An article in the Minneapolis Star Tribune reported that all Jews supported Israel. I called up and said, “That’s not right.” The next day the reporter was in my office with a photographer. When her article came out, on the front page was a bleeding Israeli woman, crying out. On page three was a big picture of me.

—Lisa Albrecht

Photo: Eric Mueller

People think of New York City as highly integrated. In 1951, when I was born, the Forest Hills neighborhood of Queens was a segregated White Jewish neighborhood. The only person of color I knew was the maintenance man, who was Puerto Rican.

Neither of my parents went to college. My mother had polio when she was a little girl. She had several miscarriages before she had me. I am an only child. My father was a textile salesman. He worked for a non-union mill in North Carolina. He and my Mom would vacation, by driving south, stopping to visit my father’s customers on the way. I recently found a photo of my Dad during one of those trips, standing in front of a Confederate flag.

My parents were conservative, but they were also class conscious. We lived in a rent-controlled building. As renters, we were organized. If there were problems with the building, Dad would hold meetings with the other tenants in the lobby. We would put up signs in the elevators and stairwells. We would withhold rent and put it into escrow until the landlords did what they were supposed to do. We need this kind of renter organizing today.

I was a tomboy. There weren’t a lot of choices for girls then. I played softball on the Lassie League. We played on the crappiest fields, compared to the boys in Little League. I loved it. I could really slam a softball. I had short hair. I didn’t come out until my mid 30s, didn’t know the word lesbian until I went to college.

Encountering Radical Feminism in Buffalo, New York

I went to the University of Buffalo in 1970, and majored in English. This was the beginning of second wave feminism, when women were demanding changes in the curriculum. I took my first Women’s Studies class my senior year. It was taught by a collective—a professor, graduate students, undergrads and community members without college degrees. We sat in a circle and rotated speakers. Students called on other students. I thought it was bullshit and gave them a really hard time. It wasn’t my thing. Years later when I taught Women’s Studies courses using similar teaching strategies, I would tell my students about my initial attitude when first exposed to these teaching methods.

I graduated in 1972, moved back home and worked in a collection department as a secretary, typing up overdue notices for credit cards. I was in a secretarial pool. This was before computers—you had to type out every little thing. Living at home was a challenge. My mother wasn’t healthy and my father would use that to rein me in. My outlet was photography. I had taken a class in college. I would escape to take photos.

My parents were very proud of me for graduating from college, but we didn’t see eye to eye. When I went to my first anti-war march on 5th Ave in 1972, my father yelled at me. He participated in the hard hat, pro-war march a week later. He was a conservative Democrat who served as an election judge every year. The last year he did it they needed someone on the Republican side because they need to have balanced judges. He registered as a Republican so he could serve.

I decided to return to Buffalo and get a teaching license, because that is what a woman did, who did not want to be a secretary. At that time, all you needed for a teacher’s license was four courses and six weeks of student teaching. I got a position in rural upstate New York near Plattsburgh. Though I was in a very heterosexual place, that was when I started thinking romantically about women. On the weekends I would drive to Manhattan and head to a smoky lesbian pick-up bar in the Village, called the Duchess. I had my first relationships with women. Tried it out.

I taught high school English for 2 and a half years before I was laid off during retrenchment— last hired, first fired. I loved the teaching but the social scene was difficult. I wasn’t in to polyester. I decided to go back to Buffalo to get my PhD in Curriculum and Instruction. I learned how to teach writing.

Back in Buffalo, I found a lesbian community around the women’s book store EMMA, named after Emmas: Madam Emma Bovary, and Emma Goldman. I volunteered there. I was out, and had a lot of girlfriends. And I become involved in the book world. I am still sorting out and giving away books from those days.

When I graduated and was looking for jobs, my mentor, Elizabeth Kennedy thought the University of Minnesota would be a good fit. She said they had an established Women’s Studies department. I was lucky. There were lots of jobs in those days. By the time my own students got Ph.Ds, jobs had become scarce. Some have become administrators. Others are adjuncts, wandering from place to place, saddled with debt.

General College, University of Minnesota

I was hired by General College at the University of Minnesota to teach basic writing. I moved here in 1985, with my partner at that time, Bev. I didn’t come out immediately. I was testing the waters. I did after about three months.

My first summer here, was so hot! My partner and I would unpack, and look for a lake close by. That’s how we learned our way around town. I loved the lakes. Water is so important to me. I have one tattoo: a wave. It sits over my heart.

I loved teaching at General College. I taught writing as social justice. I did not teach grammar. I miss those students. They are not at the University anymore. They were students of color, single moms. They had diverse experiences to bring to the classroom.

