I met my friend Layla’s uncle in Iraq. He was a recently-released prisoner of war in Iran — thin and quiet, still unhealthy and traumatized. This loving family made a meal for us in their home. Their son loved Micheal Jackson. He asked me to moonwalk for him. I did. Most people would say I didn’t, but….I tried. All the people we met would say: “We hate your government, not your people.” That is hard for Americans to do. Instilling that outlook in people here is something I’ve been working on ever since.

—Jess Sundin

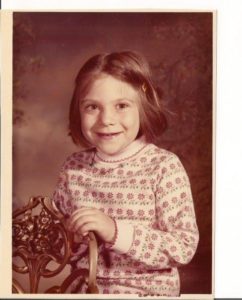

Working-Class Northwest Childhood

I grew up in a working-class neighborhood a couple blocks from my elementary school in a house that we heated with a wood stove. Cutting wood and going huckleberry picking were big parts of my childhood. My Mom was a nurse. My Dad was a factory worker. Most of my childhood he worked in boat manufacturing, though he was also a trucker. He is my adopted dad. His son from a previous marriage, my older brother, usually lived with his mom. I also have two little brothers, seven and nine years younger than me.

Spokane, Washington is at the foothills of the Rockies. It is the one city between here and Seattle — which is not saying much. With hospitals, it’s a hub for Eastern Washington and Northern Idaho. Growing up it was politically conservative, but the City Council is now Democratic. It is predominately white — about 85%. The Spokane Indian tribe is not far so there were some Native folks in the city and there were Laotian and Ethiopian immigrants in town. Latino farmworkers work nearby, but not many ended up living in Spokane.

I had major heath problems as a child, including many orthopedic surgeries. By the time I graduated from high school I had spent nearly seven years in hospitals. Much of that was at Shriner’s, which had its own school for kids. Tutors helped us with assignments from our regular schools. In Elementary school I started going to the National Institutes of Health, in Maryland, where doctors study my immune deficiency, Job’s Syndrome. I still check in with them. There are something like 100 people in the US with this genetic disease, which makes me something of a unicorn.

High School Environmental Activism

I was interested in environmental issues in high school because of my family’s lifestyle. We were always angry at the clear-cutters destroying our pristine woods. I founded an Earth Club and set up recycling in our school, which was novel at the time.

When I didn’t make the cut for orchestra in high school, I took up debate. There is a radical aspect to debate philosophy. I was attracted to that aspect of it. I learned about the US covert wars in Central America in the 1980s, through one of our debates.

My senior year —1990-91—was a big year in politics: the First Persian Gulf War, and the beating of Rodney King recorded on video, were formative experiences in my life.

Spokane is near an Air Force base. Many of those stationed there lived in town and their kids went to school with me. The town was polarized about the war. Kids of our generation hadn’t seen anything like it. (In comparison, for my daughter’s whole life there has been ongoing war.)

A student from Gonzaga University who coached our debate tournaments told me Macalester had an active debate team and a liberal reputation. Eager to leave Spokane, I wanted a bigger city—but not too big. The Twin Cities seemed just right.

Getting to the Twin Cities: Macalester College

I was disoriented when I first got to the Twin Cities. There were no mountains! I couldn’t figure out where I was. Through Macalester’s debate team I got to travel around the Midwest. I discovered that most people in this region don’t have a good sense of direction. I think it’s the lack of landmarks — no oceans, no mountains.

I suspected I got into Macalester because I wrote about my disabilities in my application essays. They wanted to tick off their “diversity” boxes, yet they housed me on the third floor of a dorm with no elevator. That gave me a negative first impression. Macalester was not a place that was true to its word.

The ADA was new then, but it was the law. Many public institutions had already made changes but the private institutions were behind. Connecting with other students who had disabilities — a friend who had lupus, another with learning disabilities, we were all having the experience of being embraced for our disability, while receiving no material support for our needs. That didn’t help our retention rates, which were nearly as low as for students of color on campus, for similar reasons.

I almost died freshman year from pneumonia and a collapsed lung. I was on my mom’s health insurance, but it was difficult to access so I avoided getting the health care I needed. I ended up spending a couple of months at NIH, where I, for the first time, met a friend who had Job’s. Within two years, she passed away at 30 years old.

Her death was traumatic for me, not just because I lost a friend. At 20, I was feeling my mortality.

In addition to disability rights activism, I was heavily involved in the Mac Peace and Justice Committee. I didn’t have enough energy to keep up with school and activism. After two and a half years at Macalester, I dropped out. My last semester, I failed every class except guitar, and called it quits.

