by the leadership of young Black women. Our Criminal Justice Reform Committee, led by Dr Raaj, was kicking ass. We pushed for Warrant Forgiveness Day, using that restorative approach. I had two months to get my NAACP team together before I left to join the St. Paul Mayor’s leadership team.

Mayor Carter’s Advisor on Criminal Justice

I sat down with Carter’s whole team. They didn’t have an analysis of criminal justice. I told them we had to have a goal of abolishing the police.

Without support, I did a hell of a job. The Mayor never gave me a budget, or backed my ideas, or come to anything I did. I worked with the police, the sheriff’s office, with activists, with the formerly incarcerated, with gang leaders. Like a big homie from the gang world, I had rapport with them all, and the power to get them to stand down, because I was credible. I was the perfect person to train the police on truth and reconciliation, but the ego of the Mayor was too much. He was fighting against my work, using my name, playing a different game. He brought in the feds!

Money for Re-entry, Not Police

The straw broke when Carter undermined my authority in a meeting with Chief Axtell, and Lindsey Olsen the Chief attorney and other municipal leaders. Carter had announced we were getting Bloomberg money for public safety. He put forward a proposal for how to use it. This was the first time I heard his idea, though I was his criminal justice point person. He wanted to use the $ for police training, saving a little for, “place making”— fixing up neighborhoods and helping a few people.

When the floor was mine I said, “Don’t give any money to the police. Don’t work on place-making. Spend it on the people. There are 385 people in the workhouse about to get released. Spend it on getting them driver’s licenses and places to stay. Then, give services to addresses that call the police five times a month, so they don’t have to call the police.”

Chief Axtell said, “Jason is right. Don’t give us anymore money.”

Lindsey Olsen said, “Jason is always right.”

The Mayor said, “Nah.”

Resigning From Mayor Carter’s Staff

That was it. I was out.

I resigned on MLK day, 2019. This has been the deadliest year. Now he is doing these community conversations. I have to block a lot of that out so I can stay focused. It is uncomfortable to be going against a Black mayor. His dad knew me when he was a cop and I was on the streets. He knew my tenacity and energy. His dad cannot look me in the face and say I did anything wrong. No one will tell me I did anything wrong, but a lot of them will still support the politicians.

I had to leave in a bold way. I’ve learned that people with power—Carter, Ellison —don’t always live up to their words. I am wary of the electoral process. Sanders, Warren… I’ll be involved, but in a different way.

Humanize My Hoodie

The idea began with the senseless killing of Trayvon Martin. I started to wear a hoodie even in professional spaces.

Fall semester 2017, I was going to do some research with my students at Hamline. I wore a hoodie for every class session. I wanted to see if a semester of exposure to their professor standing in front of them in a hoodie, would decrease their threat perception of a Black man, their fear of me, their tendency to dehumanize me.

On August 14, 2017, I got my family together just as they were getting ready to go out the door. I put on my Black Lives Matter hoodie, and a stack of books and gathered my family around me for a photograph. The picture showed I was a husband, a father, a professor. In a hoodie. I said, “Humanize My Hoodie.”

Throughout the semester, students had to wrestle with how they perceived me. One of them said they thought I was lazy, not a real professor. That is what I wanted to fully understand.

Healthy Masculinity

That’s the academic side. On the movement side, Humanize My Hoodie began resonating with people all over the world. Andre, my friend from Waterloo Iowa, had become a fashion designer. We had already been working together on different things. He had organized a book-reading for me in Waterloo. I asked him to design the Humanize My Hoodie message. We had to sign the papers, do the business side of it. In three weeks we had it on our bodies.

Doing this with someone has strengthened our friendship. I tell him I love him in public. People need to see healthy masculinity. We know the ancestors are guiding us, lifting us up.

Humanize My Hoodie Gaining Fame

Someone nominated me for a John Legend award. When Legend tweeted, Meet Jason Sole and his Humanize My Hoodie movement that opened us up to his base of 20 million people to us. We have a movie, a book. All of that attention is a blessing and a curse. I had to decide to keep my support circle tight. We face questions like, should we sell at Target? Would the meaning get lost?