Every five years or so they tried to close us. It was ugly. Each new University President tried his hand at it. Among the Regents, Josie Johnson consistently fought for General College. Most Regents, however were just waiting for the right time to get rid of us. We would protest, stand in front of Morrill Hall picketing. They would misuse data to argue that we didn’t graduate students in a timely manner. In fact, we didn’t graduate students at all. Students would transfer to the college of their choice. Our data showed, if you started in the College of Liberal Arts of General College, graduation rates were comparable.

Social Justice at the School of Social Work

As that last battle over General College was playing out, I realized I had to figure out where I was going to go. I had heard the School of Social Work wanted to start a social justice program. The Director of Social Work was Jean Quam, who later became the Dean of Education.

Ironically, it was the same Regents meeting where they officially closed General College, that they approved the Social Justice Minor in Social Work. At my job talk for the position, I discussed the importance of working with White people for racial justice. I was in Social Work my last twelve years at the University.

Minneapolis Civil Rights Commission

When I first moved here, I went to a presentation at the Public Library about Civil Rights and decided I wanted to get on the Minneapolis Civil Rights Commission. The Commission– judicial arm of the Civil Rights Department–is a resource for anyone in a protected class, who thinks they may have been discriminated against. If investigators in the Civil Rights Department find probable cause, your case goes before three Commissioners, who have the power to award damages.

The Commission is made up of lay people and lawyers, appointed by the City Council. Sharon Sayles Belton, who was my Councilperson, and Councilperson Brian Coyle, who died of AIDS a year later, supported my appointment. It’s a volunteer position with a stipend to cover expenses.

I began in 1990, served twelve years, and was then Commission Chair for two years. Though we didn’t always agree, everyone I worked with was committed to civil rights. In 1993, sexual orientation was added as a protected status. We saw the first case of discrimination brought by a lesbian couple and other first LGBTQ cases.

As chair, I planned the meetings, tried to get the word out. (Too few people know this Commission exists!) It was a great learning experience. I learned about the law. I learned how City Hall works. I learned I didn’t want to run for office. ( I watch Andrea Jenkins and Alondra Cano, and think about how difficult their lives are.) Most important: I learned how to speak up in the face of injustice.

Chronicling LGBT Culture

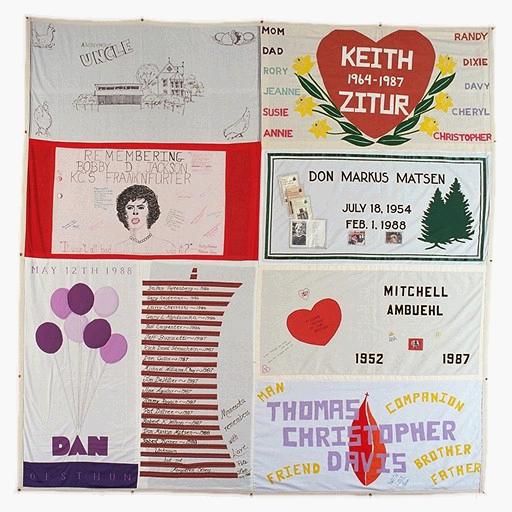

Don Markus Matsen, a Twin City flight attendant who was HIV positive, wanted to give back to the community before he died. He founded the Evergreen Chronicles a journal of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Cultures. It had a four-person editorial board: two lesbians and two gay men.

I was one of the four editors. We would get a stack of manuscripts, have a meal together, go through the pile, decide what to publish. We accepted poetry, prose, and photography. It was a day-long process—a labor of love. The publication lasted from 1985-2000. We distributed it at gay bars, at the Gay male bookstore A Brother’s Touch, the feminist bookstore, Amazon Books, and at GLBTQ parties. We did readings to raise the funds to get it out. One of the early editors, Doug Federhart, went on to be a leader at OutFront Minnesota

Keith Gann, who also was an editor, was the first HIV positive person to speak at the Democratic National Convention in 1988. I was part of his care circle when he passed away in 1990 and wrote a piece in his honor.

I didn’t hide these activities while I was teaching basic writing at General College. In my tenure case it was a slight battle. Adrienne Rich wrote a letter for me and talked about the importance of the Evergreen Chronicles. They didn’t like that stuff, but I think being on the Civil Rights Commission gave me clout. They didn’t mess with me.