Becoming a Full-time Activist and Socialist

I had learned about the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador from an older student at Mac who had been a regional director for the organization. After I dropped out I got more involved. I went on a delegation to El Salvador to monitor the first post Civil War elections in 1995. It was shortly after NAFTA and the Zapatista Uprising. CISPES seemed like a good political home for me to be involved in solidarity work. I learned Spanish, worked on immigrant rights, became the Midwest Regional Director for a couple years. CISPES was connected to the larger anti-war movement so I also participated in opposing the war in Yugoslavia, and other US interventions in the 1990s.

I learned a lot about how to organize from CISPES. Anyone who worked with them will tell you that. The lessons applied from Salvadoran compañeros proved invaluable for all kinds of organizing.

One person who especially influenced my thinking and practice was Maria Serrano. She spoke at the first convention I attended. People were struggling with what to do next after the end of the Civil War. The debate was: Will people follow us if we do X or Y? Serrano said, “If you are asking this question you are already doing it wrong. You should be so connected to the people you don’t need to ask.” (I knew she was a socialist. I wanted to be that smart. I began to explore socialism. I am still a socialist today.)

The other thing I heard often in El Salvador was: “The people are our mountains.” The Salvadorans were referencing the Vietnamese and Guinea. When I was later targeted by the FBI, I experienced what they meant.

No Grapes

When I first left Macalester, I got a job working for No Grapes Minnesota — getting paid pennies. My job was to convince students groups and trade unions to invite me to talk about the grape boycott. Through that work, I learned about the legacy of farm worker struggles of the 1960s and 70s, and about union organizing. My parents were both trade union members and my first job working at a bowling alley, was union, but this was the beginning of my labor activism.

Around this time, I moved into a house in Minneapolis with fellow activists Steff Yorek, Zeno Wood and J Burger. That was my first activist house. It was a great experience.

Visiting Iraq to Witness the Impact of US Sanctions

My CISPES years ended after I traveled to Iraq in 1998 as part of the Iraq Sanctions Challenge delegation. About 100 people went, bringing material aid in violation of the brutal US/UN sanctions that were creating immense suffering, especially for children. I went with Marie Braun, and a college student from the U of M. It was life changing.

I witnessed the long-term impact of the Persian Gulf War as well as the sanctions. We visited a bomb shelter in Al-A’amiriya, a neighborhood of Baghdad targeted by the US. They dropped two “Smart” bombs, killing those inside. The shelter had been turned into a memorial.

We were hosted by Um-Raida, a woman who had been staying in the shelter, but gone out early in the morning the day the bombs dropped to get food for Eid. Her daughter, Raida, and everyone else who was inside, was killed. (Um-Raida means mother of Raida, and this is why our guide took on this name.)

She shared her horrific story. The bombs burst water pipes. People drowned in boiling water, others burned to death. There was a water line in the basement. Above it you could see hand prints of people who had struggled, and shadows of incinerated bodies on the walls. The walls were lined with photos of the people who died. Most were women and children.

We went to Saddam Children’s Hospital. Before the war, Iraq had an advanced medical system. Due to the sanctions, Iraq couldn’t buy medicine. They had this modern hospital, but no supplies. The pharmacy shelves were empty. People were dying of easily treated diseases, from dysentery due to poisoned water, from malnutrition, and from cancer caused by depleted uranium.

The hospital really got to me. I had spent a lot of time in hospitals. I had never seen a modern facility without medicine. I have complicated health problems, but people in Iraq were dying because they couldn’t get heart medicine or inhalers.

Some people on the trip took pictures of sick children. I got angry. With my background as a person with disabilities, I have acute discomfort with the poster-child thing. They were not asking permission. These were families who were maybe going to lose their children. It felt like a sacred place and a very un-sacred way to be in it. We were there because they did want their stories told, so in a way my fellow travelers weren’t necessarily wrong. The photos they took were a way to bring these Iraqi stories home to the US.

Marie and I met the relatives of an Iraqi immigrant family we knew from home. I remember meeting my friend Layla’s uncle, who was a recently released prisoner of war in Iran. He was thin and quiet, still unhealthy and traumatized. Another Uncle made a meal for us in their home. Their son loved Micheal Jackson. He asked me to moonwalk for him. I did. Most people would say I didn’t, but….I tried.

All the people we met were happy to see us. They would say: “We hate your government, not your people.” That is hard for Americans to do. To instill that outlook in people here, would be life changing. I’ve been working on that ever since.

Getting Married before Gay Marriage

Along the way I got married and had a beautiful child.