The conversations are what is important. They are happening in the streets and classrooms, and in intentional circles. When people have these sweatshirts on their bodies the conversations are on the spot and more than we could imagine. This garment is empowering.

Empowering Youth Voices

We gave out 250 hoodies for Freedom School at Alex Haley farm in Tennessee. The things that kids said were jaw-dropping. One girl, seven years old said, “I feel like people will see me as a human now.” Another kid said, “Maybe you will see me now.” After that I needed someone else to moderate. Too much emotion.

One 18 year old sent us a picture of him, sitting on the college steps, heading into class his first day of college, with the hoodie on. That’s beautiful.

Some white allies wore it to Thanksgiving dinner, knowing it would start a conversation. They were armed to say, “I’m wearing it in solidarity with my Black friends who are dehumanized, criminalized, and find their lives in danger for wearing a hoodie.”

Kids at Lucy Laney are wearing them. At Soul Bowl restaurant in Minneapolis the staff wore a special version created just for them.

In September we participated in a New York fashion show.

Returning to Waterloo to Confront the Racist Coach

In December, Andre and I went back to Waterloo to confront our racist coach and another racist white guy who came to the Waterloo City Council meeting and railed about kids in hoodies ‘dressed to commit crimes.’ We connected with the Black radio station, did an interview with them. They did the work to bring a group together. The people who came out were young and old. We did a circle, gave out 275 hoodies. It was beautiful.

Next stop, Chicago.

Now we are confronting hoodie bans in malls and schools. People are saying, can we humanize the hijab? Can we humanize the skirt? I say let’s keep talking about it! We are trying to create more leaders with this movement. And we are.

Hopefully we won’t have to wear these hoodies in two years. We will have humanized the hoodie.

Defund the Police

Minneapolis activists with Reclaim the Block are asking, why do we need cops? I say, More Cops equals Less Black People. Mayor Carter gave the city of St. Paul nine more police officers at a cost of $900,000. Look at what happened! More killings in 2019 than any other year!

Do cops keep us safe? If you’re white or wealthy, for sure. Not if you’re poor. Not if you’re Black, Latinx or Indigenous. It’s disrespectful that we have to have this conversation over and over.

Thaiphymedia

Perspective

I come from prison, from getting shot, from the flames, still I’m sane and healthy, and I’m lifting up others. My wife and children are doing well, so I am blessed. I’ve lived in environments designed to break you within a small window of time. I am grateful to have made it out with my whole sanity. It could have done something really damaging to me, like it did to so many of my friends. As a professor, a professional, I can limit the amount of contact I have with people who don’t like my brown skin. I am trying to feel that out. I can step out when I feel like it, write a book, a movie, but I am always cognizant of what it is like to be that tall, Black, twelve-year-old boy.

After the Murder of George Floyd and the Minneapolis Uprising: Defund Police!

Abolishing the police does not mean there won’t be accountability for people who harm others. Divesting from police means that money can be used to house the unhoused. Divesting from police means that we can provide culturally specific drug treatment for those struggling with addiction. Divesting from police means that we can provide more jobs and business ownership to youth. These three things make us safer. We can hold people accountable without putting them in cages. If necessary, we can discuss what a community holding space looks like.

Six of my friends and I reduced crime for years in Saint Paul. We did so well it was co-opted by the government. Think about how I helped create a model that reduced sexual offending back in 2007.

We watched the police lynch George Floyd. If you don’t believe in abolition, it makes me feel like you’re okay with a cop possibly strangling me to death. Their training doesn’t work. Our data tells us that we are being hunted by police overseers.

A world without police officers is possible. We know amazing therapists who are also licensed to carry. They would only possess a firearm if the situation required one (e.g., defense against White supremacists). We know many aunties who can deescalate in dangerous situations. We already have the solutions; we just need the oppressor to stop oppressing us.

#AbolishThePolice