Project South

I was on the board of Project South: Institute for the Elimination of Poverty and Genocide, because of my work with Rose Brewer. We did movement-building. Their board included people who were on welfare, people who were in high school. We would meet in Atlanta four times a year. I still use their model of organizing. They focused on three pieces: Consciousness, Vision and Strategy. You have to get people on the same page, to do work together. You have to decide together how you want the world to look, and then you are ready to develop strategies. It is a great model for organizing. I use it in my own life, as I move through my own transitions and transformations.

Tikkun Olam and the First Intifada

The principle of Judaism that I live by is Tikkun Olam—being there for justice.

My parents didn’t belong to a synagogue because they didn’t have money. I don’t belong to a synagogue because of Middle East politics. I belong to Jewish Voice For Peace — a national organization with local chapters. We support the Boycott, Divest, and Sanction movement.

The first Intifada was in November 1987. I felt like, how can I speak up if I don’t go there? I found the Middle East Children’s Alliance (MECA) in the Bay area. They were taking a Women’s Peace Brigade to Israel and Palestine. You had to apply. The woman who founded the organization, Barbara Lubin, had been a Zionist Jew.

I went off to Palestine right before George Bush Sr. invaded Kuwait, December 1990. We stood out with the Women in Black on protest lines. We stayed in East Jerusalem, which was all Palestinian then. We stayed in Gaza, which was open then.

That trip broke my heart. I got sick. They took me to a clinic in Gaza. A Palestinian doctor was going to see me. I freaked out because I had my Jewish star on. He knew MECA was there to work in solidarity. He put the stethoscope on my chest, next to my Jewish star. He insisted on giving me a bottle of medicine, even though there were only three bottles there. I didn’t want to take it.

When I came back, there was an article in the Strib by the religious writer, Martha Sawyer Allen, about how all Jews supported Israel. I called her up and said “That’s not right.” The next day she was in my office with a photographer, interviewing me. The morning the article came out I got up at 5AM to get the paper. On the front page there was an Israeli woman crying out, bleeding. On page three there was a big picture of me.

My first reaction was fear. What happened, was not what I feared. I did get the silent treatment from the mainstream Jewish community and when I spoke on Israel/ Palestine, people came out and heckled me, but I also got some lovely emails from people around the state.

It felt really important to me to speak out. There used to be a place on Hennepin Avenue—Gelpes Bakery. We would picket on Friday afternoons when people came to pick up their Challah. There were men there who looked like my father, who spit on me.

It is a constant dance to celebrate my Jewish roots without compromising my position on Israel/ Palestine. For a while I was in a klezmer band, Tsatkeles, playing yiddish music. I played percussion. Judith Eisner led the group. I loved playing the music. We stayed away from Middle East politics.

This year for the High Holidays, I live-streamed services, through Jewish Voice for Peace, so I could still celebrate the New Year.

Most mainstream Jewish organizations and synagogues still support Israel. The propaganda starts young. If you have a bat mitzvah or bar mitzvah you get to go on a free “birthright trip” to Israel. You see only what is beautiful. You don’t go to the West Bank.

Even so, today there are more young people speaking out. There are alternatives for them. In part that is because the killings of Palestinians are off the scale. It cannot be ignored. It feels as if more and more people are seeing the horrors of what is happening. Still, people like Ihan Omar take all this heat they don’t deserve, for speaking out.

Eldering

I retired recently. It’s a young person’s world. Events often start too late at night for elders. Access is an issue.

My partner Pat was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s fifteen years ago. She has lived in a residence in Richfield for the past three years, founded by Sally Kundert, and now run by Susan Eckstrom. Cecilia’s Place is not a nursing home. Five women live there, each with their own bedroom. There is a small loving staff and little turn over.

I see Pat every weekend. People ask, “Does she know you?” I don’t know. I have faith that she knows she is safe and loved, even though she can’t say that.

When she first got the diagnosis, I went to the Alzheimer’s Association. They meet with you once and send you home with a huge stack of literature. Being an organizer, I sorted out everything and farmed out each piece to a friend. I said, “Give me a one-page summary.”

I worked with a group to start an LGBT senior caregiver’s network. We wanted it to look like the diversity of the LGBTQ community–multi-racial and cross class. The Wilder Foundation funded us for a year. We were all still working full time and we couldn’t get it going. Now Wilder has created a caregiver group for LGBT people. I volunteer once a month and co-lead a support group with a social worker through the Center for Aging. It has been really wonderful. I did a workshop on the North Shore on caregiving for LGBT elders. There were 50 people there–only a few who were LGBT–and they all wanted to know how to serve the LGBT community!