Steff grew up in Little Falls. Her family is Catholic, my family is atheist. Both of our families were working class and both our fathers were truck drivers. One of our first dates we saw the movie Convoy at a Minneapolis movies in the parks. We are both members of Freedom Road Socialist Organization. She has always been a huge support, taking care of me when I’m sick — which has happened a lot in our years together.

We decided to marry before it was legal. I wanted to, but Steff wasn’t sure at first. We had to figure out how to do it. We wanted the marriage to be recognized by our families. We wanted our parents to know this was real. We needed a judge or a pastor in a robe. Our first choice was a judge, but we couldn’t find one that would do it. We tried Walker Methodist, but they wouldn’t do it unless we joined the Church.

Tony Machado, pastor from Todos Los Santos, and a political Nuyorican, agreed to marry us. We had the ceremony at the Macalester Chapel, a space in which we had participated in many political events. Steff, and a crew of family and friends, did the cooking. My younger brothers were in the wedding, and both gave speeches, along with a couple friends and Steff’s sister. At our reception, Zeno played “The Internationale” on the trumpet, and all the activists (and my brothers) stood and raised their fists.

We started talking about having children. I really wanted to have a family in that way. Steff was in no hurry, but then the biological clock started ticking. Our former roommate, Zeno, who was now living in New York was our donor. There was no question that Steff would be the one to carry the pregnancy, due to my health problems.

Now we have an awesome kid.

My mom is my best friend. Our relationship stumbled a little when I came out, when I married a woman, and when we had a child…. Mom didn’t have friends with queer children, she didn’t know any queer families with kids. It took her awhile to turn the corner. Now she can’t get enough of her grandchild and she boasts about us. But it was hard at first.

Having a Child Meant Coming Out Again

I wasn’t prepared for it. My queer identity isn’t something I talk about all the time — but I live it. In the early 2000s there was openness about being queer, but still a lot of places where it wasn’t comfortable. I was used to choosing how to be in different situations. It was a safety issue and an economic one, in terms of jobs. But now that we had a kid we didn’t want to be closeted in any places. We didn’t want our child (they/them ze/zir/zem pronouns) to have any shame.

People like to be involved in your life when you have a kid, so everyday we were answering questions. Where is your Dad? Why do you have two moms? Everyday we had to come out to strangers. We still do.

It was different to come out again when we were older and sure of ourselves. Leila helped. To them we were the norm. When they were little they thought everyone had two moms.

Organizing with Clerical Workers

I was a clerical worker at the U of M for about 10 years. During part of that time I served as a board member of the Union —AFSCME 3800. In 2003 and 2007 we went on strike. The first time it was only the clerical workers. The second time we had other AFSCME locals at the U — healthcare and technical workers — striking with us.

U of M clerical workers are 80% women. We struck for higher wages, health care, good benefits. This was a time of austerity at the U and the lowest paid workers were asked to bear the brunt of it. We faced rising healthcare costs, attacks on step increases, a lack of seniority rights. The University didn’t think we’d fight back.

It was tough organizing. Clerical work is a helping profession. We cared about the students and faculty we served, and we identified with our departments. It was a challenge to unite and stand up for ourselves, but when we did we had incredible support from the community. I helped lead our strike support committees — with faculty, students, churches, and other unions.

You don’t strike for fast money. You strike for the long-term strength of your union, for dignity, and for the wellbeing of workers in years to come. I worked on the committee that distributed hardship funds. People had risked a lot. You learn about working class solidarity. We learned that from each other.

Unions have been in decline for a long time, but they are thrusting back. We have to. Unions are all working people have. We made real gains through those strikes. We slowed the rising costs of healthcare, and protected guarantees for future raises (keeping step increases in our contract). We also strengthened our union power, putting us in the position to eventually win the parental leave benefits faculty had. Because of our work, U clerical workers already have a $15 minimum.

Being Raided by the FBI

As part of my work with the Anti-war Committee (an organization I co-founded after returning from Iraq), we engaged in solidarity. We hosted speakers and traveled to places where the United States was intervening. When the bad guys came to town, we protested.

We viewed the election of 2008 as a referendum on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Republican National Convention in St Paul in 2008 became a focus. The Twin Cities organized a week of activities including huge protests and mass civil disobedience actions. Unbeknownst to us, a dirty rotten spy got herself arrested with us at the RNC and afterward joined the Anti-War Committee.

“Karen Sullivan.” She was awkward, but many activists are. I remember wondering if she was all right. The Anti-War Committee had a familial culture, supporting each other, taking care of each other’s babies. She joined that familial circle. All the while she was reporting to the government about us, especially our interest in Palestine and Colombia.