Now I am going to serve on the Diversity and Inclusion Committee of the Alzheimer’s Association. I worked with the state on a 2019 legislative report on Alzheimer’s. The Committee were mostly health care administrators who never had to wipe anybody’s ass. I was on the culturally responsive subcommittee. We went to the larger committee and we weren’t allowed to speak until they were all finished speaking. They looked at me like I was talking in a foreign language when I asked them what publicity they were going to do, concerning the report. I don’t think it has had much of an impact.

Mentoring

I think mentoring is a two way street. I get great pleasure from my contact with former students. They created my facebook page. I have a former student, Ilana Lerman, who works for Jewish Voice for Peace.

Another student, Sarah Kettering, went back to school to get her Masters’ in Public health after her father was diagnosed with Alzheimers. I went to her father’s funeral. She plans to focus on geriatrics. I learn from her. She learns from me.

Another former student, Alissa Paris, was in my class when Obama was President. When people would say, isn’t that great, we finally have a Black President, she would yell out, “No, he’s mixed race.” She founded the Mixed Race Conference in Minnesota. She contacted me to talk to White people who did transracial adoptions and had kids of color. She asked me to be there to support them. I had never been in a place with so many mixed race people. They talked about living in-between. I learned a ton.

I don’t have my own kids. These students are my children. It is wonderful seeing who they become, five and ten years down the road. These relationships keep me young. I write recommendations for them. A lot of them graduate with huge debt, majoring in things like political science and social justice.

I thought about teaching again, but I can’t stand these institutions, driven by money and class size, viewing students as consumers.

I had one class right before I retired that fought me. A couple students filed a discrimination suit against me, claiming I was transphobic, racist, and anti-disability. I was interviewed by the EEOC at the University for hours. They found me not guilty. My boss saw how hard I was taking it and offered me a paid semester off. I took it. The students got word of it and posted a message saying, “We won!”

Former students, when they heard about the suit, said “What?!” That support was wonderful.

The next semester, when I wasn’t teaching, I got invited by the Students for Justice in Palestine, to speak. I was one of three Jews there to discuss Anti-Zionism from our perspectives. It was my first time speaking, since the discrimination suit. I was nervous. Right in front, there were some pro-Israel Jews. We talked personally about our experiences. It went really well. I felt like I got my Mojo back. I came back to Tikkun Olam– never silent in the face of injustice.

Warrior for the Human Spirit

Meg Wheatley, author of Who Do We Choose to Be , has started Warriors for the Human Spirit. The organization is based on this principle: I can not change the way the world is. But by opening to the way the world is, I may discover that gentleness, decency and bravery are available, not only to myself but to all human beings.

I am learning how to be a human being again. I don’t walk around with my cell phone attached to my ear. We had two retreats a little more than a year ago. We met with Meg. It was initially challenging. Meg is a Buddhist. Her way of teaching which is not my way of teaching. You sit at the master’s feet to learn. I came to appreciate it.

She is now starting a teacher-training program and I got accepted. There will be a cohort of 15 people. We meet in March in Zion National Park in Utah. After the retreat we will have regular calls to train others.

We talk about how to not react angrily to what is happening in the world, how to be present for people and really listen. Soon after I started Warrior training, I went to a City Hall Planning Commission meeting regarding the overdevelopment of West Calhoun. I yelled out during the meeting because it was so clear they weren’t listening to neighborhood residents. That was the last time I yelled. It was not constructive. I had a statement to read. When I read the statement I did so angrily and it did no good.

We are on the brink of collapse as a society. I don’t say that too often — because if you are a parent of a small child, it is not something you can hear. But I cannot change the way the world is. Meg has studied 5000 years of civilizations rising and collapsing. Every civilization has collapsed.

Experience, Learn, Act

When I wanted to speak about Palestine, I felt I needed to go there so I could speak from experience. Now that I am an elder, I can take on elder issues.

I can stand up for racial justice, drawing on my experience as a White person. I certainly can’t speak for people of color. I can speak for White people. But I couldn’t do that without people of color in my life. I’m a lucky person in that way. There is plenty to do in Minneapolis on this front. We are not doing well, in terms of equitable development, criminal justice, or educational disparities. These are huge markers of racism in our city.

That is the challenge I give myself: to have the experiences I need to speak up for social justice from a position of personal knowledge. I’ll keep doing that until I kick the bucket.

(soundcloud of Lisa. October 2019. Everyday People Speak Truth to Power)

Minneapolis Interview Project Explained.

#megwheatley #evergreenchronicles #lgbthistory #lgbtq #minneapolisinterviewproject #lisaabrecht #Minneapolis