2010 was an intense year. There was that massive earthquake in Haiti in January. My grandfather died. In April, I had a brain hemorrhage, which I’m lucky to have survived. Half of people who experience it die, half of survivors are severely and permanently disabled. After weeks of recovery and rehab, I attempted to return to work, but in the end, I needed to quit my clerical job and apply for disability. Just after I stopped working, my grandmother died too.

I was still recovering physically, and grieving for my grandparents, when the FBI invaded my home at 7am on September 24, 2010.

I live in the diverse Phillips neighborhood of Minneapolis. In September of 2010, when the FBI raided our home, the activist community showed up on our lawn to show their support. I was in bed. Steff and Leila — who was in first grade —were up. The FBI had a search warrant. They asked if we wanted to talk to them about “material support to foreign terrorists.” We did not agree to speak with them. (No one should ever talk to the FBI, and certainly not without the presence of a lawyer.) They seized our phones, computers, papers, pictures of Colombia and Palestine, anything with Spanish or Arabic writing. They took my passport.

I insisted on calling my attorney. Bruce Nestor was in New Orleans at the national meeting for the National Lawyers Guild. I asked whether it was okay to talk to media or speak publicly about the raids, and he simply said not to say anything you hadn’t already said publicly.

That was easy. Everything we did was public.

Some of what happened that day is a blur. I know Garrett Fitzgerald knocked on the door and told FBI agents he was Leila’s childcare provider. He sat with her outside for hours while the FBI was inside.What I do remember clearly is the people. They came. They gathered on the lawn. They said, “This is ridiculous. We know these people. They are protesters, not terrorists. We stand with them.” The people were our mountains.

We soon learned that people from across the country who helped build the 2008 RNC protests were also visited. Some 72 FBI agents carried out a coordinated attack on our movement that morning.

We did a number things quickly. We all knew we would refuse to testify before a grand jury. We built a national network to organize our public defense — the Committee to Stop FBI Repression. As individuals, we made arrangements for who would care for our kids if we went to jail. We thought about how to make sure they would have enough money to care for the children without our wages. Then we waited to see what the government would do.

As often happens, they investigated people around us. Carlos Montes, a veteran activist since the 1960s — leader of the Chicano movement in California — was arrested. About two years later they arrested a Palestinian woman working and living in Chicago. We fought to defend her, but in 2017 she was deported. It has been hard to deal with the fact that choices I made led to other people getting caught in the government’s drag net.

Activism I did after the raids focused on support for her and for all political prisoners, people involved in Puerto Rican liberation, Black Liberation movements — people in prison for decades.

Community Control of the Police

When Jamar Clark was killed in Minneapolis I knew I wanted to participate in that movement. I joined the Twin Cities Coalition for Justice for Jamar as it came together during the 4th precinct occupation in November, 2015. When the occupation was forcibly shut down by the City, we chose to continue the work to demand that killer cops be prosecuted in open court.

I learned from my experience with the FBI about the injustice of secret Grand Juries. We protested every Friday at Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman’s office until he announced there would be no Grand Jury. We also wanted to provide solidarity for families of those who’ve been killed. Their leadership and voices needs to be central. They didn’t choose this work, it chose them.

Organizers have something to offer. People in communities of color have always known the police lie. We helped the broader community learn that lesson. Like the lie Mike Freeman told about Jamar being involved in domestic violence. That didn’t happen. Two dozen black witnesses said that Jamar was unjustly killed, but Freeman deemed them all not believable.

Local work is different from struggling against war, which often feels like tilting at windmills. There is a possibility that our demands will be addressed.

There have been several more police killings since then. Since the movement stood up for Jamar, the way these cases have been dealt with has changed. Right now we are advocating for community control of the police. What does that mean?

- We need an all-civilian council overseeing the police. Right now it’s just the Mayor. Under this system the police union has more power than their bosses! Violent cops with multiple complaints stay on the street and receive no disciplinary action. We need a civilian council that is independent and has power. A council with no cops or family of cops.

- This civilian council would set the rules of conduct. So they could, for example, outlaw the chokehold that led to Jamar’s murder. Police involved in shootings could be removed immediately, without the pay they get now. The council would have the power to fire and discipline cops.

- The Civilian council would control the budget. Right now the cops control the budget. Some neighborhoods are over-policed. The civilian board could decide what are policing priorities.

Some people advocate for abolition of the police. I think that’s a distant goal. Today we need to demand democratic control over how the police force is run. We want to see the power in the hands of Black, Brown and Indigenous folks.

Community members know what justice looks like.